Jennifer Krasinski at Artforum:

SINCE 2006, Kelly Copper and Pavol Liška, collaborating as the Nature Theater of Oklahoma, have created brainy and ebullient works for stage, film, and video, aerating serious conceptual heft with an oddball comedic sensibility. For the directing-and-writing duo, scripts have never been hard-and-fast things. Take the one for their epic nine-part video Life and Times (2009–15): The words were transcribed from phone conversations between Liška and company member Kristin Worrall, during which the latter recounted the (often banal) details of her life thus far. What else would one expect from a team whose moniker is lifted from a poster that appears in Franz Kafka’s Amerika (1927) announcing an opportunity to join the Nature Theater of Oklahoma: “Anyone who wants to become an artist should contact us! We are a theater that can make use of everyone, each in his place!”

SINCE 2006, Kelly Copper and Pavol Liška, collaborating as the Nature Theater of Oklahoma, have created brainy and ebullient works for stage, film, and video, aerating serious conceptual heft with an oddball comedic sensibility. For the directing-and-writing duo, scripts have never been hard-and-fast things. Take the one for their epic nine-part video Life and Times (2009–15): The words were transcribed from phone conversations between Liška and company member Kristin Worrall, during which the latter recounted the (often banal) details of her life thus far. What else would one expect from a team whose moniker is lifted from a poster that appears in Franz Kafka’s Amerika (1927) announcing an opportunity to join the Nature Theater of Oklahoma: “Anyone who wants to become an artist should contact us! We are a theater that can make use of everyone, each in his place!”

Their latest triumph is a film adaptation of Austrian Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek’s 666-page novel Die Kinder der Toten (The Children of the Dead, 1995)—by the writer’s own estimation, her masterwork. A lashing of Austrian “forgetfulness” regarding the Holocaust and its lethal legacy, hers is a disaster traumedy in which the dead return to a quiet Austrian town as zombies, only to die and return again and again.

more here.

“In the short term, it would be very positive for the housing market,” says Lawrence Yun, the National Association of Realtors chief economist. He says his group’s

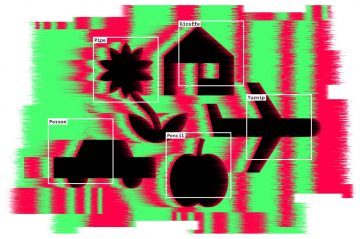

“In the short term, it would be very positive for the housing market,” says Lawrence Yun, the National Association of Realtors chief economist. He says his group’s  A self-driving car approaches a stop sign, but instead of slowing down, it accelerates into the busy intersection. An accident report later reveals that four small rectangles had been stuck to the face of the sign. These fooled the car’s onboard artificial intelligence (AI) into misreading the word ‘stop’ as ‘speed limit 45’.

A self-driving car approaches a stop sign, but instead of slowing down, it accelerates into the busy intersection. An accident report later reveals that four small rectangles had been stuck to the face of the sign. These fooled the car’s onboard artificial intelligence (AI) into misreading the word ‘stop’ as ‘speed limit 45’. Wall Street

Wall Street  Whether or not she believes them, Chu’s initial theses lead her into a series of chapters in which she theorizes, among other things, gender transition according to the recuperated principles of her personally curated second-wave feminism. Chu quotes her icon Solanas on Candy Darling (1944–1974), an actor and trans woman associated with Warhol’s Factory scene: “[A] perfect victim of male suppression.” (Chu says the epithet was spoken “admiringly”; it’s hard to see how.) Females inclines toward this view, with a twist. Trans women come across as the dupes of patriarchal gender norms, consuming and reproducing the stereotyped and anti-feminist images of the beauty industry. In that mode, Chu describes the YouTube makeup artist Gigi Gorgeous as “in the most technical sense of this phrase, a dumb blonde.” She only recuperates this, frankly, sexist jeer by universalizing its principle: “From the perspective of gender, then, we’re all dumb blondes.” Trading on an alt-right lexicon borrowed from The Matrix, she refers to hormone therapy as “plugging […] back into the simulation.” The charge that gender transition reinforces sexist stereotypes and retrograde gender norms is an old accusation; it doesn’t get more convincing when the person saying it happens to be trans herself. Chu updates this anti-trans feminism by generalizing its theses: she agrees with the accusation that transition sustains the objectification of women, and submits that there’s no way out, for trans people or anybody else.

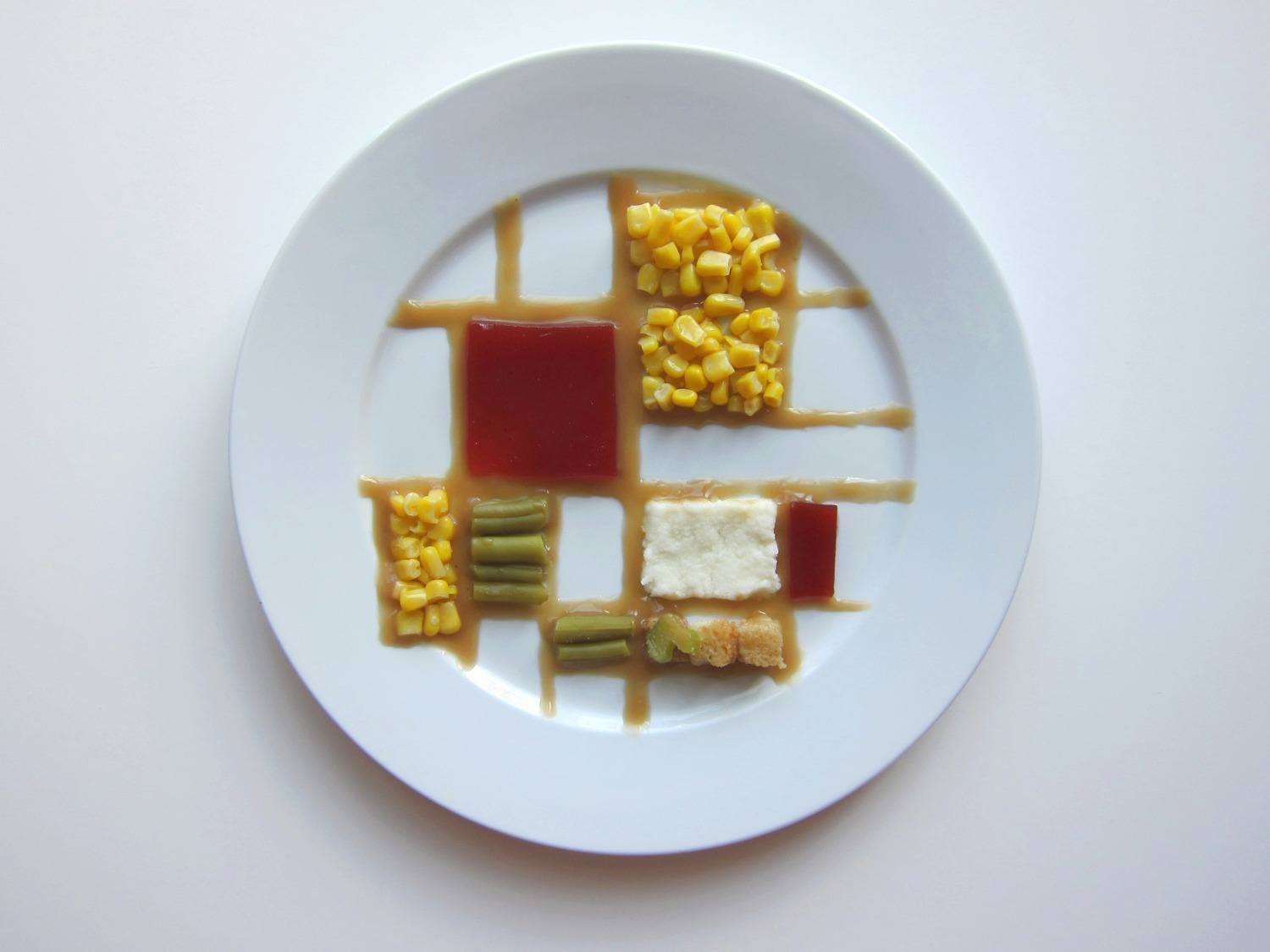

Whether or not she believes them, Chu’s initial theses lead her into a series of chapters in which she theorizes, among other things, gender transition according to the recuperated principles of her personally curated second-wave feminism. Chu quotes her icon Solanas on Candy Darling (1944–1974), an actor and trans woman associated with Warhol’s Factory scene: “[A] perfect victim of male suppression.” (Chu says the epithet was spoken “admiringly”; it’s hard to see how.) Females inclines toward this view, with a twist. Trans women come across as the dupes of patriarchal gender norms, consuming and reproducing the stereotyped and anti-feminist images of the beauty industry. In that mode, Chu describes the YouTube makeup artist Gigi Gorgeous as “in the most technical sense of this phrase, a dumb blonde.” She only recuperates this, frankly, sexist jeer by universalizing its principle: “From the perspective of gender, then, we’re all dumb blondes.” Trading on an alt-right lexicon borrowed from The Matrix, she refers to hormone therapy as “plugging […] back into the simulation.” The charge that gender transition reinforces sexist stereotypes and retrograde gender norms is an old accusation; it doesn’t get more convincing when the person saying it happens to be trans herself. Chu updates this anti-trans feminism by generalizing its theses: she agrees with the accusation that transition sustains the objectification of women, and submits that there’s no way out, for trans people or anybody else. Lucy Ellmann’s new novel, Ducks, Newburyport, does not, despite the claims of some reviewers, consist of a single sentence (I counted 880). But it does contain one very long one: a comma-strewn stream that follows the thoughts of an Ohioan housewife during the first few months of 2017. While she bakes the pies she sells to local diners she worries about her four children, considers language usage (the difference between ‘envy’ and ‘jealousy’ and ‘affect’ and ‘effect’; the misuse of ‘enormity’), thinks lovingly about her husband, Leo, mourns her dead parents, and despairs over the state of the environment, Trump’s presidency, mass shootings, and the historic genocides of indigenous people. ‘A lot of people think all I think about is pie,’ she thinks, ‘when really it’s my spinal brain doing most of the peeling and caramelising and baking and flipping, while I just stand there spiralling into a panic about my mom and animal extinctions and the Second Amendment just like everybody else.’

Lucy Ellmann’s new novel, Ducks, Newburyport, does not, despite the claims of some reviewers, consist of a single sentence (I counted 880). But it does contain one very long one: a comma-strewn stream that follows the thoughts of an Ohioan housewife during the first few months of 2017. While she bakes the pies she sells to local diners she worries about her four children, considers language usage (the difference between ‘envy’ and ‘jealousy’ and ‘affect’ and ‘effect’; the misuse of ‘enormity’), thinks lovingly about her husband, Leo, mourns her dead parents, and despairs over the state of the environment, Trump’s presidency, mass shootings, and the historic genocides of indigenous people. ‘A lot of people think all I think about is pie,’ she thinks, ‘when really it’s my spinal brain doing most of the peeling and caramelising and baking and flipping, while I just stand there spiralling into a panic about my mom and animal extinctions and the Second Amendment just like everybody else.’ Everyone wants to know how this is going to end, but no one has an answer. I know this: We are going to be living with the consequences of trauma for years. They can scrub the walls clean of the graffiti, but the horrific images will continue to eat away at us: a protester shot at point-blank range; a tear-gas canister erupting onto someone’s back, burning the flesh blue-black; a man pressed to the ground, bleeding profusely and teeth knocked out; a pair of punctured eye goggles. The trials for those who participated in the 79-day Umbrella Movement in 2014 have only just ended. We will spend the next couple of years watching the government throw hundreds, if not thousands, in jail.

Everyone wants to know how this is going to end, but no one has an answer. I know this: We are going to be living with the consequences of trauma for years. They can scrub the walls clean of the graffiti, but the horrific images will continue to eat away at us: a protester shot at point-blank range; a tear-gas canister erupting onto someone’s back, burning the flesh blue-black; a man pressed to the ground, bleeding profusely and teeth knocked out; a pair of punctured eye goggles. The trials for those who participated in the 79-day Umbrella Movement in 2014 have only just ended. We will spend the next couple of years watching the government throw hundreds, if not thousands, in jail. On Aug. 15, 1914, a servant set fire to Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s sprawling estate in Spring Green, Wis. Julian Carlton also took up an ax and murdered seven people, among them Wright’s mistress, Mamah Cheney, and her two children. Wright was already famous, as this country’s preeminent architect, and notorious, for leaving his wife and children for Cheney, with whom he lived openly and, by contemporary standards, shamelessly. The massacre made headlines around the country, and though Carlton’s motives remain obscure and unknowable to this day, the carnage was held up by many as divine retribution for Wright’s marital misbehavior.

On Aug. 15, 1914, a servant set fire to Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s sprawling estate in Spring Green, Wis. Julian Carlton also took up an ax and murdered seven people, among them Wright’s mistress, Mamah Cheney, and her two children. Wright was already famous, as this country’s preeminent architect, and notorious, for leaving his wife and children for Cheney, with whom he lived openly and, by contemporary standards, shamelessly. The massacre made headlines around the country, and though Carlton’s motives remain obscure and unknowable to this day, the carnage was held up by many as divine retribution for Wright’s marital misbehavior. In one important way, the recipient of a heart transplant ignores its new organ: Its nervous system usually doesn’t rewire to communicate with it. The 40,000 neurons controlling a heart operate so perfectly, and are so self-contained, that a heart can be cut out of one body, placed into another, and continue to function perfectly, even in the absence of external control, for a decade or more. This seems necessary: The parts of our nervous system managing our most essential functions behave like a Swiss watch, precisely timed and impervious to perturbations. Chaotic behavior has been throttled out.

In one important way, the recipient of a heart transplant ignores its new organ: Its nervous system usually doesn’t rewire to communicate with it. The 40,000 neurons controlling a heart operate so perfectly, and are so self-contained, that a heart can be cut out of one body, placed into another, and continue to function perfectly, even in the absence of external control, for a decade or more. This seems necessary: The parts of our nervous system managing our most essential functions behave like a Swiss watch, precisely timed and impervious to perturbations. Chaotic behavior has been throttled out. The so-called Muscovy duck is so called not in view of its homeland in the vicinity of Moscow –for in fact it is native to Central and South America– but rather in mistranslation of its Latin designation, Anas moschata, the “musky duck”, thus “not transferred from Muscovia,” as the English naturalist John Ray writes in 1713, “but from the rather strong musk odour it exudes.”

The so-called Muscovy duck is so called not in view of its homeland in the vicinity of Moscow –for in fact it is native to Central and South America– but rather in mistranslation of its Latin designation, Anas moschata, the “musky duck”, thus “not transferred from Muscovia,” as the English naturalist John Ray writes in 1713, “but from the rather strong musk odour it exudes.”

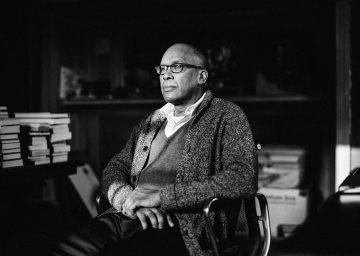

An infinite number of things happen; we bring structure and meaning to the world by making art and telling stories about it. Every work of literature created by human beings comes out of an historical and cultural context, and drawing connections between art and its context can be illuminating for both. Today’s guest, Stephen Greenblatt, is one of the world’s most celebrated literary scholars, famous for helping to establish the New Historicism school of criticism, which he also refers to as “cultural poetics.” We talk about how art becomes entangled with the politics of its day, and how we can learn about ourselves and other cultures by engaging with stories and their milieu.

An infinite number of things happen; we bring structure and meaning to the world by making art and telling stories about it. Every work of literature created by human beings comes out of an historical and cultural context, and drawing connections between art and its context can be illuminating for both. Today’s guest, Stephen Greenblatt, is one of the world’s most celebrated literary scholars, famous for helping to establish the New Historicism school of criticism, which he also refers to as “cultural poetics.” We talk about how art becomes entangled with the politics of its day, and how we can learn about ourselves and other cultures by engaging with stories and their milieu. We are being told of the evils of “cancel culture,” a new scourge that enforces purity, banishes dissent and squelches sober and reasoned debate. But cancel culture is not new. A brief accounting of the illustrious and venerable ranks of blocked and dragged Americans encompasses Sarah Good, Elijah Lovejoy, Ida B. Wells, Dalton Trumbo, Paul Robeson and the Dixie Chicks. What was the Compromise of 1877, which ended Reconstruction, but the cancellation of the black South? What were the detention camps during World War II but the racist muting of Japanese-Americans and their basic rights?

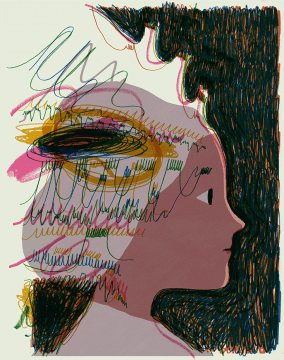

We are being told of the evils of “cancel culture,” a new scourge that enforces purity, banishes dissent and squelches sober and reasoned debate. But cancel culture is not new. A brief accounting of the illustrious and venerable ranks of blocked and dragged Americans encompasses Sarah Good, Elijah Lovejoy, Ida B. Wells, Dalton Trumbo, Paul Robeson and the Dixie Chicks. What was the Compromise of 1877, which ended Reconstruction, but the cancellation of the black South? What were the detention camps during World War II but the racist muting of Japanese-Americans and their basic rights? The male glance is how comedies about women become chick flicks. It’s how discussions of serious movies with female protagonists consign them to the unappealing stable of “strong female characters.” It’s how soap operas and reality television become synonymous with trash. It tricks us into pronouncing mothers intrinsically boring, and it quietly convinces us that female friendships come in two strains: conventional jealousy or the even less appealing non-plot of saccharine love. The third narrative possibility, frenemy-cum-friend, is an only slightly less shallow conversion myth. Who consumes these stories? Who could want to?

The male glance is how comedies about women become chick flicks. It’s how discussions of serious movies with female protagonists consign them to the unappealing stable of “strong female characters.” It’s how soap operas and reality television become synonymous with trash. It tricks us into pronouncing mothers intrinsically boring, and it quietly convinces us that female friendships come in two strains: conventional jealousy or the even less appealing non-plot of saccharine love. The third narrative possibility, frenemy-cum-friend, is an only slightly less shallow conversion myth. Who consumes these stories? Who could want to? A

A Pinckney’s emphasis on the interpolation of class and race can make him appear closer to the leftist Afro-Caribbean tradition of race theorists—exemplified by thinkers such as Paul Gilroy and Stuart Hall—who reject mythical or essentialist theories of racism in favor of a concrete economic analysis, in which racial distinctions have been created and maintained primarily for the sake of capitalist exploitation. For Pinckney, blackness is not an essential quality found in the blood, the spirit, or even the genes (“I’d never liked that way of assigning innate behavioral characteristics to whole nations or groups. The work of every serious social scientist militated against it.”) but a conceptual framework subject to history, like everything else. “The Irish used to be black socially, meaning at the bottom,” he writes in one example. “The gift of being white helped to subdue class antagonism.”

Pinckney’s emphasis on the interpolation of class and race can make him appear closer to the leftist Afro-Caribbean tradition of race theorists—exemplified by thinkers such as Paul Gilroy and Stuart Hall—who reject mythical or essentialist theories of racism in favor of a concrete economic analysis, in which racial distinctions have been created and maintained primarily for the sake of capitalist exploitation. For Pinckney, blackness is not an essential quality found in the blood, the spirit, or even the genes (“I’d never liked that way of assigning innate behavioral characteristics to whole nations or groups. The work of every serious social scientist militated against it.”) but a conceptual framework subject to history, like everything else. “The Irish used to be black socially, meaning at the bottom,” he writes in one example. “The gift of being white helped to subdue class antagonism.”