Richard Marshall in 3:16 AM:

Jeremy Avigad is a professor in the Department of Philosophy and the Department of Mathematical Sciences and associated with Carnegie Mellon’s interdisciplinary program in Pure and Applied Logic. He is interested in mathematical logic and proof theory, formal verification and automated reasoning and the history and philosophy of mathematics. Here he discusses the relationship between philosophy and mathematics, philosophy of mathematics and analytic philosophy, early twentieth century mathematical innovation, Hilbert and Henri Poincare, mathematical logic, the distinction between syntax and semantics, about not being dogmatic about foundations, change in mathematics, the role of computers in mathematical enquiry, the modularity of mathematics, whether mathematics is discovered or designed, why David Hilbert is important, and formal verification, automated reasoning and AI.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Jeremy Avigad: My graduate degree is in mathematics, specifically in logic, but I have been thinking about mathematics for almost as long as I have been doing it. It was Carnegie Mellon that turned philosophy into a profession for me. I am eternally grateful to my department for recognizing that the foundational work I was trained to do is philosophically important, and for giving me room to use that background to explore the history and philosophy of mathematics.

More here.

It is indeed supremely difficult to effectively refute the claim that John von Neumann is likely the most intelligent person who has ever lived. By the time of his death in 1957 at the modest age of 53, the Hungarian polymath had not only revolutionized several subfields of mathematics and physics but also made foundational contributions to pure economics and statistics and taken key parts in the invention of the atomic bomb, nuclear energy and digital computing.

It is indeed supremely difficult to effectively refute the claim that John von Neumann is likely the most intelligent person who has ever lived. By the time of his death in 1957 at the modest age of 53, the Hungarian polymath had not only revolutionized several subfields of mathematics and physics but also made foundational contributions to pure economics and statistics and taken key parts in the invention of the atomic bomb, nuclear energy and digital computing. After the 2008 election, the New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza reported that Obama had told his incoming political director, Patrick Gaspard, “I think that I’m a better speechwriter than my speechwriters. I know more about policies on any particular issue than my policy directors. And I’ll tell you right now that I’m going to think I’m a better political director than my political director.”

After the 2008 election, the New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza reported that Obama had told his incoming political director, Patrick Gaspard, “I think that I’m a better speechwriter than my speechwriters. I know more about policies on any particular issue than my policy directors. And I’ll tell you right now that I’m going to think I’m a better political director than my political director.” President Trump has far surpassed Nixon in his zeal to ignore, jettison or rewrite the nation’s norms. Even his allies in the Republican Party, in which Trump still has

President Trump has far surpassed Nixon in his zeal to ignore, jettison or rewrite the nation’s norms. Even his allies in the Republican Party, in which Trump still has  The hero of Thomas Hardy’s tragic novel Jude the Obscure (1895) is a poor stonemason living in a Victorian village who is desperate to study Latin and Greek at university. He gazes, from the top of a ladder leaning against a rural barn, on the spires of the University of Christminster (a fictional substitute for Oxford). The spires, vanes and domes ‘like the topaz gleamed’ in the distance. The lustrous topaz shares its golden colour with the stone used to build Oxbridge colleges, but it is also one of the hardest minerals in nature. Jude’s fragile psyche and health inevitably collapse when he discovers just how unbreakable are the social barriers that exclude him from elite culture and perpetuate his class position, however lovely the buildings seem that concretely represent them, shimmering on the horizon. By Hardy’s time, the trope of the exclusion of the working class from the classical cultural realm, especially from access to the ancient languages, had become a standard feature of British fiction. Charles Dickens probes the class system with a tragicomic scalpel in David Copperfield (1850). The envious Uriah sees David as a privileged young snob, but he refuses to accept the offer of Latin lessons because he is ‘far too umble. There are people enough to tread upon me in my lowly state, without my doing outrage to their feelings by possessing learning.’

The hero of Thomas Hardy’s tragic novel Jude the Obscure (1895) is a poor stonemason living in a Victorian village who is desperate to study Latin and Greek at university. He gazes, from the top of a ladder leaning against a rural barn, on the spires of the University of Christminster (a fictional substitute for Oxford). The spires, vanes and domes ‘like the topaz gleamed’ in the distance. The lustrous topaz shares its golden colour with the stone used to build Oxbridge colleges, but it is also one of the hardest minerals in nature. Jude’s fragile psyche and health inevitably collapse when he discovers just how unbreakable are the social barriers that exclude him from elite culture and perpetuate his class position, however lovely the buildings seem that concretely represent them, shimmering on the horizon. By Hardy’s time, the trope of the exclusion of the working class from the classical cultural realm, especially from access to the ancient languages, had become a standard feature of British fiction. Charles Dickens probes the class system with a tragicomic scalpel in David Copperfield (1850). The envious Uriah sees David as a privileged young snob, but he refuses to accept the offer of Latin lessons because he is ‘far too umble. There are people enough to tread upon me in my lowly state, without my doing outrage to their feelings by possessing learning.’ Democracy depends

Democracy depends Jedediah Britton-Purdy in New Republic:

Jedediah Britton-Purdy in New Republic: Erica Chenoweth, Sirianne Dahlum, Sooyeon Kang, Zoe Marks, Christopher Wiley Shay and Tore Wig in The Washington Post:

Erica Chenoweth, Sirianne Dahlum, Sooyeon Kang, Zoe Marks, Christopher Wiley Shay and Tore Wig in The Washington Post: Adam Tooze in Social Europe:

Adam Tooze in Social Europe: Jay Caspian Kang in The New Yorker:

Jay Caspian Kang in The New Yorker: How did the most successful conservative party of the 20th century become the agent for a national humiliation? How could a political party so firmly tied to power, not least economic power, come to disregard its own particular view of the national interest? The Conservative-born Brexit crisis that has tormented the nation since 2016 has multiple causes, the most crucial and under-explored of which is economic. The great financial crisis of 2008 certainly had an impact on the referendum result: it led to economic stagnation, not least in productivity and wages, as well as disastrous cuts to many public services. Local authorities, responsible for social care, were hit especially hard, as were the working poor. But the really significant economic transformations behind the decision to leave the EU have deeper roots. Over the past 40 years the nature of capitalism in the UK has changed in ways that concepts such as “neoliberalism” and “post-industrialism” have failed to grasp. The relationship between capitalism and politics has also changed radically.

How did the most successful conservative party of the 20th century become the agent for a national humiliation? How could a political party so firmly tied to power, not least economic power, come to disregard its own particular view of the national interest? The Conservative-born Brexit crisis that has tormented the nation since 2016 has multiple causes, the most crucial and under-explored of which is economic. The great financial crisis of 2008 certainly had an impact on the referendum result: it led to economic stagnation, not least in productivity and wages, as well as disastrous cuts to many public services. Local authorities, responsible for social care, were hit especially hard, as were the working poor. But the really significant economic transformations behind the decision to leave the EU have deeper roots. Over the past 40 years the nature of capitalism in the UK has changed in ways that concepts such as “neoliberalism” and “post-industrialism” have failed to grasp. The relationship between capitalism and politics has also changed radically.

J. M. Coetzee (JMC): Balzac famously wrote that behind every great fortune lies a crime. One might similarly claim that behind every successful colonial venture lies a crime, a crime of dispossession. Just as in the dynastic novels of the nineteenth century the heirs of great fortunes are haunted by the crimes on which their fortunes were founded, a successful colony like Australia seems to be haunted by a history that will not go away. The question of what to say or do about dispossession of Indigenous Australians is as alive in the Australian imagination as it has ever been.

J. M. Coetzee (JMC): Balzac famously wrote that behind every great fortune lies a crime. One might similarly claim that behind every successful colonial venture lies a crime, a crime of dispossession. Just as in the dynastic novels of the nineteenth century the heirs of great fortunes are haunted by the crimes on which their fortunes were founded, a successful colony like Australia seems to be haunted by a history that will not go away. The question of what to say or do about dispossession of Indigenous Australians is as alive in the Australian imagination as it has ever been. Bowie was a famously insatiable reader. As a teenager in Bromley he was schooled in the Beats by his older brother Terry. Cocaine-crazed in 1970s America, he would stay up all night inhaling books about the occult from his 1,500-volume portable library. In 1998, somewhat more well adjusted, he wrote reviews for Barnes & Noble. Feeling from an early age formless and incomplete, he rebuilt himself from pieces of the things he loved: not just literature and music but cinema, art, people, places. While the similarly well-read Bob Dylan preferred to veil his sources, Bowie made an exhibition of them – literally so at his touring museum show David Bowie Is, where some of his favourite books dangled from the ceiling like mobiles. He was the star-as-fan and his fandom was promiscuous. When LCD Soundsystem’s

Bowie was a famously insatiable reader. As a teenager in Bromley he was schooled in the Beats by his older brother Terry. Cocaine-crazed in 1970s America, he would stay up all night inhaling books about the occult from his 1,500-volume portable library. In 1998, somewhat more well adjusted, he wrote reviews for Barnes & Noble. Feeling from an early age formless and incomplete, he rebuilt himself from pieces of the things he loved: not just literature and music but cinema, art, people, places. While the similarly well-read Bob Dylan preferred to veil his sources, Bowie made an exhibition of them – literally so at his touring museum show David Bowie Is, where some of his favourite books dangled from the ceiling like mobiles. He was the star-as-fan and his fandom was promiscuous. When LCD Soundsystem’s  In 1965, the year of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches and the Watts riots, an ancillary skirmish played out across the Atlantic. James Baldwin, then at the height of his international reputation, faced off against William F. Buckley Jr., the “keeper of the tablets” of American conservatism, in the genteel confines of the Cambridge Union. The proposition before the house was: “The American dream is at the expense of the American Negro.” For Baldwin, who would roll his eyes more than once during the debate, the question indicated glaring ignorance. The American dream was a nightmare from which he was trying to wake. For Buckley, the American dream was a giant bootstrap that American blacks refused to employ. “We will fight … on the beaches and on the hills, and on mountains and on landing grounds,” he told the audience of students that evening, channeling Winston Churchill. Only Buckley invoked the imagery of plucky guerrilla resistance not against a Nazi invasion of the British Isles, but against Northern radicals bent on uprooting the Southern way of life.

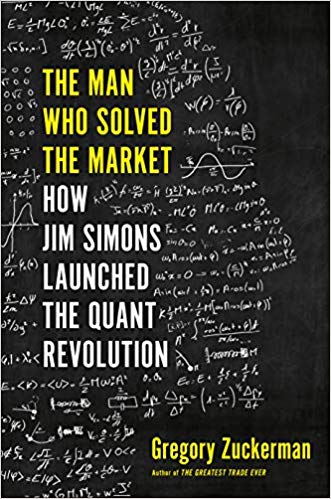

In 1965, the year of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches and the Watts riots, an ancillary skirmish played out across the Atlantic. James Baldwin, then at the height of his international reputation, faced off against William F. Buckley Jr., the “keeper of the tablets” of American conservatism, in the genteel confines of the Cambridge Union. The proposition before the house was: “The American dream is at the expense of the American Negro.” For Baldwin, who would roll his eyes more than once during the debate, the question indicated glaring ignorance. The American dream was a nightmare from which he was trying to wake. For Buckley, the American dream was a giant bootstrap that American blacks refused to employ. “We will fight … on the beaches and on the hills, and on mountains and on landing grounds,” he told the audience of students that evening, channeling Winston Churchill. Only Buckley invoked the imagery of plucky guerrilla resistance not against a Nazi invasion of the British Isles, but against Northern radicals bent on uprooting the Southern way of life. There’s an excellent new book out about Jim Simons and Renaissance Technologies,

There’s an excellent new book out about Jim Simons and Renaissance Technologies,  The elderly

The elderly