Jessica Weisberg in The New Yorker:

Commercial surrogacy, the practice of paying a woman to carry and birth a child whom she will not parent, is largely unregulated in America. It’s illegal, with rare exceptions, in three states: New York, Louisiana, and Michigan. But, most states have no surrogacy laws at all. Though the technology was invented in 1986, the concept still seems, for many, a bit sci-fi, and support for it does not follow obvious political fault lines. It is typically championed by the gay-rights community, who see it as the only reproductive technology that allows gay men to have biological children, and condemned by some feminists, who see it as yet another business that exploits the female body. In June, when the New York State Assembly considered a bill that would legalize paid surrogacy, Gloria Steinem vigorously opposed it. “Under this bill, women in economic need become commercialized vessels for rent, and the fetuses they carry become the property of others,” Steinem wrote in a statement.

Commercial surrogacy, the practice of paying a woman to carry and birth a child whom she will not parent, is largely unregulated in America. It’s illegal, with rare exceptions, in three states: New York, Louisiana, and Michigan. But, most states have no surrogacy laws at all. Though the technology was invented in 1986, the concept still seems, for many, a bit sci-fi, and support for it does not follow obvious political fault lines. It is typically championed by the gay-rights community, who see it as the only reproductive technology that allows gay men to have biological children, and condemned by some feminists, who see it as yet another business that exploits the female body. In June, when the New York State Assembly considered a bill that would legalize paid surrogacy, Gloria Steinem vigorously opposed it. “Under this bill, women in economic need become commercialized vessels for rent, and the fetuses they carry become the property of others,” Steinem wrote in a statement.

In a new book, “Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against the Family,” the author Sophie Lewis makes a forceful argument for legalization. Lewis takes little interest in the parents. It’s the surrogates who concern her. Regulation, she says, is the only way for them to avoid exploitation. Lewis frequently, if reluctantly, compares surrogacy to sex work, another industry that persists despite being illegal. Banning these jobs is pointless, Lewis says, aside from giving privileged feminists something to do, and making the work more dangerous. “Surrogacy bans uproot, isolate, and criminalize gestational workers, driving them underground and often into foreign lands, where they risk prosecution,” she writes. “As with sex work, the question of being for or against surrogacy is largely irrelevant. The question is, why is it assumed that one should be more against surrogacy than other risky jobs.”

Lewis does not offer straightforward policy suggestions. Her approach to the material is theoretical, devious, a mix of manifesto and memoir. Early in the book, she struggles to understand why anyone would want to get pregnant in the first place, and later she questions whether continuing the human race is a good idea. But she is solemn and unsparing in her assessment of the status quo. A portion of the book studies the Akanksha Fertility Clinic, in India, a surrogacy center that, according to Lewis, severely underpays and mistreats its workers. (Nayana Patel, who runs the clinic, has argued that Akanksha pays surrogates more than they would make at other jobs.) All of the Akanksha surrogates are required to have children of their own already, ostensibly because they know how difficult it is to raise a child and are therefore less likely to want to keep the ones they’re carrying.

More here.

It is often claimed that the United States differs from Europe in that it lacks a socialist tradition. The title question of Werner Sombart’s 1906 book Why Is There No Socialism in the United States? was answered nearly a century later by Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Wolfe Marks’ It Didn’t Happen Here: Why

It is often claimed that the United States differs from Europe in that it lacks a socialist tradition. The title question of Werner Sombart’s 1906 book Why Is There No Socialism in the United States? was answered nearly a century later by Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Wolfe Marks’ It Didn’t Happen Here: Why  In the summer of

In the summer of Anyone who doubts that genes can specify identity might well have arrived from another planet and failed to notice that the humans come in two fundamental variants: male and female. Cultural critics, queer theorists, fashion photographers, and Lady Gaga have reminded us— accurately—that these categories are not as fundamental as they might seem, and that unsettling ambiguities frequently lurk in their borderlands. But it is hard to dispute three essential facts: that males and females are anatomically and physiologically different; that these anatomical and physiological differences are specified by genes; and that these differences, interposed against cultural and social constructions of the self, have a potent influence on specifying our identities as individuals. That genes have anything to do with the determination of sex, gender, and gender identity is a relatively new idea in our history. The distinction between the three words is relevant to this discussion. By sex, I mean the anatomic and physiological aspects of male versus female bodies. By gender, I am referring to a more complex idea: the psychic, social, and cultural roles that an individual assumes. By gender identity, I mean an individual’s sense of self (as female versus male, as neither, or as something in between).

Anyone who doubts that genes can specify identity might well have arrived from another planet and failed to notice that the humans come in two fundamental variants: male and female. Cultural critics, queer theorists, fashion photographers, and Lady Gaga have reminded us— accurately—that these categories are not as fundamental as they might seem, and that unsettling ambiguities frequently lurk in their borderlands. But it is hard to dispute three essential facts: that males and females are anatomically and physiologically different; that these anatomical and physiological differences are specified by genes; and that these differences, interposed against cultural and social constructions of the self, have a potent influence on specifying our identities as individuals. That genes have anything to do with the determination of sex, gender, and gender identity is a relatively new idea in our history. The distinction between the three words is relevant to this discussion. By sex, I mean the anatomic and physiological aspects of male versus female bodies. By gender, I am referring to a more complex idea: the psychic, social, and cultural roles that an individual assumes. By gender identity, I mean an individual’s sense of self (as female versus male, as neither, or as something in between).

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (1892-1964) is today best remembered as one of the founders of population genetics, which married Charles Darwin’s and Alfred Russell Wallace’s ideas of natural selection with Mendelian genetics using the language of statistics. His other scientific contributions spanned the fields of physiology, biochemistry, and medical genetics – contributions that the evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith once said would “satisfy half a dozen ordinary mortals”.

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (1892-1964) is today best remembered as one of the founders of population genetics, which married Charles Darwin’s and Alfred Russell Wallace’s ideas of natural selection with Mendelian genetics using the language of statistics. His other scientific contributions spanned the fields of physiology, biochemistry, and medical genetics – contributions that the evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith once said would “satisfy half a dozen ordinary mortals”. IN LATE 2005

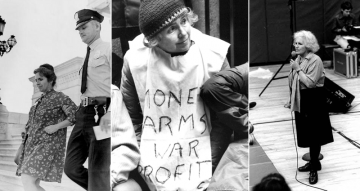

IN LATE 2005 Paley was an artist of the highest order, but she was also an activist, a pacifist, a mother, and a citizen. She saw her several callings as connected, and ideally as indistinct from each other, but when circumstance forced her to choose between protesting the war and making art, or standing up for free speech and making art, or building community and making art, she tended to back-burner the art-making. This may be one reason why her output was relatively slender and why it has been relatively undervalued. I don’t mean to suggest she’s neglected, exactly, only taken for granted at times. Well, whose mother hasn’t been?

Paley was an artist of the highest order, but she was also an activist, a pacifist, a mother, and a citizen. She saw her several callings as connected, and ideally as indistinct from each other, but when circumstance forced her to choose between protesting the war and making art, or standing up for free speech and making art, or building community and making art, she tended to back-burner the art-making. This may be one reason why her output was relatively slender and why it has been relatively undervalued. I don’t mean to suggest she’s neglected, exactly, only taken for granted at times. Well, whose mother hasn’t been?

If the book has a raison d’être beyond a mild anti-Brexit subtext, it is Barnes’s repeated plea not to patronise the past – to recognise trailblazers such as Pozzi without chiding his contemporaries for failing to be more like “us” (“We know more and better, don’t we?”). So even if the book hardly qualifies as a work of history, it still delivers a message that all historians should heed.

If the book has a raison d’être beyond a mild anti-Brexit subtext, it is Barnes’s repeated plea not to patronise the past – to recognise trailblazers such as Pozzi without chiding his contemporaries for failing to be more like “us” (“We know more and better, don’t we?”). So even if the book hardly qualifies as a work of history, it still delivers a message that all historians should heed. Commercial surrogacy, the practice of paying a woman to carry and birth a child whom she will not parent, is largely unregulated in America. It’s illegal, with rare exceptions, in three states: New York, Louisiana, and Michigan. But, most states have no surrogacy laws at all. Though the technology was invented in 1986, the concept still seems, for many, a bit sci-fi, and support for it does not follow obvious political fault lines. It is typically championed by the gay-rights community, who see it as the only reproductive technology that allows gay men to have biological children, and condemned by some feminists, who see it as yet another business that exploits the female body. In June, when the New York State Assembly considered a bill that would legalize paid surrogacy, Gloria Steinem vigorously opposed it. “Under this bill, women in economic need become commercialized vessels for rent, and the fetuses they carry become the property of others,” Steinem wrote in a statement.

Commercial surrogacy, the practice of paying a woman to carry and birth a child whom she will not parent, is largely unregulated in America. It’s illegal, with rare exceptions, in three states: New York, Louisiana, and Michigan. But, most states have no surrogacy laws at all. Though the technology was invented in 1986, the concept still seems, for many, a bit sci-fi, and support for it does not follow obvious political fault lines. It is typically championed by the gay-rights community, who see it as the only reproductive technology that allows gay men to have biological children, and condemned by some feminists, who see it as yet another business that exploits the female body. In June, when the New York State Assembly considered a bill that would legalize paid surrogacy, Gloria Steinem vigorously opposed it. “Under this bill, women in economic need become commercialized vessels for rent, and the fetuses they carry become the property of others,” Steinem wrote in a statement. Science seems under assault. Attacks come from many directions, ranging from the political realm to groups and individuals masquerading as scientific entities. There is even a real risk that scientific fact will eventually be reduced to just another opinion, even when those facts describe natural phenomena—the very purpose for which science was developed. Hastening this erosion are hyperbolic claims of “truth” that science is often perceived to make and that practicing researchers may themselves project, whether intentionally or not. I’m a researcher, and I get it. It seems difficult to explain the persistent success of scientific theories at describing nature, not to mention the constant march of technological advancement, without assigning at least some special epistemic status to those theories. I explore this challenge in my book,

Science seems under assault. Attacks come from many directions, ranging from the political realm to groups and individuals masquerading as scientific entities. There is even a real risk that scientific fact will eventually be reduced to just another opinion, even when those facts describe natural phenomena—the very purpose for which science was developed. Hastening this erosion are hyperbolic claims of “truth” that science is often perceived to make and that practicing researchers may themselves project, whether intentionally or not. I’m a researcher, and I get it. It seems difficult to explain the persistent success of scientific theories at describing nature, not to mention the constant march of technological advancement, without assigning at least some special epistemic status to those theories. I explore this challenge in my book,  I read with some interest Alex Byrne’s recent paper,

I read with some interest Alex Byrne’s recent paper,  It’s too easy to take laws of nature for granted. Sure, gravity is pulling us toward Earth today; but how do we know it won’t be pushing us away tomorrow? We extrapolate from past experience to future expectation, but what allows us to do that? “Humeans” (after David Hume, not a misspelling of “human”) think that what exists is just what actually happens in the universe, and the laws are simply convenient summaries of what happens. “Anti-Humeans” think that the laws have a reality of their own, bringing what happens next into existence. The debate has implications for the notion of possible worlds, and thus for counterfactuals and causation — would Y have happened if X hadn’t happened first? Ned Hall and I have a deep conversation that started out being about causation, but we quickly realized we had to get a bunch of interesting ideas on the table first. What we talk about helps clarify how we should think about our reality and others.

It’s too easy to take laws of nature for granted. Sure, gravity is pulling us toward Earth today; but how do we know it won’t be pushing us away tomorrow? We extrapolate from past experience to future expectation, but what allows us to do that? “Humeans” (after David Hume, not a misspelling of “human”) think that what exists is just what actually happens in the universe, and the laws are simply convenient summaries of what happens. “Anti-Humeans” think that the laws have a reality of their own, bringing what happens next into existence. The debate has implications for the notion of possible worlds, and thus for counterfactuals and causation — would Y have happened if X hadn’t happened first? Ned Hall and I have a deep conversation that started out being about causation, but we quickly realized we had to get a bunch of interesting ideas on the table first. What we talk about helps clarify how we should think about our reality and others. I have been triggered into writing this short essay by three events. One is reading Mukul Kesavan’s

I have been triggered into writing this short essay by three events. One is reading Mukul Kesavan’s