Joshua Rothman at The New Yorker:

Most science fiction takes place in a world in which “the future” has definitively arrived; the locomotive filmed by the Lumière brothers has finally burst through the screen. But in “Neuromancer” there was only a continuous arrival—an ongoing, alarming present. “Things aren’t different. Things are things,” an A.I. reports, after achieving a new level of consciousness. “You can’t let the little pricks generation-gap you,” one protagonist tells another, after an unnerving encounter with a teen-ager. In its uncertain sense of temporality—are we living in the future, or not?—“Neuromancer” was science fiction for the modern age. The novel’s influence has increased with time, establishing Gibson as an authority on the world to come.

Most science fiction takes place in a world in which “the future” has definitively arrived; the locomotive filmed by the Lumière brothers has finally burst through the screen. But in “Neuromancer” there was only a continuous arrival—an ongoing, alarming present. “Things aren’t different. Things are things,” an A.I. reports, after achieving a new level of consciousness. “You can’t let the little pricks generation-gap you,” one protagonist tells another, after an unnerving encounter with a teen-ager. In its uncertain sense of temporality—are we living in the future, or not?—“Neuromancer” was science fiction for the modern age. The novel’s influence has increased with time, establishing Gibson as an authority on the world to come.

The ten novels that Gibson has written since have slid steadily closer to the present. In the nineties, he wrote a trilogy set in the two-thousands. The novels he published in 2003, 2007, and 2010 were set in the year before their publication. (Only the inevitable delays of the publishing process prevented them from taking place in the years when they were written.) Many works of literary fiction claim to be set in the present day. In fact, they take place in the recent past, conjuring a world that feels real because it’s familiar, and therefore out of date. Gibson’s strategy of extreme presentness reflects his belief that the current moment is itself science-fictional. “The future is already here,” he has said. “It’s just not very evenly distributed.”

more here.

People engage in moral talk all the time. When they make moral claims in public, one common response is to dismiss them as virtue signallers. Twitter is full of these accusations: the actress Jameela Jamil is a ‘pathetic virtue-signalling twerp’, according to the journalist Piers Morgan; climate activists are virtue signallers, according to the conservative Manhattan Institute for Policy Research; vegetarianism is virtue signalling, according to the author Bjorn Lomborg (as these examples illustrate, the accusation seems more common from the Right than the Left). Accusing someone of virtue signalling is to accuse them of a kind of hypocrisy. The accused person claims to be deeply concerned about some moral issue but their main concern is – so the argument goes – with themselves. They’re not really concerned with changing minds, let alone with changing the world, but with displaying themselves in the best light possible. As the journalist James Bartholomew (who claimed in 2015 to have invented the phrase, but didn’t) puts it in The Spectator, virtue signalling is driven by ‘vanity and self-aggrandisement’, not concern with others.

People engage in moral talk all the time. When they make moral claims in public, one common response is to dismiss them as virtue signallers. Twitter is full of these accusations: the actress Jameela Jamil is a ‘pathetic virtue-signalling twerp’, according to the journalist Piers Morgan; climate activists are virtue signallers, according to the conservative Manhattan Institute for Policy Research; vegetarianism is virtue signalling, according to the author Bjorn Lomborg (as these examples illustrate, the accusation seems more common from the Right than the Left). Accusing someone of virtue signalling is to accuse them of a kind of hypocrisy. The accused person claims to be deeply concerned about some moral issue but their main concern is – so the argument goes – with themselves. They’re not really concerned with changing minds, let alone with changing the world, but with displaying themselves in the best light possible. As the journalist James Bartholomew (who claimed in 2015 to have invented the phrase, but didn’t) puts it in The Spectator, virtue signalling is driven by ‘vanity and self-aggrandisement’, not concern with others. When businessman Howard Bisla was tasked with saving a local shop from financial ruin, one of his first concerns was energy efficiency. In June 2018, he approached his local electricity provider in Sacramento, California, about upgrading the lights. The provider had another idea. It offered to install an experimental cooling system: panels that could stay colder than their surroundings, even under the blazing hot sun, without consuming energy. The aluminium-backed panels now sit on the shop’s roof, their mirrored surfaces coated with a thin cooling film and angled to the sky. They cool liquid in pipes underneath that run into the shop, and, together with new lights, have reduced electricity bills by around 15%. “Even on a hot day, they’re not hot,” Bisla says.

When businessman Howard Bisla was tasked with saving a local shop from financial ruin, one of his first concerns was energy efficiency. In June 2018, he approached his local electricity provider in Sacramento, California, about upgrading the lights. The provider had another idea. It offered to install an experimental cooling system: panels that could stay colder than their surroundings, even under the blazing hot sun, without consuming energy. The aluminium-backed panels now sit on the shop’s roof, their mirrored surfaces coated with a thin cooling film and angled to the sky. They cool liquid in pipes underneath that run into the shop, and, together with new lights, have reduced electricity bills by around 15%. “Even on a hot day, they’re not hot,” Bisla says. ‘A poem is not a lecture; a story is not an argument. The way poems and stories work on our minds is not by logic, but by their capacity to enchant, to excite, to move, to inspire.’ So writes Philip Pullman in his

‘A poem is not a lecture; a story is not an argument. The way poems and stories work on our minds is not by logic, but by their capacity to enchant, to excite, to move, to inspire.’ So writes Philip Pullman in his  I am not altogether incurious, but one entity about which I have over the years felt little curiosity is my own body. Until recently, I could not have told you the function of my, or anyone else’s, pancreas, spleen, or gallbladder. I’d just as soon not have known that I have kidneys, and was less than certain of their exact whereabouts, apart from knowing that they reside somewhere in the region of my lower back. As for my entrails, the yards of intestines winding through my body, the less I knew about them the better, though I have always liked the sound of the word “duodenum.” About the cells and chromosomes, the hormones and microbes crawling and swimming about in my body, let us not speak.

I am not altogether incurious, but one entity about which I have over the years felt little curiosity is my own body. Until recently, I could not have told you the function of my, or anyone else’s, pancreas, spleen, or gallbladder. I’d just as soon not have known that I have kidneys, and was less than certain of their exact whereabouts, apart from knowing that they reside somewhere in the region of my lower back. As for my entrails, the yards of intestines winding through my body, the less I knew about them the better, though I have always liked the sound of the word “duodenum.” About the cells and chromosomes, the hormones and microbes crawling and swimming about in my body, let us not speak. The last time I saw Sonny Mehta was October 2018. I was pregnant with my second child and was in New York for a short trip. Come and get me for a drink, he said. And so I went to the Knopf offices on Broadway to pick him up.

The last time I saw Sonny Mehta was October 2018. I was pregnant with my second child and was in New York for a short trip. Come and get me for a drink, he said. And so I went to the Knopf offices on Broadway to pick him up. Knees in Asia are the most likely to have a fabella, and knees in Africa are the least. The humerus can be used to determine the sex of a Thai skeleton. A French courtship researcher retracted his paper titled “High Heels Increase Women’s Attractiveness,” and female Instagram influencers were found to face criticism for seeming both too real and too fake. Male green-veined white butterflies use volatile flower compounds to create the anti-aphrodisiac pheromone they transfer to females during mating to make them unattractive to other males. The loudest known avian vocalization was observed among male white bellbirds of the northern Amazon, who scream their crescendo directly at females perched next to them; the study’s authors expressed uncertainty as to why the females put up with the risk of hearing damage. Researchers denominated three essential categories of arrogance and found that narcissists are less prone to depression. Escapism predicts problematic online gaming. Scientists offered a path to freedom for an all-male colony of wood ants who were trapped for years in an abandoned Polish nuclear bunker but had continued to thrive because of cannibalism. Doctors expressed concern that men might unnecessarily second-guess medical advice by soliciting opinions from Reddit users about photos of their diseased penises. Itchiness makes Europeans about twice as likely to contemplate suicide.

Knees in Asia are the most likely to have a fabella, and knees in Africa are the least. The humerus can be used to determine the sex of a Thai skeleton. A French courtship researcher retracted his paper titled “High Heels Increase Women’s Attractiveness,” and female Instagram influencers were found to face criticism for seeming both too real and too fake. Male green-veined white butterflies use volatile flower compounds to create the anti-aphrodisiac pheromone they transfer to females during mating to make them unattractive to other males. The loudest known avian vocalization was observed among male white bellbirds of the northern Amazon, who scream their crescendo directly at females perched next to them; the study’s authors expressed uncertainty as to why the females put up with the risk of hearing damage. Researchers denominated three essential categories of arrogance and found that narcissists are less prone to depression. Escapism predicts problematic online gaming. Scientists offered a path to freedom for an all-male colony of wood ants who were trapped for years in an abandoned Polish nuclear bunker but had continued to thrive because of cannibalism. Doctors expressed concern that men might unnecessarily second-guess medical advice by soliciting opinions from Reddit users about photos of their diseased penises. Itchiness makes Europeans about twice as likely to contemplate suicide.

The approach of a decade’s end draws the mind to those sorts of considerations, the way in which the arbitrary conclusion of a certain segment of calendrical time imposes order onto the disorder of human events. Our approaching decade’s conclusion is the rare variety of prediction that necessarily and by definition shall absolutely come to pass (even if all the missiles should go off before the Times Square ball drops).

The approach of a decade’s end draws the mind to those sorts of considerations, the way in which the arbitrary conclusion of a certain segment of calendrical time imposes order onto the disorder of human events. Our approaching decade’s conclusion is the rare variety of prediction that necessarily and by definition shall absolutely come to pass (even if all the missiles should go off before the Times Square ball drops). Written in 1947, Klein’s Monotone-Silence Symphony has been performed in Paris, New York City, and most recently, at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., for a total of some ten performances—occurrences more rare than a solar eclipse. Now at a cathedral near me. A few years ago, wanting to branch out from the Baroque, Classical and Romantic repertoire that I had been singing, I joined an a cappella chamber chorus that performs only new music, nothing written before 1980. I love dissonance, crunches, uncommon intervals, uncommon and shifting meters, cascading tritones, so when an email came from a music blogger not to attend the Klein but to sing in it—I jumped.

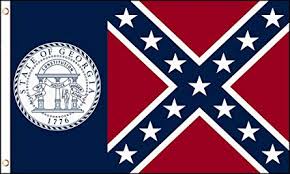

Written in 1947, Klein’s Monotone-Silence Symphony has been performed in Paris, New York City, and most recently, at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., for a total of some ten performances—occurrences more rare than a solar eclipse. Now at a cathedral near me. A few years ago, wanting to branch out from the Baroque, Classical and Romantic repertoire that I had been singing, I joined an a cappella chamber chorus that performs only new music, nothing written before 1980. I love dissonance, crunches, uncommon intervals, uncommon and shifting meters, cascading tritones, so when an email came from a music blogger not to attend the Klein but to sing in it—I jumped. And flags change or, rather, are subject to change. As I mentioned before, the Georgia state flag I grew up with featured the Confederate battle flag. We learned the stories behind the Betsy Ross flag with its thirteen stars and the current United States flag and its fifty stars, but how we came to have the state flag I grew up with wasn’t taught in school. Turns out Georgia didn’t have an official flag until 1879. Before that, it had a state seal, which was adopted in 1799, and local militias had to incorporate the coat of arms from the state seal into their hand-sewn banners. That 1879 flag, Georgia’s first official state flag, was modeled on the Stars and Bars, the first national flag of the Confederacy. The Confederacy itself changed its flag several times during the war, and the flag of Robert E. Lee’s army, the Confederate battle flag, was incorporated into subsequent iterations. In 1956 the Georgia General Assembly changed the state flag, replacing the bars on the field with the Confederate battle flag itself. Some lawmakers claimed they wanted to honor Confederate soldiers for the then upcoming centennial of the Civil War. But given that the legislation to change the flag came on the heels of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, placing the Confederate battle flag on the state flag seems to make a pretty clear statement of how those lawmakers and many of their constituency felt about integration. It was an expression of their support of the Confederacy’s white supremacist cause, then in the form of Jim Crow segregation.

And flags change or, rather, are subject to change. As I mentioned before, the Georgia state flag I grew up with featured the Confederate battle flag. We learned the stories behind the Betsy Ross flag with its thirteen stars and the current United States flag and its fifty stars, but how we came to have the state flag I grew up with wasn’t taught in school. Turns out Georgia didn’t have an official flag until 1879. Before that, it had a state seal, which was adopted in 1799, and local militias had to incorporate the coat of arms from the state seal into their hand-sewn banners. That 1879 flag, Georgia’s first official state flag, was modeled on the Stars and Bars, the first national flag of the Confederacy. The Confederacy itself changed its flag several times during the war, and the flag of Robert E. Lee’s army, the Confederate battle flag, was incorporated into subsequent iterations. In 1956 the Georgia General Assembly changed the state flag, replacing the bars on the field with the Confederate battle flag itself. Some lawmakers claimed they wanted to honor Confederate soldiers for the then upcoming centennial of the Civil War. But given that the legislation to change the flag came on the heels of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, placing the Confederate battle flag on the state flag seems to make a pretty clear statement of how those lawmakers and many of their constituency felt about integration. It was an expression of their support of the Confederacy’s white supremacist cause, then in the form of Jim Crow segregation. Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl tells a series of stories that we already know, but it achieves its familiar ends through decidedly unfamiliar means. Andrea Lawlor’s first novel presents us with the queer young adulthood of Paul, who possesses a seemingly magical skill: the ability to change form, to will his body into whatever shape he would like it to take.

Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl tells a series of stories that we already know, but it achieves its familiar ends through decidedly unfamiliar means. Andrea Lawlor’s first novel presents us with the queer young adulthood of Paul, who possesses a seemingly magical skill: the ability to change form, to will his body into whatever shape he would like it to take. The answer is that the last century of science has partially recapitulated Aristotle’s teachings on nature, for the most part unwittingly. Since roughly the turn of the twentieth century, the scientific enterprise has focused not only on the elemental, but increasingly also on large-scale phenomena: solids, fluids, organisms, ecosystems, human behavior, and computing machines. Scientists have often maintained that these systems cannot be understood solely in terms of action at the lowest levels of organization. Thus one hears of “systems theory” or “the theory of complex systems,” of “holism,” “irreducibility,” “downward causation,” “information theory,” and other musings from scientists that assert, to quote the physicist Philip Anderson, that “

The answer is that the last century of science has partially recapitulated Aristotle’s teachings on nature, for the most part unwittingly. Since roughly the turn of the twentieth century, the scientific enterprise has focused not only on the elemental, but increasingly also on large-scale phenomena: solids, fluids, organisms, ecosystems, human behavior, and computing machines. Scientists have often maintained that these systems cannot be understood solely in terms of action at the lowest levels of organization. Thus one hears of “systems theory” or “the theory of complex systems,” of “holism,” “irreducibility,” “downward causation,” “information theory,” and other musings from scientists that assert, to quote the physicist Philip Anderson, that “ The art of Bill Traylor comes to us with the ghosts of slave ships, lynchings, chain gangs, Jim Crow, justice denied — an American night-story without end. Born in Alabama in 1853, Traylor was 9 years old when Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and 12 when slavery was abolished with the 13th Amendment. He bore his owner’s name for life and resided for 55 years near the plantation where he was born; then he moved to nearby Montgomery County, where he remained until his death in 1949. In 1927 or 1928, he moved alone to the city of Montgomery, and in 1929, his son was killed by police. Ten years later, when Traylor was 85 and essentially homeless, he began to draw and paint on the streets of Montgomery, and a massive arc of art as powerful and profound as any in the 20th century shot out of him. His drawings and paintings in ink, pencil, and gouache were made on found cardboard, candy-box tops, and other odds and ends. Today, only four years of his output remain, yet we have about 1,200 works.

The art of Bill Traylor comes to us with the ghosts of slave ships, lynchings, chain gangs, Jim Crow, justice denied — an American night-story without end. Born in Alabama in 1853, Traylor was 9 years old when Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and 12 when slavery was abolished with the 13th Amendment. He bore his owner’s name for life and resided for 55 years near the plantation where he was born; then he moved to nearby Montgomery County, where he remained until his death in 1949. In 1927 or 1928, he moved alone to the city of Montgomery, and in 1929, his son was killed by police. Ten years later, when Traylor was 85 and essentially homeless, he began to draw and paint on the streets of Montgomery, and a massive arc of art as powerful and profound as any in the 20th century shot out of him. His drawings and paintings in ink, pencil, and gouache were made on found cardboard, candy-box tops, and other odds and ends. Today, only four years of his output remain, yet we have about 1,200 works. In the early 20

In the early 20 Emily Dickinson’s poems are obsessed with youthful themes: fame, popularity, intense bouts of emotion and, of course, a fetishization of death. Her work isn’t changed in Dickinson. The stanzas are true to the source material. Modernizing the way characters speak to each other, but keeping the poems consistent, allows Dickinson’s words to feel more approachable for an audience that came into their own by way of Lil Peep Instagram live-streams and SoundCloud emo rap. Most brilliantly, Dickinson isn’t trying to be a teen show. That’s precisely why it works as one. It kind of stumbles into itself, finding its footing along the way. There isn’t any clear direction or structure to help it stay on the same path. Dickinson doesn’t shy away from ludicrousness, but leans into it unabashedly. It’s an “unapologetic, crying on the floor at two in the morning, flirting with the fetishization of death even when floating on the undeniable highness of life” type of disaster.

Emily Dickinson’s poems are obsessed with youthful themes: fame, popularity, intense bouts of emotion and, of course, a fetishization of death. Her work isn’t changed in Dickinson. The stanzas are true to the source material. Modernizing the way characters speak to each other, but keeping the poems consistent, allows Dickinson’s words to feel more approachable for an audience that came into their own by way of Lil Peep Instagram live-streams and SoundCloud emo rap. Most brilliantly, Dickinson isn’t trying to be a teen show. That’s precisely why it works as one. It kind of stumbles into itself, finding its footing along the way. There isn’t any clear direction or structure to help it stay on the same path. Dickinson doesn’t shy away from ludicrousness, but leans into it unabashedly. It’s an “unapologetic, crying on the floor at two in the morning, flirting with the fetishization of death even when floating on the undeniable highness of life” type of disaster.