Peter Wehner in The Atlantic:

The president’s misinformation and mendacity about the coronavirus are head-snapping. He claimed that it was contained in America when it was actually spreading. He claimed that we had “shut it down” when we had not. He claimed that testing was available when it wasn’t. He claimed that the coronavirus will one day disappear “like a miracle”; it won’t. He claimed that a vaccine would be available in months; Fauci says it will not be available for a year or more. Trump falsely blamed the Obama administration for impeding coronavirus testing. He stated that the coronavirus first hit the United States later than it actually did. (He said that it was three weeks prior to the point at which he spoke; the actual figure was twice that.) The president claimed that the number of cases in Italy was getting “much better” when it was getting much worse. And in one of the more stunning statements an American president has ever made, Trump admitted that his preference was to keep a cruise ship off the California coast rather than allowing it to dock, because he wanted to keep the number of reported cases of the coronavirus artificially low. “I like the numbers,” Trump said. “I would rather have the numbers stay where they are. But if they want to take them off, they’ll take them off. But if that happens, all of a sudden your 240 [cases] is obviously going to be a much higher number, and probably the 11 [deaths] will be a higher number too.” (Cooler heads prevailed, and over the president’s objections, the Grand Princess was allowed to dock at the Port of Oakland.)

On and on it goes.

To make matters worse, the president delivered an Oval Office address that was meant to reassure the nation and the markets but instead shook both. The president’s delivery was awkward and stilted; worse, at several points, the president, who decided to ad-lib the teleprompter speech, misstated his administration’s own policies, which the administration had to correct. Stock futures plunged even as the president was still delivering his speech. In his address, the president called for Americans to “unify together as one nation and one family,” despite having referred to Washington Governor Jay Inslee as a “snake” days before the speech and attacking Democrats the morning after it. As The Washington Post’s Dan Balz put it, “Almost everything that could have gone wrong with the speech did go wrong.”

More here.

Fifty years ago, the screenwriter Robert Towne said to his girlfriend, “I want to write a movie for Jack.” He meant Nicholson — in those days, and possibly even now, there is only one Jack — who had just had his breakout role in “Easy Rider.” “A detective movie,” Towne explained. “Maybe Jane Fonda for the blonde.” He knew he wanted to set it in Los Angeles before the war, like a Raymond Chandler novel. But that was about the extent of it. When he told Nicholson, the actor naturally asked, “What’s it about?”

Fifty years ago, the screenwriter Robert Towne said to his girlfriend, “I want to write a movie for Jack.” He meant Nicholson — in those days, and possibly even now, there is only one Jack — who had just had his breakout role in “Easy Rider.” “A detective movie,” Towne explained. “Maybe Jane Fonda for the blonde.” He knew he wanted to set it in Los Angeles before the war, like a Raymond Chandler novel. But that was about the extent of it. When he told Nicholson, the actor naturally asked, “What’s it about?” What we are seeing right now is the collapse of civic authority and public trust at what is only the beginning of a protracted crisis. In the face of an onrushing pandemic, the United States has exhibited a near-total evacuation of responsibility and political leadership — a sociopathic disinterest in performing the basic function of government, which is to protect its citizens.

What we are seeing right now is the collapse of civic authority and public trust at what is only the beginning of a protracted crisis. In the face of an onrushing pandemic, the United States has exhibited a near-total evacuation of responsibility and political leadership — a sociopathic disinterest in performing the basic function of government, which is to protect its citizens. The Memory Eaters is told in the context of 1970s and 1980s New York City. The memoir moves from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post- traumatic stress disorder. The Memory Eaters is about consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia. More can be found at

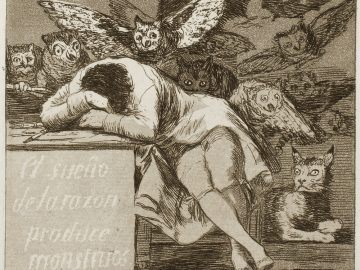

The Memory Eaters is told in the context of 1970s and 1980s New York City. The memoir moves from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post- traumatic stress disorder. The Memory Eaters is about consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia. More can be found at  Elizabeth Kadetsky: Coming of age in the 1970s, I was exposed, through my mother, to a lot of what you might call groovy spirituality that enshrined this idea that you would find truth if you just relaxed your brain enough to let it come to you. This was the thinking behind the versions of so many of the trendy ideologies that we adopted: I Ching, astrology, Ouija Board, palm reading. I don’t think that we believed in the magic of any of these systems in the least. The idea was that these were all tools that helped you get more in tune with your subconscious. So, my mother’s ideas about “watching” definitely came out of that, that there was a sort of divine intelligence that you could tap into through paying close attention in both dream and waking life. It’s funny because when I think about it now I see the pitfalls of this mindset, especially for the writer.

Elizabeth Kadetsky: Coming of age in the 1970s, I was exposed, through my mother, to a lot of what you might call groovy spirituality that enshrined this idea that you would find truth if you just relaxed your brain enough to let it come to you. This was the thinking behind the versions of so many of the trendy ideologies that we adopted: I Ching, astrology, Ouija Board, palm reading. I don’t think that we believed in the magic of any of these systems in the least. The idea was that these were all tools that helped you get more in tune with your subconscious. So, my mother’s ideas about “watching” definitely came out of that, that there was a sort of divine intelligence that you could tap into through paying close attention in both dream and waking life. It’s funny because when I think about it now I see the pitfalls of this mindset, especially for the writer. Japan is reporting its first case of a person becoming reinfected with the coronavirus after showing signs they had fully recovered,

Japan is reporting its first case of a person becoming reinfected with the coronavirus after showing signs they had fully recovered,  Across the globe, a

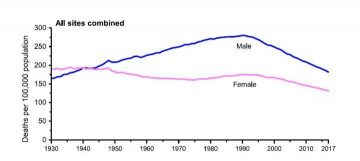

Across the globe, a  This year’s report showed that

This year’s report showed that  Probably this is not the end of the world. But a plague is creeping around the globe at a seemingly exponential rate, killing some of us and affecting all of us. And this pandemic is only the most recent and most sudden of a series of afflictions facing humanity. We are rapidly replacing our natural habitat with one that is, on the one hand, made by human beings, and, on the other, proving difficult for us to manage—a situation we euphemistically refer to as “climate change.” On the political front, the past decade has seen a rise in civil unrest worldwide, and the leaders of a number of countries have given us reason to be less optimistic than we used to be about the prospects for global democracy. Given the ever-cheapening technology, weapons—including those of mass destruction—must be proliferating unnoticed. And all of the above is happening against a backdrop of low economic growth and stagnant wages, at least for most of the world’s wealthiest countries.

Probably this is not the end of the world. But a plague is creeping around the globe at a seemingly exponential rate, killing some of us and affecting all of us. And this pandemic is only the most recent and most sudden of a series of afflictions facing humanity. We are rapidly replacing our natural habitat with one that is, on the one hand, made by human beings, and, on the other, proving difficult for us to manage—a situation we euphemistically refer to as “climate change.” On the political front, the past decade has seen a rise in civil unrest worldwide, and the leaders of a number of countries have given us reason to be less optimistic than we used to be about the prospects for global democracy. Given the ever-cheapening technology, weapons—including those of mass destruction—must be proliferating unnoticed. And all of the above is happening against a backdrop of low economic growth and stagnant wages, at least for most of the world’s wealthiest countries.

György Konrád passed away after prolonged illness on September 13, 2019, at the age of 86, two days after the architect László Rajk Jr. (who had just turned 70) and less than two months after the philosopher Ágnes Heller at the age of 90. The departure of three prominent Hungarian public intellectuals admired in Hungary and the world over has led commentators — perhaps especially since these deaths came so soon after those of Imre Kertész and Péter Esterházy — to mark “the passing of a key intellectual generation” and even “the end of an era.”

György Konrád passed away after prolonged illness on September 13, 2019, at the age of 86, two days after the architect László Rajk Jr. (who had just turned 70) and less than two months after the philosopher Ágnes Heller at the age of 90. The departure of three prominent Hungarian public intellectuals admired in Hungary and the world over has led commentators — perhaps especially since these deaths came so soon after those of Imre Kertész and Péter Esterházy — to mark “the passing of a key intellectual generation” and even “the end of an era.” How to Keep Your House from Becoming a Disaster Area

How to Keep Your House from Becoming a Disaster Area Think of Bloomsbury and what might spring to mind is its “orderly profligacy and passionate coldness”. (The phrase is Elizabeth Hardwick’s, in one of her early essay/reviews for The New York Review of Books.) But there was always more to Bloomsbury than this suggests. First came the actual geographical locality – the streets and squares and architecture of a part of central London – and then the associations imposed on top of it: literary, scholarly, urbane or bohemian. Bloomsbury as an idea continues to reverberate, in ways both gossipy and profound. Bedazzling sexual intrigues and a spot of intellectual hauteur are only a part of it. And however many words have been expended on Bloomsbury (and there have been a lot), there is always more to be said. Francesca Wade’s superbly engaging Square Haunting takes up the theme, but at the same time narrows and intensifies its focus. Wade homes in on a single square, Mecklenburgh Square, which is not at the heart of the potent locality but rather on its periphery.

Think of Bloomsbury and what might spring to mind is its “orderly profligacy and passionate coldness”. (The phrase is Elizabeth Hardwick’s, in one of her early essay/reviews for The New York Review of Books.) But there was always more to Bloomsbury than this suggests. First came the actual geographical locality – the streets and squares and architecture of a part of central London – and then the associations imposed on top of it: literary, scholarly, urbane or bohemian. Bloomsbury as an idea continues to reverberate, in ways both gossipy and profound. Bedazzling sexual intrigues and a spot of intellectual hauteur are only a part of it. And however many words have been expended on Bloomsbury (and there have been a lot), there is always more to be said. Francesca Wade’s superbly engaging Square Haunting takes up the theme, but at the same time narrows and intensifies its focus. Wade homes in on a single square, Mecklenburgh Square, which is not at the heart of the potent locality but rather on its periphery. As I fall asleep, I leave my body and my soul behind, all the while palpably returning back to my body and my soul. But what is actually going on here? It is not my body that has changed, or my soul, but rather my relation to both. By day, when I’m awake, I usually observe my body from without, and although I am only capable of imagining myself as a physical body, I don’t identify myself with it. In a similar way, I don’t fully identify with my soul either. If I’m awake, for the most part I think of it, as it were, as someone (or something), which cannot exist without me, and yet is not completely identical to me. I would almost speak of it in the third-person singular. This is Descartes’s final inheritance; not even I can avoid his influence. In the moment when I began to speak about the body or about the soul, I unwittingly behave as if it were possible to distinguish between them. And in doing so I imperceptibly differentiate myself from them. I create a differentiation between the soul and the body.

As I fall asleep, I leave my body and my soul behind, all the while palpably returning back to my body and my soul. But what is actually going on here? It is not my body that has changed, or my soul, but rather my relation to both. By day, when I’m awake, I usually observe my body from without, and although I am only capable of imagining myself as a physical body, I don’t identify myself with it. In a similar way, I don’t fully identify with my soul either. If I’m awake, for the most part I think of it, as it were, as someone (or something), which cannot exist without me, and yet is not completely identical to me. I would almost speak of it in the third-person singular. This is Descartes’s final inheritance; not even I can avoid his influence. In the moment when I began to speak about the body or about the soul, I unwittingly behave as if it were possible to distinguish between them. And in doing so I imperceptibly differentiate myself from them. I create a differentiation between the soul and the body. Rape, writes Christina Lamb at the start of this deeply traumatic and important book, is “the cheapest weapon known to man”. It is also one of the oldest, with the Book of Deuteronomy giving its blessing to soldiers who find “a beautiful woman” among the captives taken in battle. If “you desire to take her”, it says, “you may”. As the American writer

Rape, writes Christina Lamb at the start of this deeply traumatic and important book, is “the cheapest weapon known to man”. It is also one of the oldest, with the Book of Deuteronomy giving its blessing to soldiers who find “a beautiful woman” among the captives taken in battle. If “you desire to take her”, it says, “you may”. As the American writer