Anita Ho in Aeon:

‘I wouldn’t show them the note,’ a retired nurse, told my mother. It was a request to meet with my father’s physicians. He had undergone a cardiac surgery, and soon after became lethargic and difficult to rouse. The nurses thought he was simply fatigued from his procedure, and my mother didn’t want to question their professional judgment. Two days later, my father suffered an acute respiratory failure and was rushed to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was intubated and remained dependent on a respirator for days. The nurses told my mother that the doctors were considering a tracheostomy, but up to that point no ICU physician (called an ‘intensivist’) had so much as talked to my family.

‘I wouldn’t show them the note,’ a retired nurse, told my mother. It was a request to meet with my father’s physicians. He had undergone a cardiac surgery, and soon after became lethargic and difficult to rouse. The nurses thought he was simply fatigued from his procedure, and my mother didn’t want to question their professional judgment. Two days later, my father suffered an acute respiratory failure and was rushed to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was intubated and remained dependent on a respirator for days. The nurses told my mother that the doctors were considering a tracheostomy, but up to that point no ICU physician (called an ‘intensivist’) had so much as talked to my family.

Intensivists were not at the bedside during the limited visiting hours and, as they rotated, a series of different intensivists attended to my father. So my mother was left to wait outside the ICU in the remote chance that she would run into my father’s doctor, but nobody told her the name of the attending physician du jour, and the doctors’ faces were often hidden behind surgical masks as they walked the halls. So, with my help, she had drawn up the note, requesting a meeting. But it was to no avail. ‘The doctors might think your family is difficult,’ the nurse said.

I wondered why the doctors didn’t hold a family meeting to discuss my father’s prognosis and clinical options. While my mother wanted to speak to at least one of the intensivists, attempts to make appointments were met with reluctance. The nurses said the doctors were busy, that they had to uphold patient privacy and confidentiality. My mother started to blame herself for not insisting on further investigation regarding my father’s lethargy, and she was anxious about the lack of information. Worse, the insinuation that she would be bothering the busy clinicians for wanting a meeting with them intimidated her. She was sternly warned by a nurse not to overstay the visiting hours. I am a bioethicist who has worked alongside clinicians in supporting patients and families making complex and rending care decisions. I have seen how physicians are bombarded with demands. Meeting with families requires not only coordination but energy: it is emotionally draining for clinicians to share grim prognoses with patients and families.

More here.

Why is consciousness so perplexing to so many? Perhaps, owing to our being conscious, we regard ourselves as experts on the matter, and it seems to us blindingly obvious that consciousness could not possibly be a brain state or process. We have a front-row seat, an unmediated first-hand awareness of what conscious experiences are like, and we know well-enough what brain processes are like. The two could not be more different. In the hands of philosophers, this sentiment is transmuted into the doctrine that consciousness cannot be identified with, or ‘reduced to’, anything physical. The reduction in question must be a relation among explanations, or predicates, not as it is sometimes cast, a relation among properties. What would it be to reduce something to something else? If the As are not reducible to the Bs, explanations of the As could not be derived from explanations of the Bs, nor could A-terms be analysed or paraphrased in a B-vocabulary.

Why is consciousness so perplexing to so many? Perhaps, owing to our being conscious, we regard ourselves as experts on the matter, and it seems to us blindingly obvious that consciousness could not possibly be a brain state or process. We have a front-row seat, an unmediated first-hand awareness of what conscious experiences are like, and we know well-enough what brain processes are like. The two could not be more different. In the hands of philosophers, this sentiment is transmuted into the doctrine that consciousness cannot be identified with, or ‘reduced to’, anything physical. The reduction in question must be a relation among explanations, or predicates, not as it is sometimes cast, a relation among properties. What would it be to reduce something to something else? If the As are not reducible to the Bs, explanations of the As could not be derived from explanations of the Bs, nor could A-terms be analysed or paraphrased in a B-vocabulary. This is a special episode of Mindscape, thrown together quickly. Many thanks to Tara Smith for joining me on short notice. Tara is an epidemiologist, and a great person to talk to about the novel coronavirus (and its associated disease, COVID-19) pandemic currently threatening the world. We talk about what viruses are, how they spread, and a lot of the science behind virology and pandemics. We also take a practical turn, talking about what measures (washing hands, social distancing, self-isolation) are useful at combating the spread of the virus, and which (wearing masks) are probably not. Then we look to the future, to ask what the endgame here is; Tara suggests that the kind of drastic measure we are currently putting up with might last a long time indeed.

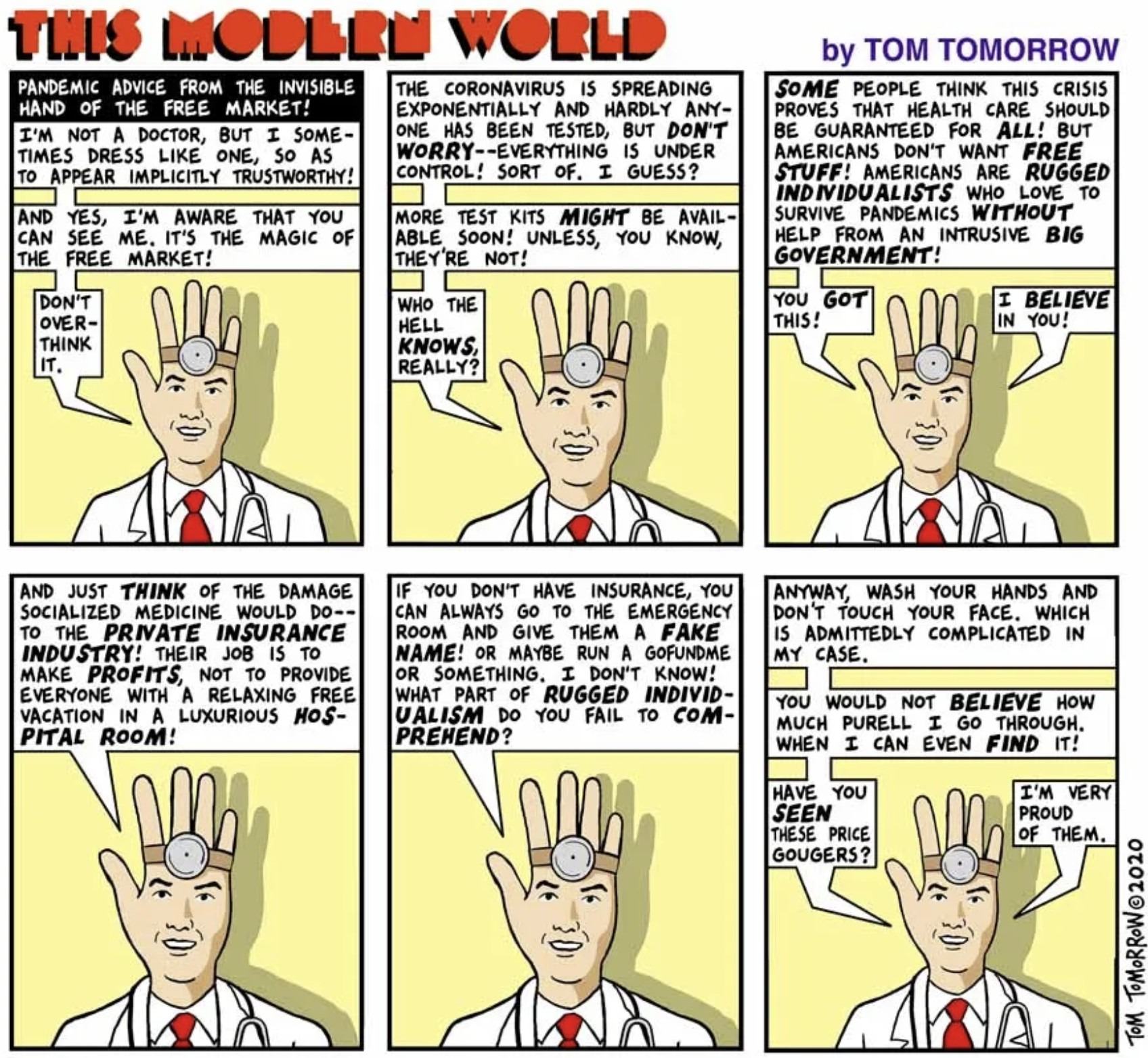

This is a special episode of Mindscape, thrown together quickly. Many thanks to Tara Smith for joining me on short notice. Tara is an epidemiologist, and a great person to talk to about the novel coronavirus (and its associated disease, COVID-19) pandemic currently threatening the world. We talk about what viruses are, how they spread, and a lot of the science behind virology and pandemics. We also take a practical turn, talking about what measures (washing hands, social distancing, self-isolation) are useful at combating the spread of the virus, and which (wearing masks) are probably not. Then we look to the future, to ask what the endgame here is; Tara suggests that the kind of drastic measure we are currently putting up with might last a long time indeed.

To stop coronavirus we will need to radically change almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health, educate our kids, take care of family members.

To stop coronavirus we will need to radically change almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health, educate our kids, take care of family members.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared COVID-19—the acute respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus—a

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared COVID-19—the acute respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus—a  One of the best-known sketches from Monty Python’s Flying Circus features John Cleese as a bowler-hatted bureaucrat with the fictional

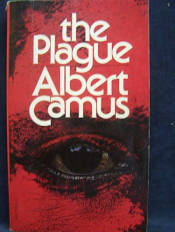

One of the best-known sketches from Monty Python’s Flying Circus features John Cleese as a bowler-hatted bureaucrat with the fictional  Usually a question like this is theoretical: What would it be like to find your town, your state, your country, shut off from the rest of the world, its citizens confined to their homes, as a contagion spreads, infecting thousands, and subjecting thousands more to quarantine? How would you cope if an epidemic disrupted daily life, closing schools, packing hospitals, and putting social gatherings, sporting events and concerts, conferences, festivals and travel plans on indefinite hold?

Usually a question like this is theoretical: What would it be like to find your town, your state, your country, shut off from the rest of the world, its citizens confined to their homes, as a contagion spreads, infecting thousands, and subjecting thousands more to quarantine? How would you cope if an epidemic disrupted daily life, closing schools, packing hospitals, and putting social gatherings, sporting events and concerts, conferences, festivals and travel plans on indefinite hold? The words social distancing have already defined 2020, and everyone is already tired of them (and

The words social distancing have already defined 2020, and everyone is already tired of them (and  O

O As the new coronavirus marches around the globe, countries with escalating outbreaks are eager to learn whether China’s extreme lockdowns were responsible for bringing the crisis there under control. Other nations are now following China’s lead and limiting movement within their borders, while dozens of countries have restricted international visitors. In mid-January, Chinese authorities introduced unprecedented measures to contain the virus, stopping movement in and out of Wuhan, the centre of the epidemic, and 15 other cities in Hubei province — home to more than 60 million people. Flights and trains were suspended, and roads were blocked. Soon after, people in many Chinese cities were told to stay home and venture out only to get food or medical help. Some 760 million people, roughly half the country’s population, were confined to their homes, according to the

As the new coronavirus marches around the globe, countries with escalating outbreaks are eager to learn whether China’s extreme lockdowns were responsible for bringing the crisis there under control. Other nations are now following China’s lead and limiting movement within their borders, while dozens of countries have restricted international visitors. In mid-January, Chinese authorities introduced unprecedented measures to contain the virus, stopping movement in and out of Wuhan, the centre of the epidemic, and 15 other cities in Hubei province — home to more than 60 million people. Flights and trains were suspended, and roads were blocked. Soon after, people in many Chinese cities were told to stay home and venture out only to get food or medical help. Some 760 million people, roughly half the country’s population, were confined to their homes, according to the  To understand why the world economy is in grave peril because of the spread of coronavirus, it helps to grasp one idea that is at once blindingly obvious and sneakily profound.

To understand why the world economy is in grave peril because of the spread of coronavirus, it helps to grasp one idea that is at once blindingly obvious and sneakily profound. “What good is half a wing?” That’s the rhetorical question often asked by people who have trouble accepting Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Of course it’s a very answerable question, but figuring out what exactly the answer is leads us to some fascinating biology. Neil Shubin should know: he is the co-discoverer of

“What good is half a wing?” That’s the rhetorical question often asked by people who have trouble accepting Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Of course it’s a very answerable question, but figuring out what exactly the answer is leads us to some fascinating biology. Neil Shubin should know: he is the co-discoverer of  I have never been much of a runner, but on Saturday I find myself suiting up for exercise and meeting a friend for a run. It has been a week since the Italian prime minister

I have never been much of a runner, but on Saturday I find myself suiting up for exercise and meeting a friend for a run. It has been a week since the Italian prime minister  The Belgrade installation of Sound Corridor missed an opportunity to connect Abramović’s work to that of her contemporaries. But it was nevertheless a startling introduction to an exhibition with a haunting soundscape, evocative of melancholy, death, and nostalgic enchantment. Moving from the corridor of recorded gunfire into the lobby, one could hear Abramović’s screams from the video Freeing the Voice (1975) on the second floor. For that performance at the SKC, the artist lay on her back screaming for three hours, until she lost her voice. On the first floor, a large but quiet black-box installation featured video footage from The Artist Is Present (2010), the performance staged during her retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Opposite this installation stood Private Archaeology (1997–2015), a set of wooden cabinets holding a collection of sketches, collages, artifacts, and ephemera from Abramović’s archive, a deeply self-mythologizing installation that surprisingly did not include any reference to her SKC involvement. At the top of the stairs, large projections showed black-and-white footage of some of Abramović’s best-known works: Freeing the Voice, mentioned above; Freeing the Body (1976), in which she wrapped her head in a black scarf and danced for eight hours, until she collapsed; and several of her performances made in collaboration with German artist Ulay, including one where they slam their bodies together, and another where they sit opposite each other and scream.

The Belgrade installation of Sound Corridor missed an opportunity to connect Abramović’s work to that of her contemporaries. But it was nevertheless a startling introduction to an exhibition with a haunting soundscape, evocative of melancholy, death, and nostalgic enchantment. Moving from the corridor of recorded gunfire into the lobby, one could hear Abramović’s screams from the video Freeing the Voice (1975) on the second floor. For that performance at the SKC, the artist lay on her back screaming for three hours, until she lost her voice. On the first floor, a large but quiet black-box installation featured video footage from The Artist Is Present (2010), the performance staged during her retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Opposite this installation stood Private Archaeology (1997–2015), a set of wooden cabinets holding a collection of sketches, collages, artifacts, and ephemera from Abramović’s archive, a deeply self-mythologizing installation that surprisingly did not include any reference to her SKC involvement. At the top of the stairs, large projections showed black-and-white footage of some of Abramović’s best-known works: Freeing the Voice, mentioned above; Freeing the Body (1976), in which she wrapped her head in a black scarf and danced for eight hours, until she collapsed; and several of her performances made in collaboration with German artist Ulay, including one where they slam their bodies together, and another where they sit opposite each other and scream.