Sanjay Reddy in Foreign Policy:

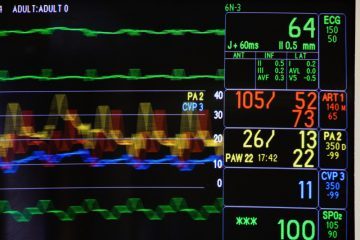

The coronavirus pandemic has dramatically disrupted the everyday social and economic patterns of societies around the world. Economists have focused on its economic impact and on what central banks and governments should do in response to an unusual simultaneous disruption of both supply and demand. There is consensus that governments will have to support businesses and workers who are losing income—or risk dangerous knock-on effects on banks and the real economy—and find a way to finance these expenditures. There is also an urgent need to ramp up the production of essential commodities such as ventilators, gloves, and masks; to provide hospital beds; and to ensure that required personnel can themselves turn up for work. Despite disruption to supply chains and restrictions on the population, essential goods and basic services must be provided, firms must be kept from going bankrupt, and employment and incomes must be maintained.

These circumstances raise fundamental questions about the role of the market and the public sector in doing what is needed on the required scale and with sufficient speed. Some economic thinkers are rightly attacking these problems with urgency. But addressing such practical ends also calls for us to rethink more basic economic ideas. The economics discipline has provided the most influential framework for thinking about public policies, but it has proved inadequate, both in preparing for the current emergency and for dealing with it. The pandemic underlines the necessity for a rethinking of our received ideas about economics and points in some directions that this rethinking should take.

More here.

Alex de Waal in Boston Review:

Alex de Waal in Boston Review: Over at NDPR, Allen Wood reviews Henry Allison’s Kant’s Conception of Freedom: A Developmental and Critical Analysis:

Over at NDPR, Allen Wood reviews Henry Allison’s Kant’s Conception of Freedom: A Developmental and Critical Analysis: What makes My Morningless Mornings so notable, though, is not just the story of a ruminative young person who rejects the thrills associated with teenage life or even the early onset of her adulthood. Golberg’s work also functions as an abstract, winding, and rebellious consideration of the mundane qualities of the day’s earliest hours. Whereas the morning often is referred to as a beginning or a renewal of possibilities, Golberg instead asks her readers to consider it night’s ending and the conclusion of dream-induced wanderings and endless darkness.

What makes My Morningless Mornings so notable, though, is not just the story of a ruminative young person who rejects the thrills associated with teenage life or even the early onset of her adulthood. Golberg’s work also functions as an abstract, winding, and rebellious consideration of the mundane qualities of the day’s earliest hours. Whereas the morning often is referred to as a beginning or a renewal of possibilities, Golberg instead asks her readers to consider it night’s ending and the conclusion of dream-induced wanderings and endless darkness. Two of my favorite essays, by Seamus Perry and Sandra Mayer respectively, offer guided tours of W.H. Auden’s apartment at 77 St. Mark’s Place in New York, where the poet lived between 1954 and 1972, and his late-in-life Kirchstetten house in Austria. Auden famously united minimum attention to his living conditions with maximum regard for routine and order. He wore the same suit day after day, padded around Manhattan in carpet slippers and utilized his kitchen sink as a toilet. Composer Igor Stravinsky called him “the dirtiest man I have ever liked.” Relying on literary journalism to pay his bills, Auden toiled at his desk every day from 9 a.m. till 4 or 5 p.m., then enjoyed a massive cocktail or two, sat down to a well prepared dinner promptly at 6 and toddled off to bed as early as 9:00, sometimes shooing guests out the door. In Austria, the poet acquired a yellow Volkswagen, eventually used as the getaway car in a series of robberies committed by a longtime lover.

Two of my favorite essays, by Seamus Perry and Sandra Mayer respectively, offer guided tours of W.H. Auden’s apartment at 77 St. Mark’s Place in New York, where the poet lived between 1954 and 1972, and his late-in-life Kirchstetten house in Austria. Auden famously united minimum attention to his living conditions with maximum regard for routine and order. He wore the same suit day after day, padded around Manhattan in carpet slippers and utilized his kitchen sink as a toilet. Composer Igor Stravinsky called him “the dirtiest man I have ever liked.” Relying on literary journalism to pay his bills, Auden toiled at his desk every day from 9 a.m. till 4 or 5 p.m., then enjoyed a massive cocktail or two, sat down to a well prepared dinner promptly at 6 and toddled off to bed as early as 9:00, sometimes shooing guests out the door. In Austria, the poet acquired a yellow Volkswagen, eventually used as the getaway car in a series of robberies committed by a longtime lover. The window was sealed behind a sheet of solid steel. The door was locked. Thick chains bound one arm and one ankle. The room was bare apart from a thin foam mat for a bed and a plastic bottle to pee into. I was alone. That was the summer of 1987, when Hizbullah was holding me hostage in Lebanon. They had many other hostages, but I didn’t see them. In fact, I saw no one. When a guard came into the room, I had to put on a blindfold so that I couldn’t identify him. The only conversations I had were a few interrogations, when I was also blindfolded. The questioning involved threats and verbal abuse, but mercifully no torture. As unpleasant as they were, they broke the monotony. The rest of the time left me thinking, remembering, imagining. One way of relieving the loneliness was to pretend that one or another of my children was with me, each on a different day. I made chess pieces out of paper labels on water bottles to play with each one. Sometimes I let them win, or they beat me outright.

The window was sealed behind a sheet of solid steel. The door was locked. Thick chains bound one arm and one ankle. The room was bare apart from a thin foam mat for a bed and a plastic bottle to pee into. I was alone. That was the summer of 1987, when Hizbullah was holding me hostage in Lebanon. They had many other hostages, but I didn’t see them. In fact, I saw no one. When a guard came into the room, I had to put on a blindfold so that I couldn’t identify him. The only conversations I had were a few interrogations, when I was also blindfolded. The questioning involved threats and verbal abuse, but mercifully no torture. As unpleasant as they were, they broke the monotony. The rest of the time left me thinking, remembering, imagining. One way of relieving the loneliness was to pretend that one or another of my children was with me, each on a different day. I made chess pieces out of paper labels on water bottles to play with each one. Sometimes I let them win, or they beat me outright. Thomas Roe, Britain’s envoy in India during the 1620s, wrote of Empress Nur Jehan’s power over her husband, the Mughal emperor Jehangir, that she “governs him, and wynds him up at her pleasure.”

Thomas Roe, Britain’s envoy in India during the 1620s, wrote of Empress Nur Jehan’s power over her husband, the Mughal emperor Jehangir, that she “governs him, and wynds him up at her pleasure.” What sets aside mere tabloid news from a more revelatory scandal that says something about human nature? On this point, I defer to a lesson learned from a wise editor. I had been doing a story for the pioneering journalism-criticism magazine More on a terrific character, New York icon Pat Doyle, homicide reporter for the tabloid Daily News.

What sets aside mere tabloid news from a more revelatory scandal that says something about human nature? On this point, I defer to a lesson learned from a wise editor. I had been doing a story for the pioneering journalism-criticism magazine More on a terrific character, New York icon Pat Doyle, homicide reporter for the tabloid Daily News. To Jonathan Bate, Wordsworth matters principally as a prophet of nature. This may sound like what Basil Fawlty used to call a statement of the bleeding obvious. But in fact, since the Second World War scholars have more often thought about him in other terms: politically, or as a writer about psychological development, or as a central member of the ‘visionary company’ of English Romantics, the watchword for whom was not ‘Nature’ so much as ‘Imagination’. The return of nature to Wordsworthian commentary is a corollary of the environmentalist spirit of the age. The process was largely initiated by Bate himself in a book called Romantic Ecology (1991). This new book resumes the theme, providing a colourfully written celebration (one chapter is entitled ‘Lucy in the Harz with Dorothy’) of Wordsworth’s ‘radical alternative religion of nature’.

To Jonathan Bate, Wordsworth matters principally as a prophet of nature. This may sound like what Basil Fawlty used to call a statement of the bleeding obvious. But in fact, since the Second World War scholars have more often thought about him in other terms: politically, or as a writer about psychological development, or as a central member of the ‘visionary company’ of English Romantics, the watchword for whom was not ‘Nature’ so much as ‘Imagination’. The return of nature to Wordsworthian commentary is a corollary of the environmentalist spirit of the age. The process was largely initiated by Bate himself in a book called Romantic Ecology (1991). This new book resumes the theme, providing a colourfully written celebration (one chapter is entitled ‘Lucy in the Harz with Dorothy’) of Wordsworth’s ‘radical alternative religion of nature’. The deserted streets will fill again, and we will leave our screen-lit burrows blinking with relief. But the world will be different from how we imagined it in what we thought were normal times. This is not a temporary rupture in an otherwise stable equilibrium: the crisis through which we are living is a turning point in history. The era of peak globalisation is over. An economic system that relied on worldwide production and long supply chains is morphing into one that will be less interconnected. A way of life driven by unceasing mobility is shuddering to a stop. Our lives are going to be more physically constrained and more virtual than they were. A more fragmented world is coming into being that in some ways may be more resilient.

The deserted streets will fill again, and we will leave our screen-lit burrows blinking with relief. But the world will be different from how we imagined it in what we thought were normal times. This is not a temporary rupture in an otherwise stable equilibrium: the crisis through which we are living is a turning point in history. The era of peak globalisation is over. An economic system that relied on worldwide production and long supply chains is morphing into one that will be less interconnected. A way of life driven by unceasing mobility is shuddering to a stop. Our lives are going to be more physically constrained and more virtual than they were. A more fragmented world is coming into being that in some ways may be more resilient. Do you find it as obvious as I do that Don DeLillo richly deserves to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature? And right away, as in this year?

Do you find it as obvious as I do that Don DeLillo richly deserves to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature? And right away, as in this year? Philip W. Anderson speaks in a slow, deliberate growl, pausing between sentences to ponder his next move. His basal expression, too, is deadpan. But like some exotic ceramic in an unstable state, Anderson’s mood can flip in an instant between different modes.

Philip W. Anderson speaks in a slow, deliberate growl, pausing between sentences to ponder his next move. His basal expression, too, is deadpan. But like some exotic ceramic in an unstable state, Anderson’s mood can flip in an instant between different modes. When Neil Ferguson visited the heart of British government in London’s Downing Street, he was much closer to the COVID-19 pandemic than he realized. Ferguson, a mathematical epidemiologist at Imperial College London, briefed officials in mid-March on the latest results of his team’s computer models, which simulated the rapid spread of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 through the UK population. Less than 36 hours later, he announced on Twitter that he had a fever and a cough. A positive test followed. The disease-tracking scientist had become a data point in his own project. Ferguson is one of the highest-profile faces in the effort to use mathematical models that predict the spread of the virus — and that show how government actions could alter the course of the outbreak. “It’s been an immensely intensive and exhausting few months,” says Ferguson, who kept working throughout his relatively mild symptoms of COVID-19. “I haven’t really had a day off since mid-January.”

When Neil Ferguson visited the heart of British government in London’s Downing Street, he was much closer to the COVID-19 pandemic than he realized. Ferguson, a mathematical epidemiologist at Imperial College London, briefed officials in mid-March on the latest results of his team’s computer models, which simulated the rapid spread of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 through the UK population. Less than 36 hours later, he announced on Twitter that he had a fever and a cough. A positive test followed. The disease-tracking scientist had become a data point in his own project. Ferguson is one of the highest-profile faces in the effort to use mathematical models that predict the spread of the virus — and that show how government actions could alter the course of the outbreak. “It’s been an immensely intensive and exhausting few months,” says Ferguson, who kept working throughout his relatively mild symptoms of COVID-19. “I haven’t really had a day off since mid-January.”

Being neither alive nor dead, nor even simply inert, a virus makes a bad enemy. How do you confront it? “We are at war,” politicians keep saying. But unlike a political opponent, the viral enemy can’t be banished or killed, or even really defeated. A virus is a vector, a force that we can only amplify or disrupt.

Being neither alive nor dead, nor even simply inert, a virus makes a bad enemy. How do you confront it? “We are at war,” politicians keep saying. But unlike a political opponent, the viral enemy can’t be banished or killed, or even really defeated. A virus is a vector, a force that we can only amplify or disrupt.