Rafia Zakaria in The New York Times:

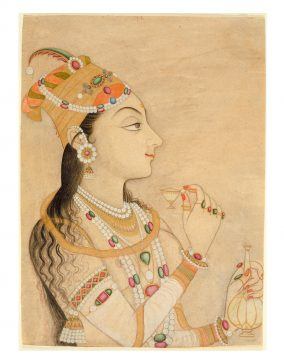

Thomas Roe, Britain’s envoy in India during the 1620s, wrote of Empress Nur Jehan’s power over her husband, the Mughal emperor Jehangir, that she “governs him, and wynds him up at her pleasure.”

Thomas Roe, Britain’s envoy in India during the 1620s, wrote of Empress Nur Jehan’s power over her husband, the Mughal emperor Jehangir, that she “governs him, and wynds him up at her pleasure.”

The story of Nur Jehan, who was born to migrant parents and rose to a position where she unofficially ruled jointly with her husband, is just one of the intriguing tales that make up Hossein Kamaly’s eminently readable collection “A History of Islam in 21 Women.” Besides Nur Jehan, we hear of the Prophet Muhammad’s wife Khadija, who saw the promise of an orphaned young man and was the first to accept Islam, and the Sufi ascetic Rabia Al-Adawiyya, who insisted that women were the spiritual equals of men. Later on came the Yemeni queen Arwa, who ruled for seven decades and even issued coinage in her own name, and also Noor Inayat Khan, the Sufi-Muslim British spy who went into Nazi-occupied France to radio enemy movements back to Britain.

Indeed, the Muslim women recounted by Kamaly (who teaches Islamic studies at Hartford Seminary) are a feisty and intrepid bunch. Collectively, they constitute a foil against the persistent myth that Muslim women are simpering sorts awaiting rescue. This Western “rescue” fantasy and the would-be saviors it creates were duly debunked by the Columbia professor Lila Abu-Lughod in her book “Do Muslim Women Need Saving?” But while Abu-Lughod’s work provides a theoretical critique of Western insouciance and obstinacy in holding on to the myth of Muslim helplessness, Kamaly’s book hands up the lived examples. Here in all their gutsy glory are women whose voices have not received the prominence that is their due within the story of Islam.

More here.