Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

If one of the ambitious goals of philosophy is to determine the meaning of life, one of the ambitious goals of psychology is to tell us how to achieve it. An influential work in this direction was Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs — a list of human needs, often displayed suggestively in the form of a pyramid, ranging from the most basic (food and shelter) to the most refined. At the top lurks “self-actualization,” the ultimate goal of achieving one’s creative capacities. Psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman has elaborated on this model, both by exploring less-well-known writings of Maslow’s, and also by incorporating more recent empirical psychological studies. He suggests the more dynamical metaphor of a sailboat, where the hull represents basic security needs and the sail more creative and dynamical capabilities. It’s an interesting take on the importance of appreciating that the nature of our lives is one of constant flux.

If one of the ambitious goals of philosophy is to determine the meaning of life, one of the ambitious goals of psychology is to tell us how to achieve it. An influential work in this direction was Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs — a list of human needs, often displayed suggestively in the form of a pyramid, ranging from the most basic (food and shelter) to the most refined. At the top lurks “self-actualization,” the ultimate goal of achieving one’s creative capacities. Psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman has elaborated on this model, both by exploring less-well-known writings of Maslow’s, and also by incorporating more recent empirical psychological studies. He suggests the more dynamical metaphor of a sailboat, where the hull represents basic security needs and the sail more creative and dynamical capabilities. It’s an interesting take on the importance of appreciating that the nature of our lives is one of constant flux.

More here.

Katherine Scott Nelson’s extraordinary essay, “Dinner and a Fight,” recounts their past experience in the gig economy, working as a waiter and bartender at catering events in the Chicago area. It’s an insecure life of low pay, no insurance (though injuries lurk around every corner), and no future. Compounding these difficulties, Nelson, who is a nonbinary trans person pursuing gender transition, worked in a business where male and female boundaries are carefully marked. Yet throughout this essay Nelson displays a can-do brio, a stubborn slogging bravery, and even humor, which adds poignancy to the march of one grinding day after another. In these sudden, terrifying days of the coronavirus pandemic, the lives of the people you will read about here have become even more precarious, as our country’s shameful economic and healthcare inequality worsens in the crisis. —Philip Graham

Katherine Scott Nelson’s extraordinary essay, “Dinner and a Fight,” recounts their past experience in the gig economy, working as a waiter and bartender at catering events in the Chicago area. It’s an insecure life of low pay, no insurance (though injuries lurk around every corner), and no future. Compounding these difficulties, Nelson, who is a nonbinary trans person pursuing gender transition, worked in a business where male and female boundaries are carefully marked. Yet throughout this essay Nelson displays a can-do brio, a stubborn slogging bravery, and even humor, which adds poignancy to the march of one grinding day after another. In these sudden, terrifying days of the coronavirus pandemic, the lives of the people you will read about here have become even more precarious, as our country’s shameful economic and healthcare inequality worsens in the crisis. —Philip Graham At the Mildura Writer’s Festival in 2019, on a panel with Craig Sherborne and Moreno Giovannoni, Helen Garner spoke about Raymond Carver’s unedited stories. She hated them for all of their sentimental scenes—ones that would be removed by Carver’s editor Gordon Lish for What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Lish took a knife to the cushy scenes and Carver became a master of the spare and cutting. When we arrived home from the festival, my partner and I compared the un-edited stories in Beginners with their edited counter-parts in What we Talk About. For a long time, I had preferred the un-edited versions, yet it had been at least six years since I last read through the stories. We sat on the couch, looking for differences, reading them aloud and deciding which version was better. Garner was right—in What We Talk About large sections of emotive description are gone and, when characters are presented under a harsh light, their crudest actions can leave the reader with sharper impressions of their personality.

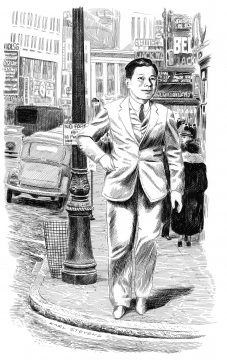

At the Mildura Writer’s Festival in 2019, on a panel with Craig Sherborne and Moreno Giovannoni, Helen Garner spoke about Raymond Carver’s unedited stories. She hated them for all of their sentimental scenes—ones that would be removed by Carver’s editor Gordon Lish for What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Lish took a knife to the cushy scenes and Carver became a master of the spare and cutting. When we arrived home from the festival, my partner and I compared the un-edited stories in Beginners with their edited counter-parts in What we Talk About. For a long time, I had preferred the un-edited versions, yet it had been at least six years since I last read through the stories. We sat on the couch, looking for differences, reading them aloud and deciding which version was better. Garner was right—in What We Talk About large sections of emotive description are gone and, when characters are presented under a harsh light, their crudest actions can leave the reader with sharper impressions of their personality. The Killing ends with the greatest money shot in the movies, its nearest competition being the shower of love bestowed on James Stewart on Christmas Eve at the end of It’s A Wonderful Life. Johnny and Fay are at the airport about to board a flight to Boston and freedom. He doesn’t want to let go of the suitcase, but it is too big for the overhead compartment, so he reluctantly yields it. He and Fay watch the suitcase totter atop the checked luggage in the cart taking it from terminal to plane. When a spectator’s dog runs into the cart’s path, the driver swerves, and the suitcase falls off. It pops opens, and the money flies around like snow in a swirling wind.

The Killing ends with the greatest money shot in the movies, its nearest competition being the shower of love bestowed on James Stewart on Christmas Eve at the end of It’s A Wonderful Life. Johnny and Fay are at the airport about to board a flight to Boston and freedom. He doesn’t want to let go of the suitcase, but it is too big for the overhead compartment, so he reluctantly yields it. He and Fay watch the suitcase totter atop the checked luggage in the cart taking it from terminal to plane. When a spectator’s dog runs into the cart’s path, the driver swerves, and the suitcase falls off. It pops opens, and the money flies around like snow in a swirling wind.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the 18th-century poet and philosopher, believed life was hardwired with archetypes, or models, which instructed its development. Yet he was fascinated with how life could, at the same time, be so malleable. One day, while meditating on a leaf, the poet had what you might call a proto-evolutionary thought: Plants were never created “and then locked into the given form” but have instead been given, he later wrote, a “felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.” A rediscovery of principles of genetic inheritance in the early 20th century showed that organisms could not learn or acquire heritable traits by interacting with their environment, but they did not yet explain how life could undergo such shapeshifting tricks—the plasticity that fascinated Goethe.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the 18th-century poet and philosopher, believed life was hardwired with archetypes, or models, which instructed its development. Yet he was fascinated with how life could, at the same time, be so malleable. One day, while meditating on a leaf, the poet had what you might call a proto-evolutionary thought: Plants were never created “and then locked into the given form” but have instead been given, he later wrote, a “felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.” A rediscovery of principles of genetic inheritance in the early 20th century showed that organisms could not learn or acquire heritable traits by interacting with their environment, but they did not yet explain how life could undergo such shapeshifting tricks—the plasticity that fascinated Goethe.

Fear sweeps the land. Many businesses collapse. Some huge fortunes are made. Panicked consumers stockpile paper, food, and weapons. The government’s reaction is inconsistent and ineffectual. Ordinary commerce grinds to a halt; investors can find no safe assets. Political factionalism grows more intense. Everything falls apart. This was all as true of revolutionary France in 1789 and 1790 as it is of the United States today. Are we at the beginning of a revolution that has yet to be named? Do we want to be? That we are on the verge of a major transformation seems obvious. The onset of the next Depression, a challenge akin to World War II, a

Fear sweeps the land. Many businesses collapse. Some huge fortunes are made. Panicked consumers stockpile paper, food, and weapons. The government’s reaction is inconsistent and ineffectual. Ordinary commerce grinds to a halt; investors can find no safe assets. Political factionalism grows more intense. Everything falls apart. This was all as true of revolutionary France in 1789 and 1790 as it is of the United States today. Are we at the beginning of a revolution that has yet to be named? Do we want to be? That we are on the verge of a major transformation seems obvious. The onset of the next Depression, a challenge akin to World War II, a  Over at the NYRB Blog, Ali Bhutto, Jamie Quatro, Edward Stephens, Carl Elliott, and Liza Batkin, et al.:

Over at the NYRB Blog, Ali Bhutto, Jamie Quatro, Edward Stephens, Carl Elliott, and Liza Batkin, et al.: Omar Shaban in Counterpunch:

Omar Shaban in Counterpunch: