Holland Cotter in The New York Times:

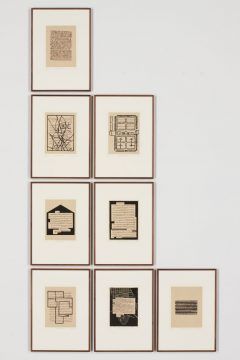

Ms. Hashmi, who preferred to identify herself professionally by only her first name, became internationally known for woodcuts and intaglio prints, many combining semiabstract images of houses and cities she had lived in accompanied by inscriptions written in Urdu, a language spoken primarily by Muslim South Asians. (It is the official national language of Pakistan.) In South Asia itself, she is particularly revered as a representative of a now-vanishing generation of artists who were alive during the 1947 partition of the subcontinent along ethnic and religious lines, a catastrophic event that, she felt, cut her loose from her roots and haunted her life and work. Zarina Rashid was born on July 16, 1937, the youngest of five children, in the small Indian town of Aligarh, where her father, Sheikh Abdur Rashid, taught at Aligarh Muslim University. Her mother, Fahmida Begum, was a homemaker. In her 2018 memoir, “Directions to My House,” Ms. Hashmi described growing up in what she called a traditional Muslim home. In hot months she and her older sister Rani would sleep outdoors “under the stars and plot our journeys in life.” The floor plan of her childhood house, whose walls enclosed a fragrant garden, became a recurrent presence in her art. That life abruptly ended with the partition of India and the violence between Muslims and Hindus. For safety, her father sent the family to Karachi in the newly formed Pakistan. The experience of fleeing to a refugee camp and seeing bodies left in the road stayed with Ms. Hashmi. “These memories formed how I think about a lot of things: fear, separation, migration, the people you know, or think you know,” she wrote in her memoir.

Ms. Hashmi, who preferred to identify herself professionally by only her first name, became internationally known for woodcuts and intaglio prints, many combining semiabstract images of houses and cities she had lived in accompanied by inscriptions written in Urdu, a language spoken primarily by Muslim South Asians. (It is the official national language of Pakistan.) In South Asia itself, she is particularly revered as a representative of a now-vanishing generation of artists who were alive during the 1947 partition of the subcontinent along ethnic and religious lines, a catastrophic event that, she felt, cut her loose from her roots and haunted her life and work. Zarina Rashid was born on July 16, 1937, the youngest of five children, in the small Indian town of Aligarh, where her father, Sheikh Abdur Rashid, taught at Aligarh Muslim University. Her mother, Fahmida Begum, was a homemaker. In her 2018 memoir, “Directions to My House,” Ms. Hashmi described growing up in what she called a traditional Muslim home. In hot months she and her older sister Rani would sleep outdoors “under the stars and plot our journeys in life.” The floor plan of her childhood house, whose walls enclosed a fragrant garden, became a recurrent presence in her art. That life abruptly ended with the partition of India and the violence between Muslims and Hindus. For safety, her father sent the family to Karachi in the newly formed Pakistan. The experience of fleeing to a refugee camp and seeing bodies left in the road stayed with Ms. Hashmi. “These memories formed how I think about a lot of things: fear, separation, migration, the people you know, or think you know,” she wrote in her memoir.

…Near-abstract images of houses recurred. A 1981 cast-paper relief called “Homecoming” is essentially an aerial view of a courtyard surrounded by arches, reminiscent of the one in her childhood home. A bronze sculpture, “I Went on a Journey III” (1991), is a miniature house on wheels. The prints in a portfolio called “Homes I Made/A Life in Nine Lines” are based on blueprints of houses that Ms. Hashmi had lived in from 1958 onward. And in a print series called “Letters From Home,” Ms. Hashmi overlaid images of both house and city onto the texts of letters, often about family deaths and loss, that her sister Rani had written to her but never sent. Significantly, each letter is transcribed in Urdu script, as are many identifying labels in other prints. Urdu is slowly going out of currency in sectarian India, but for Ms. Hashmi it defined “home” as surely as images of maps and houses did. “The biggest loss for me is language,” she told Ms. Stewart. “Specifically poetry. Before I go to bed lately, thanks to YouTube, I listen to the recitation of poetry in Urdu. I jokingly say I have lived a life in translation.”

More here.

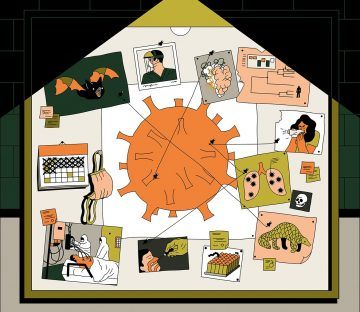

In 1912, German veterinarians puzzled over the case of a feverish cat with an enormously swollen belly. That is now thought to be the first reported example of the debilitating power of a coronavirus. Veterinarians didn’t know it at the time, but coronaviruses were also giving chickens bronchitis, and pigs an intestinal disease that killed almost every piglet under two weeks old. The link between these pathogens remained hidden until the 1960s, when researchers in the United Kingdom and the United States isolated two viruses with crown-like structures causing common colds in humans. Scientists soon noticed that the viruses identified in sick animals had the same bristly structure, studded with spiky protein protrusions. Under electron microscopes, these viruses resembled the solar corona, which led researchers in 1968 to coin the term coronaviruses for the entire group. It was a family of dynamic killers: dog coronaviruses could harm cats, the cat coronavirus could ravage pig intestines. Researchers thought that coronaviruses caused only mild symptoms in humans, until the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 revealed how easily these versatile viruses could kill people.

In 1912, German veterinarians puzzled over the case of a feverish cat with an enormously swollen belly. That is now thought to be the first reported example of the debilitating power of a coronavirus. Veterinarians didn’t know it at the time, but coronaviruses were also giving chickens bronchitis, and pigs an intestinal disease that killed almost every piglet under two weeks old. The link between these pathogens remained hidden until the 1960s, when researchers in the United Kingdom and the United States isolated two viruses with crown-like structures causing common colds in humans. Scientists soon noticed that the viruses identified in sick animals had the same bristly structure, studded with spiky protein protrusions. Under electron microscopes, these viruses resembled the solar corona, which led researchers in 1968 to coin the term coronaviruses for the entire group. It was a family of dynamic killers: dog coronaviruses could harm cats, the cat coronavirus could ravage pig intestines. Researchers thought that coronaviruses caused only mild symptoms in humans, until the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 revealed how easily these versatile viruses could kill people. Unless you have studied philosophy, maths or economics, it is unlikely you have heard of Frank Ramsey. And if you have, it is probably as a minor character in stories about his celebrated Cambridge philosophical contemporaries Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Unless you have studied philosophy, maths or economics, it is unlikely you have heard of Frank Ramsey. And if you have, it is probably as a minor character in stories about his celebrated Cambridge philosophical contemporaries Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Everybody talks about the truth, but nobody does anything about it. And to be honest, how we talk about truth — what it is, and how to get there — can be a little sloppy at times. Philosophy to the rescue! I had a very ambitious conversation with Liam Kofi Bright, starting with what we mean by “truth” (correspondence, coherence, pragmatist, and deflationary approaches), and then getting into the nitty-gritty of how we actually discover it. There’s a lot to think about once we take a hard look at how science gets done, how discoveries are communicated, and what different kinds of participants can bring to the table.

Everybody talks about the truth, but nobody does anything about it. And to be honest, how we talk about truth — what it is, and how to get there — can be a little sloppy at times. Philosophy to the rescue! I had a very ambitious conversation with Liam Kofi Bright, starting with what we mean by “truth” (correspondence, coherence, pragmatist, and deflationary approaches), and then getting into the nitty-gritty of how we actually discover it. There’s a lot to think about once we take a hard look at how science gets done, how discoveries are communicated, and what different kinds of participants can bring to the table.

Among the many mysteries that remain about COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, is why it hits some people harder than others. Millions of people have been infected, but many never get sick. Those who do can experience an ever-expanding array of symptoms, including loss of smell or taste, pink eye, digestive issues, fever, cough, and difficulty breathing. Although the elderly, those with pre-existing conditions such as heart disease, and

Among the many mysteries that remain about COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, is why it hits some people harder than others. Millions of people have been infected, but many never get sick. Those who do can experience an ever-expanding array of symptoms, including loss of smell or taste, pink eye, digestive issues, fever, cough, and difficulty breathing. Although the elderly, those with pre-existing conditions such as heart disease, and  More than once recently, I have lain awake counting the sirens going up the otherwise empty streets of Manhattan, wondering if their number might serve as a metric for how bad the coming day would be. But I know that none of my days could approach what Adm. Richard E. Byrd, the American arctic explorer, endured in 1934, when he spent five months alone in a one-room shack in Antarctica, wintering over the long night. January 2020 was the 200th anniversary of the first sighting of Antarctica, by Russian sailors. Byrd’s account of his 1934 ordeal, “Alone,” published in 1938, has been sitting by my bedside; call it the ultimate experiment in social distancing. At the time, Byrd was already famous for having been the first person to fly over the North Pole (although some researchers have disputed that claim) and, later, over the South Pole. He had received three ticker tape parades on Broadway. “My footless habits were practically ruinous to those who had to live with me,” he wrote. “Remembering the way it all was, I still wonder how my wife succeeded in bringing up four such splendid children as ours, wise each in his or her way.”

More than once recently, I have lain awake counting the sirens going up the otherwise empty streets of Manhattan, wondering if their number might serve as a metric for how bad the coming day would be. But I know that none of my days could approach what Adm. Richard E. Byrd, the American arctic explorer, endured in 1934, when he spent five months alone in a one-room shack in Antarctica, wintering over the long night. January 2020 was the 200th anniversary of the first sighting of Antarctica, by Russian sailors. Byrd’s account of his 1934 ordeal, “Alone,” published in 1938, has been sitting by my bedside; call it the ultimate experiment in social distancing. At the time, Byrd was already famous for having been the first person to fly over the North Pole (although some researchers have disputed that claim) and, later, over the South Pole. He had received three ticker tape parades on Broadway. “My footless habits were practically ruinous to those who had to live with me,” he wrote. “Remembering the way it all was, I still wonder how my wife succeeded in bringing up four such splendid children as ours, wise each in his or her way.” Patrick Heller in The Hindu:

Patrick Heller in The Hindu:

Over the past

Over the past A bewildering beginning. A German man has a dream that his wife is cheating on him. He wakes up enraged and boards a flight to Tokyo. Why? He has no idea. Arriving in Tokyo, he encounters a young man trying to commit suicide. The German man, Gilbert Silvester, is an adjunct professor, specialising in the religious significance of beards in art and film. Because of his occupation, he can’t help but notice the young man standing precariously on the edge of the train station platform ‑ not because the young man seems in peril but because he has prominent facial hair, something Gilbert did not expect to find in Japan. Striking up a conversation, he learns that the young man is trying to commit suicide. To distract him, Gilbert suggests a trip to find a more poetic place to die. And so, this odd couple embark on a journey north to Matsushima.

A bewildering beginning. A German man has a dream that his wife is cheating on him. He wakes up enraged and boards a flight to Tokyo. Why? He has no idea. Arriving in Tokyo, he encounters a young man trying to commit suicide. The German man, Gilbert Silvester, is an adjunct professor, specialising in the religious significance of beards in art and film. Because of his occupation, he can’t help but notice the young man standing precariously on the edge of the train station platform ‑ not because the young man seems in peril but because he has prominent facial hair, something Gilbert did not expect to find in Japan. Striking up a conversation, he learns that the young man is trying to commit suicide. To distract him, Gilbert suggests a trip to find a more poetic place to die. And so, this odd couple embark on a journey north to Matsushima. Propaganda also

Propaganda also The modern world has been shaped by the belief that humans can outsmart and defeat death. That was a revolutionary new attitude. For most of history, humans meekly submitted to death. Up to the late modern age, most religions and ideologies saw death not only as our inevitable fate, but as the main source of meaning in life. The most important events of human existence happened after you exhaled your last breath. Only then did you come to learn the true secrets of life. Only then did you gain eternal salvation, or suffer everlasting damnation. In a world without death – and therefore without heaven, hell or reincarnation – religions such as Christianity, Islam and Hinduism would have made no sense. For most of history the best human minds were busy giving meaning to death, not trying to defeat it. The

The modern world has been shaped by the belief that humans can outsmart and defeat death. That was a revolutionary new attitude. For most of history, humans meekly submitted to death. Up to the late modern age, most religions and ideologies saw death not only as our inevitable fate, but as the main source of meaning in life. The most important events of human existence happened after you exhaled your last breath. Only then did you come to learn the true secrets of life. Only then did you gain eternal salvation, or suffer everlasting damnation. In a world without death – and therefore without heaven, hell or reincarnation – religions such as Christianity, Islam and Hinduism would have made no sense. For most of history the best human minds were busy giving meaning to death, not trying to defeat it. The  When the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi announced to his parents, secular Hindus, that he planned to convert to Buddhism and ordain as a monk, his father convened 76 members of his extended family to discuss the matter. Over several hours his relatives plied him with questions, an ordeal Priyadarshi calls “trial by family” in his memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, coauthored by Zara Houshmand. To understand his parents’ severe reaction, it helps to know that at the time of the interrogation Priyadarshi was only 10 years old. He had just run away from boarding school in West Bengal, India, and vanished without a trace. His family had spent two anguished weeks trying to locate him and finally tracked him down at a Japanese Buddhist temple in Bihar, nearly 300 kilometers from the school where he was supposed to be. At that moment, they were not feeling very sympathetic.

When the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi announced to his parents, secular Hindus, that he planned to convert to Buddhism and ordain as a monk, his father convened 76 members of his extended family to discuss the matter. Over several hours his relatives plied him with questions, an ordeal Priyadarshi calls “trial by family” in his memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, coauthored by Zara Houshmand. To understand his parents’ severe reaction, it helps to know that at the time of the interrogation Priyadarshi was only 10 years old. He had just run away from boarding school in West Bengal, India, and vanished without a trace. His family had spent two anguished weeks trying to locate him and finally tracked him down at a Japanese Buddhist temple in Bihar, nearly 300 kilometers from the school where he was supposed to be. At that moment, they were not feeling very sympathetic.