Samuel Clowes Huneke in the Boston Review:

Last Thursday, Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman issued a warning in the New York Times. “The pandemic will eventually end,” he wrote, “but democracy, once lost, may never come back. And we’re much closer to losing our democracy than many people realize.” Citing the Wisconsin election debacle—the Supreme Court ruled that voters would have to vote in person, risking their health—Krugman argued that Donald Trump and the Republican Party are using the crisis for their own, authoritarian ends.

Last Thursday, Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman issued a warning in the New York Times. “The pandemic will eventually end,” he wrote, “but democracy, once lost, may never come back. And we’re much closer to losing our democracy than many people realize.” Citing the Wisconsin election debacle—the Supreme Court ruled that voters would have to vote in person, risking their health—Krugman argued that Donald Trump and the Republican Party are using the crisis for their own, authoritarian ends.

Krugman is not alone. As early as last month, when cases of COVID-19 first began to surge in the United States, Masha Gessen wrote in the New Yorker that the virus was fueling “Trump’s autocratic instincts.” They argued, “We have long known that Trump has totalitarian instincts . . . the coronavirus has brought us a step closer.” This is indeed the once and future critique of the Trump presidency: that Trump is a totalitarian at heart and, if given the chance, “would want to establish total control over a mobilized society.” A few days ago, Salon published an article arguing that the president is using the virus to prepare “the ground for a totalitarian dictatorship.” Even Meghan McCain, as unlikely a person as any to agree with Gessen, indicated recently that Trump has “always been a sort of totalitarian president” and that he might use the virus to “play on the American public’s fears in a draconian way and possibly do something akin to the Patriot Act.”

These critiques make ample use of the term totalitarianism—“that most horrible of inventions of the twentieth century,” in Gessen’s summation. They and other commentators also use it to describe Fidel Castro’s Cuba to Vladimir Putin’s Russia, which Gessen left in 2013. As right-wing populism has surged around the world in recent years, the term has had something of a renaissance. Hannah Arendt’s 1951 classic The Origins of Totalitarianism became a best seller again after Donald Trump’s election in November 2016.

This uptick in the term’s use runs counter to the trend among historians, for whom the idea of totalitarianism carries increasingly little weight.

More here.

Artificial intelligence has made great strides of late, in areas as diverse as playing Go and recognizing pictures of dogs. We still seem to be a ways away from AI that is intelligent in the human sense, but it might not be too long before we have to start thinking seriously about the “motivations” and “purposes” of artificial agents. Stuart Russell is a longtime expert in AI, and he takes extremely seriously the worry that these motivations and purposes may be dramatically at odds with our own. In his book Human Compatible, Russell suggests that the secret is to give up on building our own goals into computers, and rather programming them to figure out our goals by actually observing how humans behave.

Artificial intelligence has made great strides of late, in areas as diverse as playing Go and recognizing pictures of dogs. We still seem to be a ways away from AI that is intelligent in the human sense, but it might not be too long before we have to start thinking seriously about the “motivations” and “purposes” of artificial agents. Stuart Russell is a longtime expert in AI, and he takes extremely seriously the worry that these motivations and purposes may be dramatically at odds with our own. In his book Human Compatible, Russell suggests that the secret is to give up on building our own goals into computers, and rather programming them to figure out our goals by actually observing how humans behave. The room is perhaps the fundamental element of any architecture. As a primitive hut, a simple shelter, a cave or a retreat, the room commands a unique and unrepeatable definition of a place. Making room means to clear a space for oneself: to identify a limit between inside and outside (room, from the proto-Indoeuropean root reue-“to open, space”). Like organs in a body, specific arrangements of rooms correspond to species of buildings with distinctive characteristics. Despite its concatenations, a room always preserves the possibility of autonomy, as a stand-alone entity. In the Western classical tradition—from Vitruvius to Alberti and Palladio—rooms are usually categorized according to forms accurately proportioned to their fulfilled functions.

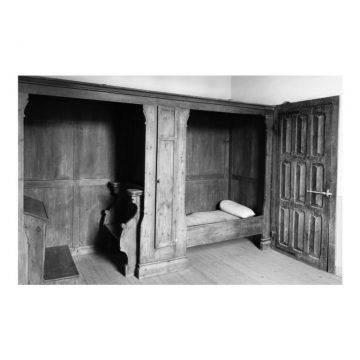

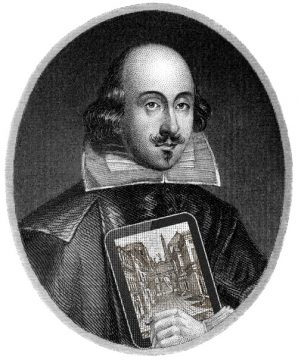

The room is perhaps the fundamental element of any architecture. As a primitive hut, a simple shelter, a cave or a retreat, the room commands a unique and unrepeatable definition of a place. Making room means to clear a space for oneself: to identify a limit between inside and outside (room, from the proto-Indoeuropean root reue-“to open, space”). Like organs in a body, specific arrangements of rooms correspond to species of buildings with distinctive characteristics. Despite its concatenations, a room always preserves the possibility of autonomy, as a stand-alone entity. In the Western classical tradition—from Vitruvius to Alberti and Palladio—rooms are usually categorized according to forms accurately proportioned to their fulfilled functions. William Gass has written of the book’s “terminological greed,” a phrase that goes some way in preparing the reader for The Anatomy’s extraordinary surfeit. Burton the anatomist reaches us as a thoroughly modern figure, a gathering of vibrant and contradictory energies. He is a model of inconsistency, equally at home in sense and nonsense, science and superstition, asceticism and sensuality. He apologizes for the length of his digressions only to plunge into yet more. The resultant overgrowth of text is a sort of radiant miscellany; an accumulation of conjecture, proof, rumor, and heresy; endless lists of proper names, foods, herbs, symptoms, profligate et ceteras, disputations, and lengthy essays within essays. Though not itself a novel, Burton’s fabulous act of literary excess prefigures the encyclopedic postwar fictions of the twentieth century—Gravity’s Rainbow, J R, Underworld—in which poetics and technics came together to approximate the informational density of culture.

William Gass has written of the book’s “terminological greed,” a phrase that goes some way in preparing the reader for The Anatomy’s extraordinary surfeit. Burton the anatomist reaches us as a thoroughly modern figure, a gathering of vibrant and contradictory energies. He is a model of inconsistency, equally at home in sense and nonsense, science and superstition, asceticism and sensuality. He apologizes for the length of his digressions only to plunge into yet more. The resultant overgrowth of text is a sort of radiant miscellany; an accumulation of conjecture, proof, rumor, and heresy; endless lists of proper names, foods, herbs, symptoms, profligate et ceteras, disputations, and lengthy essays within essays. Though not itself a novel, Burton’s fabulous act of literary excess prefigures the encyclopedic postwar fictions of the twentieth century—Gravity’s Rainbow, J R, Underworld—in which poetics and technics came together to approximate the informational density of culture. Many countries are enduring the Hammer today: a heavy set of social distancing measures that have stopped the economy. Millions have lost their jobs, their income, their savings, their businesses, their freedom. The economic cost is brutal. Countries are desperate to know what they need to do to open up the economy again.

Many countries are enduring the Hammer today: a heavy set of social distancing measures that have stopped the economy. Millions have lost their jobs, their income, their savings, their businesses, their freedom. The economic cost is brutal. Countries are desperate to know what they need to do to open up the economy again. The Club: no literary club has ever equaled the one founded in London in 1764 by Samuel Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith, and a handful of others, and which came to include the very brightest intellectual, artistic and political stars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Leo Damrosch provided a close study of the Club, its members, and its doings during the first couple of decades of its long life (it still exists today), in a book I reviewed in The Hudson Review’s

The Club: no literary club has ever equaled the one founded in London in 1764 by Samuel Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith, and a handful of others, and which came to include the very brightest intellectual, artistic and political stars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Leo Damrosch provided a close study of the Club, its members, and its doings during the first couple of decades of its long life (it still exists today), in a book I reviewed in The Hudson Review’s  At 4:18 a.m. on February 1, 1997, a fire broke out in the Aisin Seiki company’s Factory No. 1, in Kariya, a hundred and sixty miles southwest of Tokyo. Soon, flames had engulfed the plant and incinerated the production line that made a part called a P-valve—a device used in vehicles to modulate brake pressure and prevent skidding. The valve was small and cheap—about the size of a fist, and roughly ten dollars apiece—but indispensable. The Aisin factory normally produced almost thirty-three thousand valves a day, and was, at the time, the exclusive supplier of the part for the Toyota Motor Corporation. Within hours, the magnitude of the loss was evident to Toyota. The company had adopted “just in time” (J.I.T.) production: parts, such as P-valves, were produced according to immediate needs—to precisely match the number of vehicles ready for assembly—rather than sitting around in stockpiles. But the fire had now put the whole enterprise at risk: with no inventory in the warehouse, there were only enough valves to last a single day. The production of all Toyota vehicles was about to grind to a halt. “Such is the fragility of JIT: a surprise event can paralyze entire networks and even industries,” the management scholars Toshihiro Nishiguchi and Alexandre Beaudet observed the following year, in a case study of the episode.

At 4:18 a.m. on February 1, 1997, a fire broke out in the Aisin Seiki company’s Factory No. 1, in Kariya, a hundred and sixty miles southwest of Tokyo. Soon, flames had engulfed the plant and incinerated the production line that made a part called a P-valve—a device used in vehicles to modulate brake pressure and prevent skidding. The valve was small and cheap—about the size of a fist, and roughly ten dollars apiece—but indispensable. The Aisin factory normally produced almost thirty-three thousand valves a day, and was, at the time, the exclusive supplier of the part for the Toyota Motor Corporation. Within hours, the magnitude of the loss was evident to Toyota. The company had adopted “just in time” (J.I.T.) production: parts, such as P-valves, were produced according to immediate needs—to precisely match the number of vehicles ready for assembly—rather than sitting around in stockpiles. But the fire had now put the whole enterprise at risk: with no inventory in the warehouse, there were only enough valves to last a single day. The production of all Toyota vehicles was about to grind to a halt. “Such is the fragility of JIT: a surprise event can paralyze entire networks and even industries,” the management scholars Toshihiro Nishiguchi and Alexandre Beaudet observed the following year, in a case study of the episode. Before 2015, few people would have thought of not finishing college as a public-health issue. That changed because of research done by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, economists at Princeton who are also married. For the past six years, they have been collaboratively researching an alarming long-term increase in what they call “deaths of despair” — suicides, drug overdoses, and alcoholism-related illnesses — among white non-Hispanic Americans without a bachelor’s degree in middle age.

Before 2015, few people would have thought of not finishing college as a public-health issue. That changed because of research done by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, economists at Princeton who are also married. For the past six years, they have been collaboratively researching an alarming long-term increase in what they call “deaths of despair” — suicides, drug overdoses, and alcoholism-related illnesses — among white non-Hispanic Americans without a bachelor’s degree in middle age. By the last week of January, Rob DeLeo knew it was going to get bad.

By the last week of January, Rob DeLeo knew it was going to get bad. The Covid-19 lockdown on the largest population on earth with the shortest possible notice has completed five weeks. Overnight, a medical pandemic was made into an economic and humanitarian disaster of immense proportions. It is time we took stock.

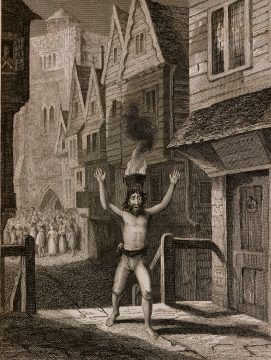

The Covid-19 lockdown on the largest population on earth with the shortest possible notice has completed five weeks. Overnight, a medical pandemic was made into an economic and humanitarian disaster of immense proportions. It is time we took stock. ISTANBUL — For the past four years I have been writing a historical novel set in 1901 during what is known as the third plague pandemic, an outbreak of bubonic plague that killed millions of people in Asia but not very many in Europe. Over the last two months, friends and family, editors and journalists who know the subject of that novel, “Nights of Plague,” have been asking me a barrage of questions about pandemics. They are most curious about similarities between the current coronavirus pandemic and the historical outbreaks of plague and cholera. There is an overabundance of similarities. Throughout human and literary history what makes pandemics alike is not mere commonality of germs and viruses but that our initial responses were always the same. The initial response to the outbreak of a pandemic has always been denial. National and local governments have always been late to respond and have distorted facts and manipulated figures to deny the existence of the outbreak. In the early pages of “A Journal of the Plague Year,” the single most illuminating work of literature ever written on contagion and human behavior, Daniel Defoe reports that in 1664, local authorities in some neighborhoods of London tried to make the number of plague deaths appear lower than it was by registering other, invented diseases as the recorded cause of death.

ISTANBUL — For the past four years I have been writing a historical novel set in 1901 during what is known as the third plague pandemic, an outbreak of bubonic plague that killed millions of people in Asia but not very many in Europe. Over the last two months, friends and family, editors and journalists who know the subject of that novel, “Nights of Plague,” have been asking me a barrage of questions about pandemics. They are most curious about similarities between the current coronavirus pandemic and the historical outbreaks of plague and cholera. There is an overabundance of similarities. Throughout human and literary history what makes pandemics alike is not mere commonality of germs and viruses but that our initial responses were always the same. The initial response to the outbreak of a pandemic has always been denial. National and local governments have always been late to respond and have distorted facts and manipulated figures to deny the existence of the outbreak. In the early pages of “A Journal of the Plague Year,” the single most illuminating work of literature ever written on contagion and human behavior, Daniel Defoe reports that in 1664, local authorities in some neighborhoods of London tried to make the number of plague deaths appear lower than it was by registering other, invented diseases as the recorded cause of death. Over at Columbia University’s Weatherhead East Asian Institute:

Over at Columbia University’s Weatherhead East Asian Institute: