From Phys.Org:

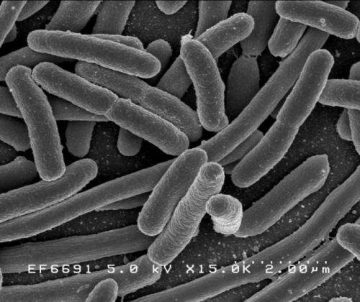

Bacteria have a cunning ability to survive in unfriendly environments. For example, through a complicated series of interactions, they can identify—and then build resistance to—toxic chemicals and metals, such as silver and copper. Bacteria rely on a similar mechanism for defending against antibiotics. In E. coli bacterium, the inner membrane sensor protein CusS mobilizes from a clustered form upon sensing copper ions in the environment. CusS recruits the transcription regulator protein CusR and then breaks down ATP to phosphorylate CusR, which then proceeds to activate gene expression to help the cell defend against the toxic copper ions. Cornell researchers combined genetic engineering, single-molecule tracking and protein quantitation to get a closer look at this mechanism and understand how it functions. The knowledge could lead to the development of more effective antibacterial treatments. The team’s paper, “Metal-Induced Sensor Mobilization Turns on Affinity to Activate Regulator for Metal Detoxification in Live Bacteria,” published May 28 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Bacteria have a cunning ability to survive in unfriendly environments. For example, through a complicated series of interactions, they can identify—and then build resistance to—toxic chemicals and metals, such as silver and copper. Bacteria rely on a similar mechanism for defending against antibiotics. In E. coli bacterium, the inner membrane sensor protein CusS mobilizes from a clustered form upon sensing copper ions in the environment. CusS recruits the transcription regulator protein CusR and then breaks down ATP to phosphorylate CusR, which then proceeds to activate gene expression to help the cell defend against the toxic copper ions. Cornell researchers combined genetic engineering, single-molecule tracking and protein quantitation to get a closer look at this mechanism and understand how it functions. The knowledge could lead to the development of more effective antibacterial treatments. The team’s paper, “Metal-Induced Sensor Mobilization Turns on Affinity to Activate Regulator for Metal Detoxification in Live Bacteria,” published May 28 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We were really interested in the fundamental mechanism,” said Peng Chen, the Peter J.W. Debye Professor of Chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences and the paper’s senior author. “The broader concept is that once we know the mechanism, then perhaps we can come up with better or alternative ways to compromise bacteria’s ability in defending against toxic chemicals. That will hopefully contribute to designing new ways of taming bacterial drug resistance.” The bacteria’s resistance is actually a tag-team operation, with two proteins working together inside the cell.

More here.