Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World:

Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World:

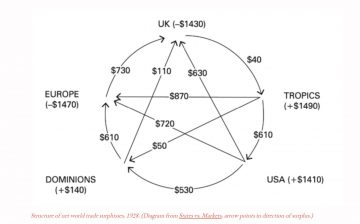

What does the US dollar’s continued dominance in the global monetary and financial systems mean for geo-economic and geo-political power? In a recent article, Yakov Feygin and Dominik Leusder question whether the United States actually enjoys an “exorbitant privilege” from the global use of the USD as the default currency for foreign exchange reserves, trade invoicing, and cross-border lending. Like Michael Pettis, they argue that the dollar’s primacy actually imposes an exorbitant burden through its differential costs on the US population.

Global use of the dollar largely benefits the top 1 percent of wealth holders in the United States, while imposing job losses and weak wage growth on much of the rest of the country. This situation flows from the structural requirements involved in having a given currency work as international money. As Randall Germain and I have argued in various venues, a country issuing a globally dominant currency necessarily runs a current account deficit.1 Prolonged current account deficits erode the domestic manufacturing base. And as current account deficits are funded by issuing various kinds of liabilities to the outside world, they necessarily involve a build-up of debt and other claims on US firms and households.

A large share of those foreign claims are on US firms in the form of corporate equity. US holdings of foreign firms’ equity are roughly equal in size, but these are largely held by the top 1 percent. The bulk of US debt to the rest of the world is public and private debt, including securitized mortgages. As the top 1 percent largely avoid taxation, the broad US public is on the hook for those debts. The rich reap the rewards of dollar dominance in the form of financial rents and easier tax avoidance. Meanwhile, the rest of us compete against artificially cheap low wage imports while struggling to find affordable housing.

More here.

John Altmann and Bryan W. Van Norden in the NYT:

John Altmann and Bryan W. Van Norden in the NYT: Faisal Devji reviews Judith Butler’s The Force of Nonviolence, in the LA Review of Books:

Faisal Devji reviews Judith Butler’s The Force of Nonviolence, in the LA Review of Books: John Robert Lewis was born in 1940 near the Black Belt town of Troy, Alabama. His parents were sharecroppers, and he grew up spending Sundays with a great-grandfather who was born into slavery, and hearing about the lynchings of Black men and women that were still a commonplace in the region. When Lewis was a few months old, the manager of a chicken farm named Jesse Thornton was lynched about twenty miles down the road, in the town of Luverne. His offense was referring to a police officer by his first name, not as “Mister.” A mob pursued Thornton, stoned and shot him, then dumped his body in a swamp; it was found, a week later, surrounded by vultures.

John Robert Lewis was born in 1940 near the Black Belt town of Troy, Alabama. His parents were sharecroppers, and he grew up spending Sundays with a great-grandfather who was born into slavery, and hearing about the lynchings of Black men and women that were still a commonplace in the region. When Lewis was a few months old, the manager of a chicken farm named Jesse Thornton was lynched about twenty miles down the road, in the town of Luverne. His offense was referring to a police officer by his first name, not as “Mister.” A mob pursued Thornton, stoned and shot him, then dumped his body in a swamp; it was found, a week later, surrounded by vultures. “Hamnet” is an exploration of marriage and grief written into the silent opacities of a life that is at once extremely famous and profoundly obscure. Countless scholars have combed through Elizabethan England’s parish and court records looking for traces of William Shakespeare. But what we know for sure, if set down unvarnished by learned and often fascinating speculation, would barely make a slender monograph. As William Styron once wrote, the historical novelist works best when fed on short rations. The rations at Maggie O’Farrell’s disposal are scant but tasty, just the kind of morsels to nourish an empathetic imagination. We know, for instance, that at the age of 18, Shakespeare married a woman named Anne or Agnes Hathaway, who was 26 and three months pregnant. (That condition wasn’t unusual for the time: Studies of marriage and baptism records reveal that as many as one-third of brides went to the altar pregnant.) Hathaway was the orphaned daughter of a farmer near Stratford-upon-Avon who had bequeathed her a dowry. This status gave her more latitude than many women of her time, who relied on paternal permission in choosing a mate.

“Hamnet” is an exploration of marriage and grief written into the silent opacities of a life that is at once extremely famous and profoundly obscure. Countless scholars have combed through Elizabethan England’s parish and court records looking for traces of William Shakespeare. But what we know for sure, if set down unvarnished by learned and often fascinating speculation, would barely make a slender monograph. As William Styron once wrote, the historical novelist works best when fed on short rations. The rations at Maggie O’Farrell’s disposal are scant but tasty, just the kind of morsels to nourish an empathetic imagination. We know, for instance, that at the age of 18, Shakespeare married a woman named Anne or Agnes Hathaway, who was 26 and three months pregnant. (That condition wasn’t unusual for the time: Studies of marriage and baptism records reveal that as many as one-third of brides went to the altar pregnant.) Hathaway was the orphaned daughter of a farmer near Stratford-upon-Avon who had bequeathed her a dowry. This status gave her more latitude than many women of her time, who relied on paternal permission in choosing a mate. One night in August 2005, just after I’d moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for a job as a theology professor, I needed beer. To get to the distributor, I drove over a concrete bridge, its four pylons etched with words like “Perseverance” and “Industry” and topped by monumental eagles. Once there, I wandered through the pallets of warm cases trying to find a thirty-pack of PBR until the thin, gruff man behind the counter asked what I was looking for. I told him, he pointed to the right pallet, and I met him at the register.

One night in August 2005, just after I’d moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for a job as a theology professor, I needed beer. To get to the distributor, I drove over a concrete bridge, its four pylons etched with words like “Perseverance” and “Industry” and topped by monumental eagles. Once there, I wandered through the pallets of warm cases trying to find a thirty-pack of PBR until the thin, gruff man behind the counter asked what I was looking for. I told him, he pointed to the right pallet, and I met him at the register. Seven years ago

Seven years ago The thesis of Bjorn Lomborg’s “False Alarm” is simple and simplistic: Activists have been sounding a false alarm about the dangers of climate change. If we listen to them, Lomborg says, we will waste trillions of dollars, achieve little and the poor will suffer the most. Science has provided a way to carefully balance costs and benefits, if we would only listen to its clarion call. And, of course, the villain in this “false alarm,” the boogeyman for all of society’s ills, is the hyperventilating media. Lomborg doesn’t use the term “fake news,” but it’s there if you read between the lines.

The thesis of Bjorn Lomborg’s “False Alarm” is simple and simplistic: Activists have been sounding a false alarm about the dangers of climate change. If we listen to them, Lomborg says, we will waste trillions of dollars, achieve little and the poor will suffer the most. Science has provided a way to carefully balance costs and benefits, if we would only listen to its clarion call. And, of course, the villain in this “false alarm,” the boogeyman for all of society’s ills, is the hyperventilating media. Lomborg doesn’t use the term “fake news,” but it’s there if you read between the lines. T

T This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like.

This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like. In the summer of 1977, on a field trip in northern Patagonia, the American archaeologist Tom Dillehay made a stunning discovery. Digging by a creek in a nondescript scrubland called Monte Verde, in southern Chile, he came upon the remains of an ancient camp. A full excavation uncovered the trace wooden foundations of no fewer than 12 huts, plus one larger structure designed for tool manufacture and perhaps as an infirmary. In the large hut, Dillehay found gnawed bones, spear points, grinding tools and, hauntingly, a human footprint in the sand. The ancestral Patagonians—inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego and the Magellan Straits—had erected their domestic quarters using branches from the beech trees of a long-gone temperate forest, then covered them with the hides of vanished ice age species, including mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths.

In the summer of 1977, on a field trip in northern Patagonia, the American archaeologist Tom Dillehay made a stunning discovery. Digging by a creek in a nondescript scrubland called Monte Verde, in southern Chile, he came upon the remains of an ancient camp. A full excavation uncovered the trace wooden foundations of no fewer than 12 huts, plus one larger structure designed for tool manufacture and perhaps as an infirmary. In the large hut, Dillehay found gnawed bones, spear points, grinding tools and, hauntingly, a human footprint in the sand. The ancestral Patagonians—inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego and the Magellan Straits—had erected their domestic quarters using branches from the beech trees of a long-gone temperate forest, then covered them with the hides of vanished ice age species, including mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths. A breathalyzer designed to detect multiple cancers early is being tested in the UK. Several illnesses

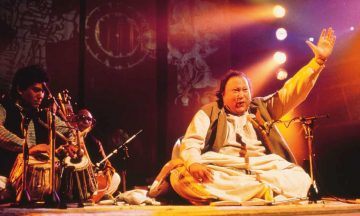

A breathalyzer designed to detect multiple cancers early is being tested in the UK. Several illnesses Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan In 1931, the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel pulled off arguably one of the most stunning intellectual achievements in history.

In 1931, the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel pulled off arguably one of the most stunning intellectual achievements in history. There are two boxes on a table, one red and one green. One contains a treasure. The red box is labelled “exactly one of the labels is true”. The green box is labelled “the treasure is in this box.”

There are two boxes on a table, one red and one green. One contains a treasure. The red box is labelled “exactly one of the labels is true”. The green box is labelled “the treasure is in this box.”