Ode to a Can of Schaefer Beer

…. We would like to

…. express our sincere

…. thanks to our

…. Schaefer customers

…. for their loyalty

…. and support

It is brewed in Milwaukee Wisconsin.

It knows its place.

It wears its heart on its sleeve

like a poem,

laid out like a poem

with weak line endings and questionable

closure. Its idiom

would not be unfamiliar

to a Soviet film director,

its emblem a stylized stalk

of bronzed wheat,

circlets of flowering hops

as sketched by a WPA draftsman

for a post office mural in 1934.

It conjures a forgotten social contract

between consumers and producers,

a world of feudal fealty—

the corporation

is your friend, your loyalty

shall be rewarded—a vision

of benign paternalism

last seen in Father Knows Best

and agitprop depictions of Mao

sharing party wisdom with eager villagers,

bestowing avuncular unction.

It was, once, the one

beer to have

when you’re having more than one,

slogan and message

outdated as giant ground sloths roaming

the forests of Nebraska,

irrecoverable

as the ex-cheerleader

watching her toddler eating handfuls of sand

at the playground

considers that lost world of pom poms

and rah-rah-let’s-go-team

to be.

During the past few years of Donald Trump’s deranged presidency, if there is one writer I turn to it is Masha Gessen, whose piercing clarity is gemlike and refusal to equivocate precious. Their ability – Gessen is non–binary/trans and uses they/them pronouns – is surely to do with their Russian American background. As a journalist, Gessen has covered Russia, Hungary and Israel, so is not experiencing illiberalism for the first time. Instead of a weariness however, what is present in the book is a stunning capacity to connect the dots in a way that few can.

During the past few years of Donald Trump’s deranged presidency, if there is one writer I turn to it is Masha Gessen, whose piercing clarity is gemlike and refusal to equivocate precious. Their ability – Gessen is non–binary/trans and uses they/them pronouns – is surely to do with their Russian American background. As a journalist, Gessen has covered Russia, Hungary and Israel, so is not experiencing illiberalism for the first time. Instead of a weariness however, what is present in the book is a stunning capacity to connect the dots in a way that few can.  Wearable technologies offer a convenient means of monitoring many physiological features, presenting a multitude of medical solutions. Not only are these devices easy for the consumer to use, but they offer real-time data for physicians to analyze as well. From the

Wearable technologies offer a convenient means of monitoring many physiological features, presenting a multitude of medical solutions. Not only are these devices easy for the consumer to use, but they offer real-time data for physicians to analyze as well. From the  “Never look a hog in the eyes,” an experienced hand told anthropologist Alex Blanchette as they prepared to artificially inseminate sows. “If the animals think you are looking at them, they will freeze.” Like a living, inverted panopticon, hundreds of pigs would watch their handlers from their pens with a petrifying gaze. “They have almost 360 degrees vision,” a former worker recollected. “Sometimes they look like they are not looking at you. . . . but if you look at their eyes, you will see that they are always following you.”

“Never look a hog in the eyes,” an experienced hand told anthropologist Alex Blanchette as they prepared to artificially inseminate sows. “If the animals think you are looking at them, they will freeze.” Like a living, inverted panopticon, hundreds of pigs would watch their handlers from their pens with a petrifying gaze. “They have almost 360 degrees vision,” a former worker recollected. “Sometimes they look like they are not looking at you. . . . but if you look at their eyes, you will see that they are always following you.” Despite occasional and important disagreements, most people are in rough agreement about what it means to be moral, to do the right thing. There’s much less agreement about why we should be moral, or even what kind of answer to that question could be convincing. Philosopher Russ Shafer-Landau is one of the leading proponents of

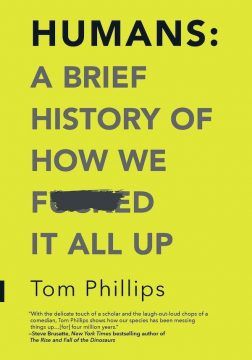

Despite occasional and important disagreements, most people are in rough agreement about what it means to be moral, to do the right thing. There’s much less agreement about why we should be moral, or even what kind of answer to that question could be convincing. Philosopher Russ Shafer-Landau is one of the leading proponents of  THE WORLD IS LITTERED with the consequences of monumental human screw-ups — environmental, economic, political, social, and now, as we deal with a pandemic, health-related. You might even claim, as Tom Phillips does in Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up, that these screw-ups are a defining characteristic of humankind. There’s the everyday type that you and I commit — say, accidentally shattering your phone’s screen on the sidewalk — and then there’s the scaled-up kind — say, killing a river or triggering a famine that results in millions of deaths. In his book, Phillips walks us through tens of thousands of years of human-caused disasters, the results of systematic mistakes that people seem unwilling or unable to learn from.

THE WORLD IS LITTERED with the consequences of monumental human screw-ups — environmental, economic, political, social, and now, as we deal with a pandemic, health-related. You might even claim, as Tom Phillips does in Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up, that these screw-ups are a defining characteristic of humankind. There’s the everyday type that you and I commit — say, accidentally shattering your phone’s screen on the sidewalk — and then there’s the scaled-up kind — say, killing a river or triggering a famine that results in millions of deaths. In his book, Phillips walks us through tens of thousands of years of human-caused disasters, the results of systematic mistakes that people seem unwilling or unable to learn from. In 1968 an exhibit entitled Cybernetic Serendipity: The Computer and the Arts was held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. The first major event of its kind, Cybernetic Serendipity’s aim was to “

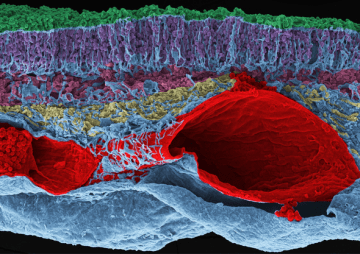

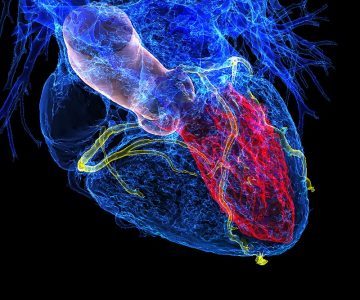

In 1968 an exhibit entitled Cybernetic Serendipity: The Computer and the Arts was held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. The first major event of its kind, Cybernetic Serendipity’s aim was to “ Current methods for predicting heart attacks are woefully outdated, says Cheerag Shirodaria, a cardiologist at the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK. “We basically look at a patient’s age, obesity and whether they have diabetes. The most sophisticated we get is measuring their cholesterol,” he says. Heart attacks are often caused when fatty accumulations inside arteries, known as plaques, result in the narrowing of blood vessels. These plaques then rupture and form blood clots. Age, being overweight or obese and having diabetes are all risk factors, and people in at-risk groups are closely monitored. “But 50% of heart attacks are in people without narrowing, and they’re being missed by current tests,” he says. A desire to drag prognosis into the modern era is what pushed Shirodaria and a group of like-minded cardiologists to set up Caristo Diagnostics. Rather than blood-vessel narrowing, the team focuses on another driver of plaque ruptures — vascular inflammation. The company uses algorithms to analyse information that until now has been hidden in the noise of computed tomography (CT) scans. This enables it to assess inflammation and calculate the likelihood that a person will have a heart attack in a given time period.

Current methods for predicting heart attacks are woefully outdated, says Cheerag Shirodaria, a cardiologist at the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK. “We basically look at a patient’s age, obesity and whether they have diabetes. The most sophisticated we get is measuring their cholesterol,” he says. Heart attacks are often caused when fatty accumulations inside arteries, known as plaques, result in the narrowing of blood vessels. These plaques then rupture and form blood clots. Age, being overweight or obese and having diabetes are all risk factors, and people in at-risk groups are closely monitored. “But 50% of heart attacks are in people without narrowing, and they’re being missed by current tests,” he says. A desire to drag prognosis into the modern era is what pushed Shirodaria and a group of like-minded cardiologists to set up Caristo Diagnostics. Rather than blood-vessel narrowing, the team focuses on another driver of plaque ruptures — vascular inflammation. The company uses algorithms to analyse information that until now has been hidden in the noise of computed tomography (CT) scans. This enables it to assess inflammation and calculate the likelihood that a person will have a heart attack in a given time period. A certain mythology has gathered around the thirty-five year hiatus that followed Coursil’s incredibly fruitful period of musical cosmopolitanism. There is a romantic obscurity to the way in which jazz fans discuss the career interruptions of their favorite players, mistaking hard times and financial exigencies for semi-monastic trials of spirit. A prime example would be Sonny Rollins, who retreated into a prolonged rehearsal session at the height of his fame, practicing all hours on the Williamsburg bridge and bearing solitary witness to the city; or Dexter Gordon, whose incarceration in the fifties secured his reputation as the perennial ambassador of bebop, and an intercontinental comeback kid. Other disappearances are far more lacunar and prolonged, such as that of sought-after bassist Henry Grimes, who devoted himself to poetry and literature during a decades-long stint in the workaday world, only to emerge with startling vigor in the early twenty-first century.

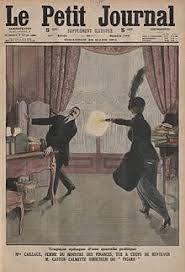

A certain mythology has gathered around the thirty-five year hiatus that followed Coursil’s incredibly fruitful period of musical cosmopolitanism. There is a romantic obscurity to the way in which jazz fans discuss the career interruptions of their favorite players, mistaking hard times and financial exigencies for semi-monastic trials of spirit. A prime example would be Sonny Rollins, who retreated into a prolonged rehearsal session at the height of his fame, practicing all hours on the Williamsburg bridge and bearing solitary witness to the city; or Dexter Gordon, whose incarceration in the fifties secured his reputation as the perennial ambassador of bebop, and an intercontinental comeback kid. Other disappearances are far more lacunar and prolonged, such as that of sought-after bassist Henry Grimes, who devoted himself to poetry and literature during a decades-long stint in the workaday world, only to emerge with startling vigor in the early twenty-first century. Of the millions of bullets fired in 1914, only two changed history: the bullet fired on June 28 in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip’s Browning automatic that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and the bullet fired on March 16 in Paris by Henriette Caillaux that killed Gaston Calmette. As premier in 1911, her husband had by back-channel negotiations defused a war-charged crisis with Germany, grounds for believing he could have worked his magic again three years later, when he would have all but certainly been elected premier again—but for the bark of Henriette’s Browning. Months before the war, anticipating that Caillaux, then the finance minister, would soon be premier, Belgium’s ambassador to Paris assured Brussels: “Caillaux’s presence in power will lessen the acuteness of international jealousies and will constitute a better base for relations between France and Germany.” That was heresy in “official Paris,” where “everybody that you meet tells you that an early war with Germany is certain and inevitable.” Months into the war, the Kölnische Zeitung stated, “If Monsieur Caillaux had remained in office, if Madame Caillaux’s gesture had not been made, the plot against the peace of Europe would not have succeeded.”

Of the millions of bullets fired in 1914, only two changed history: the bullet fired on June 28 in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip’s Browning automatic that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and the bullet fired on March 16 in Paris by Henriette Caillaux that killed Gaston Calmette. As premier in 1911, her husband had by back-channel negotiations defused a war-charged crisis with Germany, grounds for believing he could have worked his magic again three years later, when he would have all but certainly been elected premier again—but for the bark of Henriette’s Browning. Months before the war, anticipating that Caillaux, then the finance minister, would soon be premier, Belgium’s ambassador to Paris assured Brussels: “Caillaux’s presence in power will lessen the acuteness of international jealousies and will constitute a better base for relations between France and Germany.” That was heresy in “official Paris,” where “everybody that you meet tells you that an early war with Germany is certain and inevitable.” Months into the war, the Kölnische Zeitung stated, “If Monsieur Caillaux had remained in office, if Madame Caillaux’s gesture had not been made, the plot against the peace of Europe would not have succeeded.” To include the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita in a series called “Footnotes to Plato” may seem odd for many reasons – some obvious, some less so. But to address the oddity is invigorating, and offers a way of considering the necessity of placing these works in the wider discussion, as well as the historical and conceptual impediments to doing so.

To include the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita in a series called “Footnotes to Plato” may seem odd for many reasons – some obvious, some less so. But to address the oddity is invigorating, and offers a way of considering the necessity of placing these works in the wider discussion, as well as the historical and conceptual impediments to doing so. It has been just over five months since the first case of COVID-19 was detected in India. With nearly a million confirmed cases, the country now has the third greatest number of infections, behind only the United States and Brazil. At least 25,000 people have died.

It has been just over five months since the first case of COVID-19 was detected in India. With nearly a million confirmed cases, the country now has the third greatest number of infections, behind only the United States and Brazil. At least 25,000 people have died.