Basharat Peer in The New York Times:

DEVARI, India — Somebody took a photograph on the side of a highway in India. On a clearing of baked earth, a lithe, athletic man holds his friend in his lap. A red bag and a half empty bottle of water are at his side. The first man is leaning over his friend like a canopy, his face is anxious and his eyes searching his friend’s face for signs of life. The man is small and wiry, in a light green T-shirt and a faded pair of jeans. He is sick, and seems barely conscious. His hair is soaked and sticking to his scalp, a sparse stubble lines the deathlike pallor of his face, his eyes are closed, and his darkened lips are half parted. The lid of the water bottle is open. His friend’s cupped hand is about to pour some water on his feverish, dehydrated lips.

DEVARI, India — Somebody took a photograph on the side of a highway in India. On a clearing of baked earth, a lithe, athletic man holds his friend in his lap. A red bag and a half empty bottle of water are at his side. The first man is leaning over his friend like a canopy, his face is anxious and his eyes searching his friend’s face for signs of life. The man is small and wiry, in a light green T-shirt and a faded pair of jeans. He is sick, and seems barely conscious. His hair is soaked and sticking to his scalp, a sparse stubble lines the deathlike pallor of his face, his eyes are closed, and his darkened lips are half parted. The lid of the water bottle is open. His friend’s cupped hand is about to pour some water on his feverish, dehydrated lips.

I saw this photo in May, as it was traveling across Indian social media. News stories filled in some of the details: It was taken on May 15 on the outskirts of Kolaras, a small town in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. The two young men were childhood friends: Mohammad Saiyub, a 22-year-old Muslim, and Amrit Kumar, a 24-year-old Dalit, which refers to former “untouchables,” who have suffered the greatest violence and discrimination under the centuries-old Hindu caste system. Over the next few weeks, I found myself returning to that moment preserved and isolated by the photograph. I came across some details about their lives in the Indian press: The boys came from a small village called Devari in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. They had been working in Surat, a city on the west coast, and were making their way home, part of a mass migration that began when the Indian government ordered a national lockdown to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. Despite our image-saturated times, the photograph began assuming greater meanings for me.

For the past six years, since Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party took power, it has seemed as if a veil covering India’s basest impulses has been removed. The ideas of civility, grace and tolerance were replaced by triumphalist displays of prejudice, sexism, hate speech and abuse directed at women, minorities and liberals. This culture of vilification dominates India’s television networks, social media and the immensely popular mobile messaging service WhatsApp. When you do come across acts of kindness and compassion, they seem to be documented and calibrated to serve the gods of exhibitionism and self-promotion. The photograph of Amrit and Saiyub came like a gentle rain from heaven on India’s hate-filled public sphere. The gift of friendship and trust it captured filled me with a certain sadness, as it felt so rare. I felt compelled to find out more about their lives and journeys.

More here.

Our blood and cells are complex mixtures of DNA, RNA, proteins, metabolites, lipids, sugars, metal ions, and more. All of these are deeply important in informing our health and wellness. Today, we can measure a few of these molecules routinely, but what are we missing might be in the rest of the data. Dalton Bioanalytics is creating a comprehensive and inexpensive method to look at all these molecules to bring about truly multiomics data. I sat with Austin Quach, CSO of Dalton Bioanalytics, to talk about his platform from inventing it in his lab to starting a company.

Our blood and cells are complex mixtures of DNA, RNA, proteins, metabolites, lipids, sugars, metal ions, and more. All of these are deeply important in informing our health and wellness. Today, we can measure a few of these molecules routinely, but what are we missing might be in the rest of the data. Dalton Bioanalytics is creating a comprehensive and inexpensive method to look at all these molecules to bring about truly multiomics data. I sat with Austin Quach, CSO of Dalton Bioanalytics, to talk about his platform from inventing it in his lab to starting a company. According to medieval Jewish commentaries on the Torah, heaven will be dazzling and dramatic. It will contain chambers “built of silver and gold, ornamented with pearls.” New arrivals will pass through gates guarded by 600,000 angels and bathed in “248 rivulets of balsam and attar.” The righteous will attend elaborate feasts and lounge in lavish gardens. As a rule, paintings of heaven are more vague and more amorphous than paintings of hell, but avuncular artists still stuff them with cherry-cheeked cherubs. In the New Testament, John promises his followers that God’s “house has many rooms.”

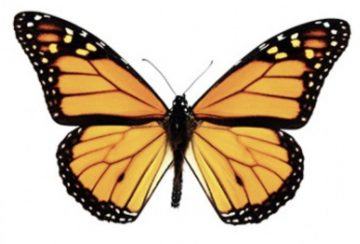

According to medieval Jewish commentaries on the Torah, heaven will be dazzling and dramatic. It will contain chambers “built of silver and gold, ornamented with pearls.” New arrivals will pass through gates guarded by 600,000 angels and bathed in “248 rivulets of balsam and attar.” The righteous will attend elaborate feasts and lounge in lavish gardens. As a rule, paintings of heaven are more vague and more amorphous than paintings of hell, but avuncular artists still stuff them with cherry-cheeked cherubs. In the New Testament, John promises his followers that God’s “house has many rooms.” In coming weeks, the Northeast of the United States will experience the peak of its annual migration of monarch butterflies. The butterflies’ life cycle takes place over an astonishingly broad geographic range. Each year, the monarchs overwinter by the millions in the high-altitude forests of Mexico. Then, in the spring and summer, they head north to the United States and southern Canada, the northern limit of where milkweed, the only plants that the fastidious monarchs breed on, will grow.

In coming weeks, the Northeast of the United States will experience the peak of its annual migration of monarch butterflies. The butterflies’ life cycle takes place over an astonishingly broad geographic range. Each year, the monarchs overwinter by the millions in the high-altitude forests of Mexico. Then, in the spring and summer, they head north to the United States and southern Canada, the northern limit of where milkweed, the only plants that the fastidious monarchs breed on, will grow. A philosopher and cultural critic, Santiago Zabala is well known for articulating the ongoing relevance of a strand of philosophy oriented around interpretation: philosophical hermeneutics. In his latest book, he brings his hermeneutic perspective to an interrogation of the mounting challenges posed by the conditions of today’s intellectual and political landscape. As the subtitle indicates, this book addresses the misinformation and misunderstandings that are so prevalent today. Alternative facts, fake news and post-truth are all symptoms of a lack of any mutual understanding about what is real. Similarly, the return of realism has become a trend in the intellectual world, reflected in the realist rationality proffered by a psychologist like Jordan Peterson or by the philosophical movement of speculative realism. Questions about what is real have never been so pressing on a global scale. Indeed, responses to those questions have impacts not only on humanity but on the diversity of species on Earth, which are currently threatened with a mass extinction event.

A philosopher and cultural critic, Santiago Zabala is well known for articulating the ongoing relevance of a strand of philosophy oriented around interpretation: philosophical hermeneutics. In his latest book, he brings his hermeneutic perspective to an interrogation of the mounting challenges posed by the conditions of today’s intellectual and political landscape. As the subtitle indicates, this book addresses the misinformation and misunderstandings that are so prevalent today. Alternative facts, fake news and post-truth are all symptoms of a lack of any mutual understanding about what is real. Similarly, the return of realism has become a trend in the intellectual world, reflected in the realist rationality proffered by a psychologist like Jordan Peterson or by the philosophical movement of speculative realism. Questions about what is real have never been so pressing on a global scale. Indeed, responses to those questions have impacts not only on humanity but on the diversity of species on Earth, which are currently threatened with a mass extinction event. Imagine reading a story titled “The Relentless Pursuit of Booze.” You would likely expect a depressing story about a person in a downward alcoholic spiral. Now imagine instead reading a story titled “The Relentless Pursuit of Success.” That would be an inspiring story, wouldn’t it? Maybe—but maybe not. It might well be the story of someone whose never-ending quest for more and more success leaves them perpetually unsatisfied and incapable of happiness. Physical dependency keeps alcoholics committed to their vice, even as it wrecks their happiness. But arguably more powerful than the physical addiction is the sense that drinking is a relationship, not an activity. As the author Caroline Knapp described alcoholism in her memoir

Imagine reading a story titled “The Relentless Pursuit of Booze.” You would likely expect a depressing story about a person in a downward alcoholic spiral. Now imagine instead reading a story titled “The Relentless Pursuit of Success.” That would be an inspiring story, wouldn’t it? Maybe—but maybe not. It might well be the story of someone whose never-ending quest for more and more success leaves them perpetually unsatisfied and incapable of happiness. Physical dependency keeps alcoholics committed to their vice, even as it wrecks their happiness. But arguably more powerful than the physical addiction is the sense that drinking is a relationship, not an activity. As the author Caroline Knapp described alcoholism in her memoir  D

D For that matter, Kant’s rigorous discipline turns out to be contagious. Though he was unmarried, he didn’t live alone—he had a household and spent much time interacting with his friend and unofficial majordomo Wasianski (played by André Wilms) and the manservant Lampe (Roland Amstutz)—and much of the movie’s action is centered on Kant’s obsessional domestic routine and the petty agonies of its perturbations. (The script, by Collin and André Scala, is loosely based on the memoirs of the real-life Wasianski,

For that matter, Kant’s rigorous discipline turns out to be contagious. Though he was unmarried, he didn’t live alone—he had a household and spent much time interacting with his friend and unofficial majordomo Wasianski (played by André Wilms) and the manservant Lampe (Roland Amstutz)—and much of the movie’s action is centered on Kant’s obsessional domestic routine and the petty agonies of its perturbations. (The script, by Collin and André Scala, is loosely based on the memoirs of the real-life Wasianski,

Chris Dillow writes perhaps the most interesting

Chris Dillow writes perhaps the most interesting  The world’s largest nuclear fusion project began its five-year assembly phase on Tuesday in southern

The world’s largest nuclear fusion project began its five-year assembly phase on Tuesday in southern  We live in a time of personal timorousness and collective mercilessness.

We live in a time of personal timorousness and collective mercilessness. For the poet Seamus Heaney—a kind of laureate of the bog—the landscape always had a “strange assuaging effect . . . with associations reaching back into early childhood.” The bog was liberty and community, as well as labor. This ambiguous, borderless terrain—neither living nor dead, wet nor dry, public nor private—has never been politically neutral. Ireland’s bogs were often viewed by city dwellers as fundamentally moribund: economic and cultural voids, the refuge of brigands, outcasts, and hermits, synonymous with a semi-bestial peasantry—“miserable and half-starved specters,” according to one nineteenth-century account. In folklore, bogs are the lairs of the shape-shifting púca—an 1828 study of fairy mythology called them “wicked-minded, black-looking, bad things”—while in Edna O’Brien’s classic 1960 novel The Country Girls, the protagonists are contemptuously dismissed as “fresh from the bogs.”

For the poet Seamus Heaney—a kind of laureate of the bog—the landscape always had a “strange assuaging effect . . . with associations reaching back into early childhood.” The bog was liberty and community, as well as labor. This ambiguous, borderless terrain—neither living nor dead, wet nor dry, public nor private—has never been politically neutral. Ireland’s bogs were often viewed by city dwellers as fundamentally moribund: economic and cultural voids, the refuge of brigands, outcasts, and hermits, synonymous with a semi-bestial peasantry—“miserable and half-starved specters,” according to one nineteenth-century account. In folklore, bogs are the lairs of the shape-shifting púca—an 1828 study of fairy mythology called them “wicked-minded, black-looking, bad things”—while in Edna O’Brien’s classic 1960 novel The Country Girls, the protagonists are contemptuously dismissed as “fresh from the bogs.” The idea of negation was central to the tensions Hesse created and mediated in her sculptures. One of her favourite descriptions of them was ‘chaos structured as non-chaos’: it captures the distinctive look of her work and its commitment to disruptive repetition. Her graph paper drawings put the contradiction to work, the essential orderliness of a grid providing her with a structure for her chaos. When she chose a green-ruled variety as the matrix for a tightly inked pattern, it was so that the opposition between line and circle, the harmony of repeated shapes and the freeform, would seem almost to hum on the page. This piece is one among hundreds of drawings included in Eva Hesse Oberlin, a travelling exhibition distilled from the enormous collection of Hesse’s works and papers (some 1500 items) housed at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College in Ohio. Hesse wasn’t educated at Oberlin, but at Yale: it was her elder sister, Helen, who chose Oberlin for reasons that, many years later, seem both savvy and poignant.

The idea of negation was central to the tensions Hesse created and mediated in her sculptures. One of her favourite descriptions of them was ‘chaos structured as non-chaos’: it captures the distinctive look of her work and its commitment to disruptive repetition. Her graph paper drawings put the contradiction to work, the essential orderliness of a grid providing her with a structure for her chaos. When she chose a green-ruled variety as the matrix for a tightly inked pattern, it was so that the opposition between line and circle, the harmony of repeated shapes and the freeform, would seem almost to hum on the page. This piece is one among hundreds of drawings included in Eva Hesse Oberlin, a travelling exhibition distilled from the enormous collection of Hesse’s works and papers (some 1500 items) housed at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College in Ohio. Hesse wasn’t educated at Oberlin, but at Yale: it was her elder sister, Helen, who chose Oberlin for reasons that, many years later, seem both savvy and poignant.