Scott Anderson in The New York Times:

Although Mark Twain apparently didn’t coin the phrase “truth is stranger than fiction,” he offered perhaps the best explanation for why it is so. “It is because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities,” he wrote. “Truth isn’t.” History is replete with proof; try, for instance, plotting a novel that faithfully replicates the events of Sept. 11 or John F. Kennedy’s assassination and watch it be dismissed as absurd.

Although Mark Twain apparently didn’t coin the phrase “truth is stranger than fiction,” he offered perhaps the best explanation for why it is so. “It is because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities,” he wrote. “Truth isn’t.” History is replete with proof; try, for instance, plotting a novel that faithfully replicates the events of Sept. 11 or John F. Kennedy’s assassination and watch it be dismissed as absurd.

This phenomenon takes on special resonance when the vagaries of circumstance are compounded by human idiocy, as is the case with the catalyzing event in Jennet Conant’s “The Great Secret.”

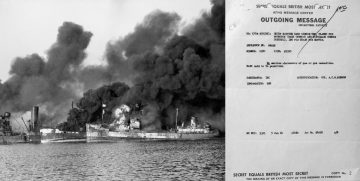

Here’s the setup: Skirting an international ban on the use of chemical weapons, an American merchant ship carrying a top-secret shipment of nitrogen mustard gas shells slips into the port city of Bari mere months after Italy’s surrender to the Allied forces. Despite the ship’s highly explosive cargo, its captain is told to berth in the overcrowded harbor and await his turn in the unloading queue, a wait that extends for five days. And despite Bari being a mere 150 miles from the German front lines, the Allies are so convinced of their air supremacy that they don’t even bother putting up a fighter screen to guard the port; to the contrary, to facilitate round-the-clock unloading operations, authorities have dispensed with the usual blackout rules, so that on the night of Dec. 2, 1943, the place is lit up like a Christmas tree. Oh, and the one telephone linked to air command that might alert fighters that a great squadron of German bombers is bearing down on the harbor? Yeah, for some reason the phone isn’t working that night. In the hands of an accomplished writer like Conant, whose earlier works include the best sellers “Tuxedo Park” and “The Irregulars,” this real-life scenario — and resulting disaster — offers great, if awful, promise.

More here.