Family Trees

—for the 2016 Guam Soil and Water Conservation Districts’ Educator Symposium

1

Before we enter the jungle, my dad

asks permission of the spirits who dwell

within. He walks slowly, with care,

to teach me, like his father taught him,

how to show respect. Then he stops

and closes his eyes to teach me

how to listen. Ekungok, as the winds

exhale and billow the canopy, tremble

the understory, and conduct the wild

orchestra of all breathing things.

2

“Niyok, Lemmai, Ifit, Yoga’, Nunu,” he chants

in a tone of reverence, calling forth the names

of each tree, each elder, who has provided us

with food and medicine, clothes and tools,

canoes and shelter. Like us, they grew in dark

wombs, sprouted from seeds, were nourished

by the light. Like us, they survived the storms

of conquest. Like us, roots anchor them to this

island, giving breath, giving strength to reach

towards the Pacific sky and blossom.

3

“When you take,” my dad says, “Take with

gratitude, and never more than what you need.”

He teaches me the phrase, “eminent domain,”

which means “theft,” means “to turn a place

of abundance into a base of destruction.”

The military uprooted trees with bulldozers,

paved the fertile earth with concrete, and planted

toxic chemicals and ordnances in the ground.

Barbed wire fences spread like invasive vines,

whose only fruit are the cancerous tumors

that bloom on every branch of our family tree.

Biologists like to think of themselves as properly scientific behaviourists, explaining and predicting the ways that proteins, organelles, cells, plants, animals and whole biota behave under various conditions, thanks to the smaller parts of which they are composed. They identify causal mechanisms that reliably execute various functions such as copying DNA, attacking antigens, photosynthesising, discerning temperature gradients, capturing prey, finding their way back to their nests and so forth, but they don’t think that this acknowledgment of functions implicates them in any discredited teleology or imputation of reasons and purposes or understanding to the cells and other parts of the mechanisms they investigate.

Biologists like to think of themselves as properly scientific behaviourists, explaining and predicting the ways that proteins, organelles, cells, plants, animals and whole biota behave under various conditions, thanks to the smaller parts of which they are composed. They identify causal mechanisms that reliably execute various functions such as copying DNA, attacking antigens, photosynthesising, discerning temperature gradients, capturing prey, finding their way back to their nests and so forth, but they don’t think that this acknowledgment of functions implicates them in any discredited teleology or imputation of reasons and purposes or understanding to the cells and other parts of the mechanisms they investigate.

Shelby Steele is experiencing a revival. For over 30 years, the controversial black American essayist and culture critic has consistently produced some of the most original insights to be found on the precarious issue of race in America and has been met with reactions that range from reverence to revulsion. Usually, it’s one reaction or the other. To his critics, Steele is a race traitor, a contrarian black conservative who makes a living assuaging the guilty consciences of whites at the expense of his own people. To his admirers, he is a lone voice of clarity in the chaos of America’s racial discourse who, at 74 years of age, continues to speak uncomfortable and disconcerting truths to power. But his greatest strength may turn out to be a knack for anticipation. As the social upheavals inspired by America’s “racial reckoning” rage on, Steele’s work now looks prescient—it identified the underlying forces that would eventually shape our explosive cultural moment, and offers a more honest accounting of our past and present.

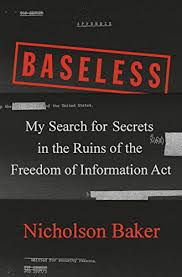

Shelby Steele is experiencing a revival. For over 30 years, the controversial black American essayist and culture critic has consistently produced some of the most original insights to be found on the precarious issue of race in America and has been met with reactions that range from reverence to revulsion. Usually, it’s one reaction or the other. To his critics, Steele is a race traitor, a contrarian black conservative who makes a living assuaging the guilty consciences of whites at the expense of his own people. To his admirers, he is a lone voice of clarity in the chaos of America’s racial discourse who, at 74 years of age, continues to speak uncomfortable and disconcerting truths to power. But his greatest strength may turn out to be a knack for anticipation. As the social upheavals inspired by America’s “racial reckoning” rage on, Steele’s work now looks prescient—it identified the underlying forces that would eventually shape our explosive cultural moment, and offers a more honest accounting of our past and present. Baker has long been intrigued by the fact that the declassified versions of government documents concerning bioweapons from this era that are available still tend to be heavily censored. The continued secrecy, for him, raises a striking question: What other information do these documents contain that remains so sensitive after all this time that the US government continues to hide it from the American public and the rest of the world under these redactions?

Baker has long been intrigued by the fact that the declassified versions of government documents concerning bioweapons from this era that are available still tend to be heavily censored. The continued secrecy, for him, raises a striking question: What other information do these documents contain that remains so sensitive after all this time that the US government continues to hide it from the American public and the rest of the world under these redactions? In late August, the singer, songwriter, and guitarist Adrianne Lenker stood beside a creek in upstate New York, watching the water move. The day before, Lenker, who is twenty-nine, had packed up the Brooklyn apartment she’d been sharing with two roommates. She was preparing to haul a vintage camping trailer across the country to Topanga Canyon, on the west side of Los Angeles, where her band,

In late August, the singer, songwriter, and guitarist Adrianne Lenker stood beside a creek in upstate New York, watching the water move. The day before, Lenker, who is twenty-nine, had packed up the Brooklyn apartment she’d been sharing with two roommates. She was preparing to haul a vintage camping trailer across the country to Topanga Canyon, on the west side of Los Angeles, where her band,  We “data people” have all been burnt by polling – and it hurts. In Britain, America and elsewhere, there have been enough high profile “misses” by the industry to give anyone cold feet about relying on polls as the sole metric for how an election might play out. On balance, however, polling has good form for calling most races right – and is becoming increasingly accurate. If this comes as a surprise, it might be because humans often process negative memories (poll misses) more thoroughly than they do positive (accurate polls). Perhaps conscious that history may repeat itself, betting markets are

We “data people” have all been burnt by polling – and it hurts. In Britain, America and elsewhere, there have been enough high profile “misses” by the industry to give anyone cold feet about relying on polls as the sole metric for how an election might play out. On balance, however, polling has good form for calling most races right – and is becoming increasingly accurate. If this comes as a surprise, it might be because humans often process negative memories (poll misses) more thoroughly than they do positive (accurate polls). Perhaps conscious that history may repeat itself, betting markets are  On January 1804, the West Indian island of Saint-Domingue became the world’s first black republic. The Africans toiling on the sugar-rich plantations overthrew their French masters and declared independence. The name Saint-Domingue was replaced by the aboriginal Taíno Indian word

On January 1804, the West Indian island of Saint-Domingue became the world’s first black republic. The Africans toiling on the sugar-rich plantations overthrew their French masters and declared independence. The name Saint-Domingue was replaced by the aboriginal Taíno Indian word

Astronomers rocked the cosmological world with the 1998 discovery that the universe is accelerating. Well-deserved Nobel Prizes were awarded to Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, and today’s guest Adam Riess. Adam has continued to push forward on investigating the structure and evolution of the universe. He’s been a leader in emphasizing a curious disagreement that threatens to grow into a crisis: incompatible values of the Hubble constant (expansion rate of the universe) obtained from the cosmic microwave background vs. direct measurements. We talk about where this “Hubble tension” comes from, and what it might mean for the universe.

Astronomers rocked the cosmological world with the 1998 discovery that the universe is accelerating. Well-deserved Nobel Prizes were awarded to Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, and today’s guest Adam Riess. Adam has continued to push forward on investigating the structure and evolution of the universe. He’s been a leader in emphasizing a curious disagreement that threatens to grow into a crisis: incompatible values of the Hubble constant (expansion rate of the universe) obtained from the cosmic microwave background vs. direct measurements. We talk about where this “Hubble tension” comes from, and what it might mean for the universe. The period since the global financial crisis has seen increased recognition, sparked in particular by the

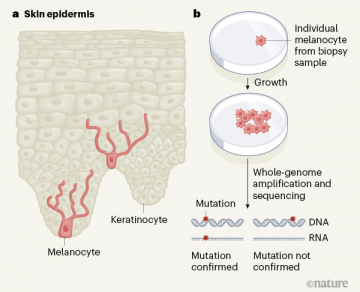

The period since the global financial crisis has seen increased recognition, sparked in particular by the  Mutations occur in our cells throughout life. Although most mutations are harmless, they accumulate in number in our tissues as we age, and if they arise in key genes, they can alter cellular behaviour and set cells on a path towards cancer. There is also speculation that somatic mutations (those in non-reproductive tissues) might contribute to ageing and to diseases unrelated to cancer. However, technical difficulties in detecting the mutations present in a small number of cells, or even in single cells, have hampered research and limited progress in understanding the first steps in cancer development and the impact of somatic mutation on ageing and disease.

Mutations occur in our cells throughout life. Although most mutations are harmless, they accumulate in number in our tissues as we age, and if they arise in key genes, they can alter cellular behaviour and set cells on a path towards cancer. There is also speculation that somatic mutations (those in non-reproductive tissues) might contribute to ageing and to diseases unrelated to cancer. However, technical difficulties in detecting the mutations present in a small number of cells, or even in single cells, have hampered research and limited progress in understanding the first steps in cancer development and the impact of somatic mutation on ageing and disease.  On September 14, 2011, we awoke once again to the image of two bodies hanging from a bridge. One man, one woman. He, tied by the hands. She, by the wrists and ankles. Just like so many other similar occurrences, and as noted in newspaper articles with a certain amount of trepidation, the bodies showed signs of having been tortured. Entrails erupted from the woman’s abdomen, opened in three different places.

On September 14, 2011, we awoke once again to the image of two bodies hanging from a bridge. One man, one woman. He, tied by the hands. She, by the wrists and ankles. Just like so many other similar occurrences, and as noted in newspaper articles with a certain amount of trepidation, the bodies showed signs of having been tortured. Entrails erupted from the woman’s abdomen, opened in three different places. The hallmarks of the Buddy Bolden myth go something like this: in the whispery pre-jazz world of turn of the twentieth century New Orleans, one titanic musical presence loomed larger than any – Bolden, the Paul Bunyan of the cornet. He played louder, harder, and hotter than any horn player before, or since. Unlike the ensembles led by his contemporaries, most or all of whom read printed sheet music on the bandstand, Bolden’s band was primarily made up of “ear” players. They were among the first (some claim the first) to bring the art of improvisation to the kinds of ensembles that preceded the advent of the musical style we now call jazz – mostly string bands and small orchestras performing marches, hymns, rags, and popular songs of the day. No recordings of Bolden and his band exist, though an unverified story persists that he made at least one Edison wax cylinder that has never been found – the Holy Grail of early jazz. But the legend that’s been handed down is that Bolden’s playing and his ability to read and draw from the energy of his adoring, excitable audiences was radical, incendiary, and transgressive.

The hallmarks of the Buddy Bolden myth go something like this: in the whispery pre-jazz world of turn of the twentieth century New Orleans, one titanic musical presence loomed larger than any – Bolden, the Paul Bunyan of the cornet. He played louder, harder, and hotter than any horn player before, or since. Unlike the ensembles led by his contemporaries, most or all of whom read printed sheet music on the bandstand, Bolden’s band was primarily made up of “ear” players. They were among the first (some claim the first) to bring the art of improvisation to the kinds of ensembles that preceded the advent of the musical style we now call jazz – mostly string bands and small orchestras performing marches, hymns, rags, and popular songs of the day. No recordings of Bolden and his band exist, though an unverified story persists that he made at least one Edison wax cylinder that has never been found – the Holy Grail of early jazz. But the legend that’s been handed down is that Bolden’s playing and his ability to read and draw from the energy of his adoring, excitable audiences was radical, incendiary, and transgressive.