Adam S. Green in the Journal of Archaeological Research (h/t Jain Family Institute):

Adam S. Green in the Journal of Archaeological Research (h/t Jain Family Institute):

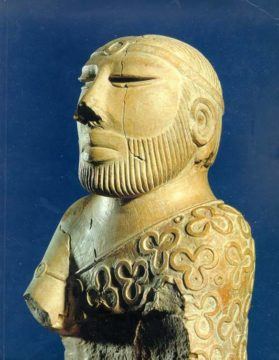

The archaeologists who first investigated the Indus civilization thought it diverged sharply from contemporary societies in Egypt and Mesopotamia (Marshall 1931, p. xi). For nearly a century, archaeologists have made a concerted effort to close this gap and make the Indus seem more “normal” in comparison with other complex societies. This is especially true with respect to inequality—specifically, stratification in the distribution of wealth and hierarchies of political power. In my view, these efforts have been largely unsuccessful. Marshall’s observation was basically correct; attempts to refute it have been based on the theoretical assumption that all social complexity entails stratified social relations, rather than a critical interpretation of the empirical evidence. I argue that the widespread distribution of production activities and wealth in Indus cities indicates that the stratification of wealth and power, particularly in the hands of a ruling class who monopolized resources and dictated the production activities of everyone else, was absent from the Indus civilization.

Indus cities (c. 2600–1900 BC) were expansive and planned, with large-scale architecture and sophisticated early technologies—writing, metallurgy, weights and measures, and seals—that matched those from contemporaneous societies in Egypt and Mesopotamia. And yet, it has long been noted that Indus cities lack the tombs, palaces, and aggrandizing art that characterize other early complex societies (e.g., Fairservis 1967). These lines of evidence are essential to the comparative study of complex societies and particularly to the analysis of past inequalities in wealth and power (e.g., Feinman 1995; Feinman and Marcus 1998; Smith 2012). Their absence in the Indus suggests that the forms of inequality that we would expect to find if a class of ruling nobles managed society were limited or absent in Indus cities. Given that complex societies have often been defined by the presence of such stratification (e.g., Trigger 2003, p. 46), the perception that the absence of a ruling class in the Indus civilization risked its omission from comparative debates about the emergence of social complexity gained ground. In response, there arose an implicit argument that the Indus was indeed exceptional, not because it lacked a ruling class, but because to fully appreciate its political economy required an exceptional set of criteria (e.g., Kenoyer 1998).

More here.

Steve Hahn in Boston Review:

Steve Hahn in Boston Review: Dilip Hiro in The Nation:

Dilip Hiro in The Nation: Philip Roth

Philip Roth Seth Rogen’s home sits on several wooded acres in the hills above Los Angeles, under a canopy of live oak and eucalyptus trees strung with outdoor pendants that light up around dusk, when the frogs on the grounds start croaking. I pulled up at the front gate on a recent afternoon, and Rogen’s voice rumbled through the intercom. “Hellooo!” He met me at the bottom of his driveway, which is long and steep enough that he keeps a golf cart up top “for schlepping big things up the driveway that are too heavy to walk,” he said, adding, as if bashful about coming off like the kind of guy who owns a dedicated driveway golf cart, “It doesn’t get a ton of use.” Rogen wore a beard, chinos, a cardigan from the Japanese brand Needles and Birkenstocks with marled socks — laid-back Canyon chic. He led me to a switchback trail cut into a hillside, which we climbed to a vista point. Below us was Rogen’s office; the house he shares with his wife, Lauren, and their 11-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Zelda; and the converted garage where they make pottery. I was one of the first people, it turns out, to see the place. “I haven’t had many people over,” Rogen said, “because we moved in during the pandemic.”

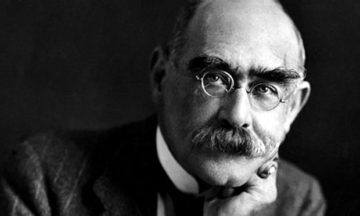

Seth Rogen’s home sits on several wooded acres in the hills above Los Angeles, under a canopy of live oak and eucalyptus trees strung with outdoor pendants that light up around dusk, when the frogs on the grounds start croaking. I pulled up at the front gate on a recent afternoon, and Rogen’s voice rumbled through the intercom. “Hellooo!” He met me at the bottom of his driveway, which is long and steep enough that he keeps a golf cart up top “for schlepping big things up the driveway that are too heavy to walk,” he said, adding, as if bashful about coming off like the kind of guy who owns a dedicated driveway golf cart, “It doesn’t get a ton of use.” Rogen wore a beard, chinos, a cardigan from the Japanese brand Needles and Birkenstocks with marled socks — laid-back Canyon chic. He led me to a switchback trail cut into a hillside, which we climbed to a vista point. Below us was Rogen’s office; the house he shares with his wife, Lauren, and their 11-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Zelda; and the converted garage where they make pottery. I was one of the first people, it turns out, to see the place. “I haven’t had many people over,” Rogen said, “because we moved in during the pandemic.” It is always tricky writing about Kipling. By the time of his death in 1936 his jingoism, with its babble about the “white man’s burden” in Africa, made many moderate souls feel queasy. Batchelor is too scrupulous a scholar to ignore what came after the Just So Stories – indeed he points out that within two years of the book’s publication the satirist Max Beerbohm was drawing Kipling as an imperial stooge, the diminutive bugle-blowing cockney lover of a blousy-looking Britannia.

It is always tricky writing about Kipling. By the time of his death in 1936 his jingoism, with its babble about the “white man’s burden” in Africa, made many moderate souls feel queasy. Batchelor is too scrupulous a scholar to ignore what came after the Just So Stories – indeed he points out that within two years of the book’s publication the satirist Max Beerbohm was drawing Kipling as an imperial stooge, the diminutive bugle-blowing cockney lover of a blousy-looking Britannia. The evenhanded approach of

The evenhanded approach of  I thought I was so clever. For a few days, anyway.

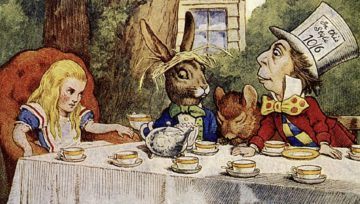

I thought I was so clever. For a few days, anyway. The first numbers that come to mind when thinking about Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland might be how much money the movie is raking in at the box office.

The first numbers that come to mind when thinking about Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland might be how much money the movie is raking in at the box office. I would like to stage a fight between two different accounts of the current political landscape—what’s been called the “post-truth” era, the infodemic, the end of democracy, or perhaps most accurately, the total shitshow of the now.

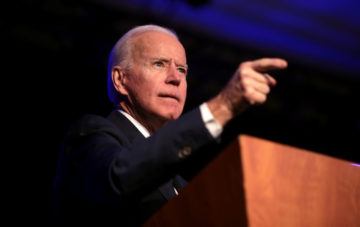

I would like to stage a fight between two different accounts of the current political landscape—what’s been called the “post-truth” era, the infodemic, the end of democracy, or perhaps most accurately, the total shitshow of the now. “W

“W “It feels like a grew a new heart.” That’s what my best friend told me the day her daughter was born. Back then, I rolled my eyes at her new-mom corniness. But ten years and three kids of my own later, Emily’s words drift back to me as I ride a crammed elevator up to a laboratory in New York City’s

“It feels like a grew a new heart.” That’s what my best friend told me the day her daughter was born. Back then, I rolled my eyes at her new-mom corniness. But ten years and three kids of my own later, Emily’s words drift back to me as I ride a crammed elevator up to a laboratory in New York City’s  A

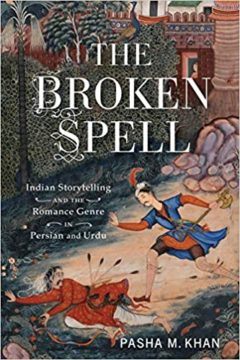

A  With the vanishing of the name goes the disappearance of the object, the slice of art, the fragment of literature, the portion of music. With the fading of the thing, so the name is gradually effaced from memory, and whatever there was becomes anonymous.

With the vanishing of the name goes the disappearance of the object, the slice of art, the fragment of literature, the portion of music. With the fading of the thing, so the name is gradually effaced from memory, and whatever there was becomes anonymous.