Jonathan O’Callaghan in Quanta:

The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities.

The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities.

Seen in this way, the inexorable rise in entropy, or disorder, as quantified by the second law of thermodynamics, takes on an almost mathematical certainty. So of course physicists are constantly trying to break it.

One almost did. A thought experiment devised by the Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1867 stumped scientists for 115 years. And even after a solution was found, physicists have continued to use “Maxwell’s demon” to push the laws of the universe to their limits.

More here.

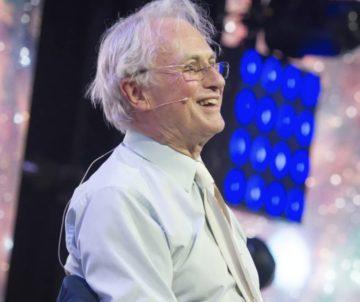

Last week, the American Humanist Association (AHA) stripped British author Richard Dawkins of his 1996 Humanist of the Year award after he made a comment on Twitter that offended some in the transgender community.

Last week, the American Humanist Association (AHA) stripped British author Richard Dawkins of his 1996 Humanist of the Year award after he made a comment on Twitter that offended some in the transgender community. How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans.

How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans. Born in 1872, Teffi was a contemporary of Alexander Blok and other leading Russian Symbolists. Her own poetry is derivative, but in her prose she shows a remarkable gift for grounding Symbolist themes and imagery in the everyday world. “The Heart” is entirely realistic and at times even gossipy—yet the story is permeated throughout with Christian symbolism relating to fish. In “A Quiet Backwater,” she achieves a still more successful synthesis of the heavenly and the earthly. Toward the end of this seven-page story a laundress gives a long disquisition on the name days of various birds, insects, and animals. The mare, the bee, the glowworm—she tells a young visitor—all have their name days. And so does the earth herself: “And the Feast of the Holy Ghost is the name day of the earth herself. On this day, no one dairnst disturb the earth. No diggin, or sowin—not even flower pickin, or owt. No buryin t’ dead. Great sin it is, to upset the earth on ’er name day. Aye, even beasts understand. On that day, they dairnst lay a claw, nor a hoof, nor a paw on the earth. Great sin, yer see.” In a key poem—almost a manifesto—of French Symbolism, Charles Baudelaire interprets the whole world as a web of mystical “correspondences.” In a less grandiose way, Teffi conveys a similar vision. She was, I imagine, delighted by the paradox of the earth’s name day being the Feast of the Holy Spirit—not, as one might expect, the feast of a saint associated with some activity like plowing.

Born in 1872, Teffi was a contemporary of Alexander Blok and other leading Russian Symbolists. Her own poetry is derivative, but in her prose she shows a remarkable gift for grounding Symbolist themes and imagery in the everyday world. “The Heart” is entirely realistic and at times even gossipy—yet the story is permeated throughout with Christian symbolism relating to fish. In “A Quiet Backwater,” she achieves a still more successful synthesis of the heavenly and the earthly. Toward the end of this seven-page story a laundress gives a long disquisition on the name days of various birds, insects, and animals. The mare, the bee, the glowworm—she tells a young visitor—all have their name days. And so does the earth herself: “And the Feast of the Holy Ghost is the name day of the earth herself. On this day, no one dairnst disturb the earth. No diggin, or sowin—not even flower pickin, or owt. No buryin t’ dead. Great sin it is, to upset the earth on ’er name day. Aye, even beasts understand. On that day, they dairnst lay a claw, nor a hoof, nor a paw on the earth. Great sin, yer see.” In a key poem—almost a manifesto—of French Symbolism, Charles Baudelaire interprets the whole world as a web of mystical “correspondences.” In a less grandiose way, Teffi conveys a similar vision. She was, I imagine, delighted by the paradox of the earth’s name day being the Feast of the Holy Spirit—not, as one might expect, the feast of a saint associated with some activity like plowing. Disney’s 2019 remake of its 1994 classic “The Lion King” was a box-office success, grossing more than one and a half billion dollars. But it was also, in some ways, a failed experiment. The film’s photo-realistic, computer-generated animals spoke with the rich, complex voices of actors such as Donald Glover and Chiwetel Ejiofor—and many viewers found it hard to reconcile the complex intonations of those voices with the feline gazes on the screen. In giving such persuasively nonhuman animals human personalities and thoughts, the film created a kind of cognitive dissonance. It had been easier to imagine the interiority of the stylized beasts in the original film. Disney’s filmmakers had stumbled onto an issue that has long fascinated philosophers and zoologists: the gap between animal minds and our own. The dream of bridging that divide, perhaps by speaking with and understanding animals, goes back to antiquity. Solomon was said to have possessed a ring that gave him the power to converse with beasts—a legend that furnished the title of the ethologist Konrad Lorenz’s pioneering book on animal psychology, “

Disney’s 2019 remake of its 1994 classic “The Lion King” was a box-office success, grossing more than one and a half billion dollars. But it was also, in some ways, a failed experiment. The film’s photo-realistic, computer-generated animals spoke with the rich, complex voices of actors such as Donald Glover and Chiwetel Ejiofor—and many viewers found it hard to reconcile the complex intonations of those voices with the feline gazes on the screen. In giving such persuasively nonhuman animals human personalities and thoughts, the film created a kind of cognitive dissonance. It had been easier to imagine the interiority of the stylized beasts in the original film. Disney’s filmmakers had stumbled onto an issue that has long fascinated philosophers and zoologists: the gap between animal minds and our own. The dream of bridging that divide, perhaps by speaking with and understanding animals, goes back to antiquity. Solomon was said to have possessed a ring that gave him the power to converse with beasts—a legend that furnished the title of the ethologist Konrad Lorenz’s pioneering book on animal psychology, “ It might seem surprising that origami, the ancient Japanese art of paper folding, is an integral part of engineering. However, origami structures can be folded up compactly and deployed at the nano- and macroscales seemingly without effort. They are therefore well suited for a wide range of applications, including robotics

It might seem surprising that origami, the ancient Japanese art of paper folding, is an integral part of engineering. However, origami structures can be folded up compactly and deployed at the nano- and macroscales seemingly without effort. They are therefore well suited for a wide range of applications, including robotics

They are invisible at first. In their Southeast Asian forest homes, they grow as thin strands of cells, foreign fibers sometimes more than 10 meters long that weave through the vital tissues of their vine hosts, siphoning nourishment from them. Even under a microscope, the single-file lines of cells are nearly indistinguishable from the vine’s own. They seem more like a fungus than a plant.

They are invisible at first. In their Southeast Asian forest homes, they grow as thin strands of cells, foreign fibers sometimes more than 10 meters long that weave through the vital tissues of their vine hosts, siphoning nourishment from them. Even under a microscope, the single-file lines of cells are nearly indistinguishable from the vine’s own. They seem more like a fungus than a plant. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not likely to make humans redundant. Nor will it

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not likely to make humans redundant. Nor will it  Postcolonial literature brings together writings from formerly colonised territories, allowing commonalities across disparate cultures to be identified and examined. Here, the University of Toronto academic Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb recommends five key works that explore philosophical and political questions through allegory, personal reflection and powerful polemic.

Postcolonial literature brings together writings from formerly colonised territories, allowing commonalities across disparate cultures to be identified and examined. Here, the University of Toronto academic Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb recommends five key works that explore philosophical and political questions through allegory, personal reflection and powerful polemic. In high school, one of author Jess Zimmerman’s Internet usernames was Medusa. A self-described mythology nerd, her childhood copy of “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths” was well-worn. But as she recalls in her scorching collection of essays, “Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology,” she particularly identified with the snake-haired creature whose power originated in ugliness: The mere sight of Medusa could turn a man to stone. As a teenager who was profoundly insecure about her looks, Zimmerman writes that calling herself Medusa was “an attempt to recuse myself from the game of human attraction before anyone pointed out that I’d already lost.”

In high school, one of author Jess Zimmerman’s Internet usernames was Medusa. A self-described mythology nerd, her childhood copy of “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths” was well-worn. But as she recalls in her scorching collection of essays, “Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology,” she particularly identified with the snake-haired creature whose power originated in ugliness: The mere sight of Medusa could turn a man to stone. As a teenager who was profoundly insecure about her looks, Zimmerman writes that calling herself Medusa was “an attempt to recuse myself from the game of human attraction before anyone pointed out that I’d already lost.” The pandemic is sweeping through India at a pace that has staggered scientists. Daily case numbers have exploded since early March: the government reported 273,810 new infections nationally on 18 April. High numbers in India have also helped drive global cases to a daily high of 854,855 in the past week, almost breaking a record set in January. Just months earlier, antibody data had suggested that many people in cities such as Delhi and Chennai had already been infected, leading some researchers to conclude that the worst of the pandemic

The pandemic is sweeping through India at a pace that has staggered scientists. Daily case numbers have exploded since early March: the government reported 273,810 new infections nationally on 18 April. High numbers in India have also helped drive global cases to a daily high of 854,855 in the past week, almost breaking a record set in January. Just months earlier, antibody data had suggested that many people in cities such as Delhi and Chennai had already been infected, leading some researchers to conclude that the worst of the pandemic