Jennifer Wilson in The Nation:

Jennifer Wilson in The Nation:

The thing about big plans is that they require people to carry them out. The problem of personnel particularly plagued Peter the Great. Convinced by his European advisers that his country was backward and stuck in a medieval mindset, he spent much of his reign on a series of modernizing initiatives intended to get Russia “caught up” with the West. To implement his reforms—which included establishing a navy, imposing a tax on beards, and eventually drafting half a million serfs to build a city (named after himself) on nothing but marshland—he needed a robust bureaucracy and a standing military that could manage the demands of his new, spruced-up empire. Peter thus made service—civil or military—compulsory for the Russian nobility, and he implemented a new class system, the Table of Ranks, under which one could be promoted according to how long and how well one served.

The Table of Ranks included 14 classes, from collegiate registrars (which included lowly copy clerks) at the very bottom to the top civil rank of chancellor. While it was pitched as the introduction of a modern meritocratic system in Russia, in practice the table produced sharp class divisions, prevented people from working in fields that did not correspond to their rank, and tied social status to the name and nature of one’s profession. A version of this system continued in Russia all the way up to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and yet, in much of the literature of the 19th century, the civil service—which structured almost every aspect of life, particularly in the capital of St. Petersburg—feels weirdly merged into the background, more a fact of life than a facet of literary fiction, save for in the work of one writer: Nikolai Gogol.

More here.

Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB: F

F Early in her career, Alison Bechdel, then a cult cartoonist — “at the pinnacle of my bitterness,” she would later say — was invited to contribute to a special gay pride issue of Seattle’s alternative newspaper The Stranger. She fired off a comic strip titled “Oppressed Minority Cartoonist.” She drew herself at her desk, flanked by a bottle of Scotch, mid-tirade. Why had her work been pigeonholed? And why had she complied so willingly, chronicling only lesbians, her “oppressed minority group”? In the last panel, her rant is interrupted by a phone call inviting her to contribute to that very gay pride issue. “I’d be honored,” she capitulates.

Early in her career, Alison Bechdel, then a cult cartoonist — “at the pinnacle of my bitterness,” she would later say — was invited to contribute to a special gay pride issue of Seattle’s alternative newspaper The Stranger. She fired off a comic strip titled “Oppressed Minority Cartoonist.” She drew herself at her desk, flanked by a bottle of Scotch, mid-tirade. Why had her work been pigeonholed? And why had she complied so willingly, chronicling only lesbians, her “oppressed minority group”? In the last panel, her rant is interrupted by a phone call inviting her to contribute to that very gay pride issue. “I’d be honored,” she capitulates. To get this out of the way: Destroying the coronavirus is, without question, paramount. Millions of people are dead, and tens of thousands more die every week. At the same time, the majority of the trillions of microbes that inhabit our skin and gut—collectively, our microbiome—are either

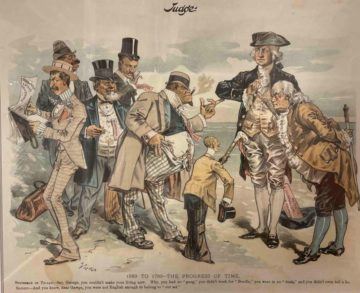

To get this out of the way: Destroying the coronavirus is, without question, paramount. Millions of people are dead, and tens of thousands more die every week. At the same time, the majority of the trillions of microbes that inhabit our skin and gut—collectively, our microbiome—are either  Few documents are venerated as much as the American constitution. Until recently, one million people a year filed past the original copy on display in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in Washington DC. Yet, as Linda Colley’s brilliant new book shows, viewing constitutions as national tablets of stone tells us more about their contemporary charisma than the complex histories from which they were wrought. In this compelling study of constitutions produced around the world between the mid-18th century and the outbreak of the first world war, she upends the familiar version of history at every turn. Out goes the myth that constitutions were the product of democratic aspirations or revolution – rather they arose from the ashes of war or the threat of invasion. Nations may have been girded by constitutional documents, but these were borderless texts, available for adaptation across time and space. Above all, constitutions were “protean and volatile pieces of technology” that travelled far and wide, assisted by the expansion of print media and the speeding-up of long-distance travel and communication.

Few documents are venerated as much as the American constitution. Until recently, one million people a year filed past the original copy on display in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in Washington DC. Yet, as Linda Colley’s brilliant new book shows, viewing constitutions as national tablets of stone tells us more about their contemporary charisma than the complex histories from which they were wrought. In this compelling study of constitutions produced around the world between the mid-18th century and the outbreak of the first world war, she upends the familiar version of history at every turn. Out goes the myth that constitutions were the product of democratic aspirations or revolution – rather they arose from the ashes of war or the threat of invasion. Nations may have been girded by constitutional documents, but these were borderless texts, available for adaptation across time and space. Above all, constitutions were “protean and volatile pieces of technology” that travelled far and wide, assisted by the expansion of print media and the speeding-up of long-distance travel and communication.

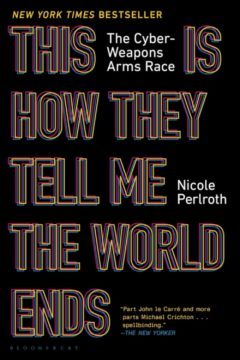

Sometime in mid-2009

Sometime in mid-2009 An outbreak the size of India’s second wave, apparently fuelled by Covid-19 variants that appear to be more infectious than earlier strains, would have overwhelmed most public health systems – let alone one of the

An outbreak the size of India’s second wave, apparently fuelled by Covid-19 variants that appear to be more infectious than earlier strains, would have overwhelmed most public health systems – let alone one of the  TRUST THE SCIENCE, we’re told. Wear masks! Science says so! These injunctions are likely to induce a couple of reflex responses. On the one hand, saying that you are in favor of Science — I’ll keep it capitalized for now — is somewhat like saying that you are all for oxygen and cute puppies and pleasant strolls. It is so straightforward as to be anodyne. But then there is the counter-reflex, with the “pro-Science” mantra sounding like a liberal shibboleth, and the Republican Party (or its voters) cast as Those Who Don’t Trust Science. Recent

TRUST THE SCIENCE, we’re told. Wear masks! Science says so! These injunctions are likely to induce a couple of reflex responses. On the one hand, saying that you are in favor of Science — I’ll keep it capitalized for now — is somewhat like saying that you are all for oxygen and cute puppies and pleasant strolls. It is so straightforward as to be anodyne. But then there is the counter-reflex, with the “pro-Science” mantra sounding like a liberal shibboleth, and the Republican Party (or its voters) cast as Those Who Don’t Trust Science. Recent  Nearly every day while writing my new book,

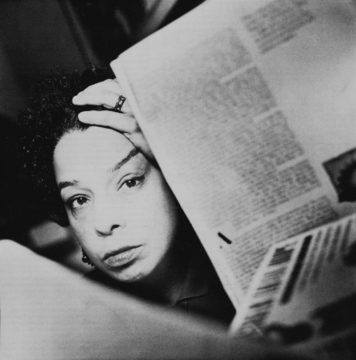

Nearly every day while writing my new book,  There are many reasons Mala’ika’s work has largely evaded the West. It’s hard to pigeonhole her, for one thing, which is by her own design. Mala’ika was always a neither-here-nor-there kind of poet. She was an Easterner with a calculated reverence for the West, a bard of Occidental impulses in a time and place more accustomed to Orientalist ones. She went from being a student of English poetry to being a scholar of it while simultaneously establishing herself as a thoroughly Arab poet. She was also an innovator whose free verse remains accessible while still keeping within her larger cultural tradition. And her feminism specifically concerned the roles of Arab women without evincing a need to compare, or center, the lives of her Western counterparts, as many women poets in her generation and beyond were tempted to do. (Mala’ika, with little fanfare, studied at Princeton in the 1950s, when it was still an all-male university.) She was also, finally, of the modernist and postmodernist eras but is perhaps best classified as a Romantic poet, despite publishing nearly a century after that movement’s heyday. As Drumsta notes in her substantial introduction, all these facts have perplexed Mala’ika’s biographers and translators.

There are many reasons Mala’ika’s work has largely evaded the West. It’s hard to pigeonhole her, for one thing, which is by her own design. Mala’ika was always a neither-here-nor-there kind of poet. She was an Easterner with a calculated reverence for the West, a bard of Occidental impulses in a time and place more accustomed to Orientalist ones. She went from being a student of English poetry to being a scholar of it while simultaneously establishing herself as a thoroughly Arab poet. She was also an innovator whose free verse remains accessible while still keeping within her larger cultural tradition. And her feminism specifically concerned the roles of Arab women without evincing a need to compare, or center, the lives of her Western counterparts, as many women poets in her generation and beyond were tempted to do. (Mala’ika, with little fanfare, studied at Princeton in the 1950s, when it was still an all-male university.) She was also, finally, of the modernist and postmodernist eras but is perhaps best classified as a Romantic poet, despite publishing nearly a century after that movement’s heyday. As Drumsta notes in her substantial introduction, all these facts have perplexed Mala’ika’s biographers and translators. Nothing but the Music, which collects verse written between 1974 and 1992, reasserts Davis’s centrality to the Black Arts and Black Feminist movements. Though the book covers a wide range of topics, all the poems engage with music: listening to it, composing it, being transformed by it. There are accounts of driving through a rainstorm to see the Commodores, descriptions of Senegalese seamstresses listening to jazz as they work, and visions of enslaved people singing during the Middle Passage. Davis employs a variety of stanza forms, though most of the poems are on the shorter side. “Many of these poems here were performed with a number of musicians in different improvising configurations,” she writes in the acknowledgments. Her collaborators include her late husband and composer Joseph Jarman, free jazz pioneer Cecil Taylor, and saxophonist Arthur Blythe.

Nothing but the Music, which collects verse written between 1974 and 1992, reasserts Davis’s centrality to the Black Arts and Black Feminist movements. Though the book covers a wide range of topics, all the poems engage with music: listening to it, composing it, being transformed by it. There are accounts of driving through a rainstorm to see the Commodores, descriptions of Senegalese seamstresses listening to jazz as they work, and visions of enslaved people singing during the Middle Passage. Davis employs a variety of stanza forms, though most of the poems are on the shorter side. “Many of these poems here were performed with a number of musicians in different improvising configurations,” she writes in the acknowledgments. Her collaborators include her late husband and composer Joseph Jarman, free jazz pioneer Cecil Taylor, and saxophonist Arthur Blythe.