One of the Citizens

What we have here is a mechanic who reads Nietzsche,

who talks of the English and the French Romantics

as he grinds the pistons; who takes apart the Christians

as he plunges the tarred sprockets and gummy bolts

into the mineral spirits that have numbed his fingers;

an existentialist who dropped out of school to enlist,

who lied and said he was eighteen, who gorged himself

all afternoon with cheese and bologna to make the weight

and guarded a Korean hill before he roofed houses,

first in East Texas, the here in North Alabama. Now

his work is logic and the sure memory of disassembly.

As he dismantles the engine, he will point out damage

and use, the bent nuts, the worn shims of uneasy agreement.

He will show you the scar behind each ear where they

put the plates. He will tap his head like a kettle

where the shrapnel hit, and now history leaks from him,

the slow guile of diplomacy and the gold war makes,

betrayal at Yalta and the barbed wall circling Berlin.

As he sharpens the blades, he will whisper Ruby and Ray.

As he adjusts the carburetors, he will tell you

of finer carburetors, invented in Omaha, killed by Detroit,

of deals that fall like dice in the world’s casinos,

and of the commission in New York that runs everything.

Despiser of miracles, of engineers, he is as drawn

by conspiracies as his wife by the gossip of princesses,

and he longs for the definitive payola of the ultimate fix.

He will not mention the fiddle, though he played it once

in a room where farmers spun and curses were flung,

or the shelter he gouged in the clay under the kitchen.

He is the one who married early, who marshaled a crew

of cranky half-criminal boys through the incompletions,

digging ditches, setting forms for culverts and spillways

for miles along the right-of-way of the interstate;

who moved from construction to Goodyear Rubber

when the roads were finished; who quit each job because

he could not bear the bosses after he had read Kafka;

who, in his mid-forties, gave up on Sartre and Camus

and set up shop in his Quonset hut behind the welder,

repairing what comes to him, rebuilding the small engines

of lawn mowers and outboards. And what he likes best

is to break it all down, to spread it out around him

like a picnic, and to find not just what’s wrong

but what’s wrong and interesting — some absurd vanity,

or work, that is its own meaning — so when it’s together

again and he’s fired it with an easy pull of the cord,

he will almost hear himself speaking, as the steel

clicks in the single cylinder, in a language almost

like German, clean and merciless, beyond good and evil.

by Rodney Jones

from Transparent Gestures

Haughton Mifflin, 1989

There are many ways to understand the tendency roiling liberal-democratic politics in recent years, from the outcome of the Brexit vote and the presidency of Donald Trump to the surge in support for antiliberal politicians and parties across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. It’s been variously described as an explosion of right-wing populism, a resurgence of nationalism, a renewed flowering of xenophobia and racism, even a rebirth of fascism. But what all of these theories are striving to explain is a pervasive collapse of faith in multiculturalism as an organizing principle of free societies.

There are many ways to understand the tendency roiling liberal-democratic politics in recent years, from the outcome of the Brexit vote and the presidency of Donald Trump to the surge in support for antiliberal politicians and parties across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. It’s been variously described as an explosion of right-wing populism, a resurgence of nationalism, a renewed flowering of xenophobia and racism, even a rebirth of fascism. But what all of these theories are striving to explain is a pervasive collapse of faith in multiculturalism as an organizing principle of free societies.

Kink, a new anthology of short fiction edited by R. O. Kwon and Garth Greenwell, intends to “[c]lose some of the distances between our solitudes” by collecting kinky sex-centered stories written by 15 authors of different races, sexual orientations, gender identities, and ethnicities. A quick look at the writers’ bios, though, shows how remarkably alike they are. Five of them graduated from, or currently teach at, the University of Iowa’s MFA program. Almost all are famous in the world of contemporary literary fiction — in addition to the editors, Kink’s contributors include Roxane Gay, Chris Kraus, Carmen Maria Machado, Alexander Chee, and Brandon Taylor. The kink, too, is pretty one-note. There’s a lot of BDSM, most of it light: boot-licking, choking, spitting, and slapping.

Kink, a new anthology of short fiction edited by R. O. Kwon and Garth Greenwell, intends to “[c]lose some of the distances between our solitudes” by collecting kinky sex-centered stories written by 15 authors of different races, sexual orientations, gender identities, and ethnicities. A quick look at the writers’ bios, though, shows how remarkably alike they are. Five of them graduated from, or currently teach at, the University of Iowa’s MFA program. Almost all are famous in the world of contemporary literary fiction — in addition to the editors, Kink’s contributors include Roxane Gay, Chris Kraus, Carmen Maria Machado, Alexander Chee, and Brandon Taylor. The kink, too, is pretty one-note. There’s a lot of BDSM, most of it light: boot-licking, choking, spitting, and slapping.

Who wrote the Declaration of Independence? Thomas Jefferson is generally credited as its author, but Akhil Reed Amar believes there’s a better answer. “America did,” Amar argues in “The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840.”

Who wrote the Declaration of Independence? Thomas Jefferson is generally credited as its author, but Akhil Reed Amar believes there’s a better answer. “America did,” Amar argues in “The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840.” The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures to

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures to

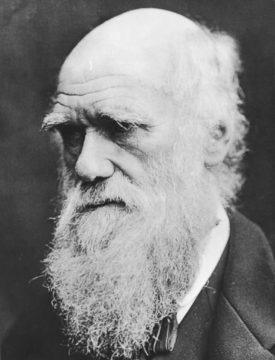

Last week the prestigious and normally staid journal Science kicked up a fuss by running a short essay on Charles Darwin that provoked the anti-woke.

Last week the prestigious and normally staid journal Science kicked up a fuss by running a short essay on Charles Darwin that provoked the anti-woke. President

President  Wait, not another book about the Beatles? Surely that story’s bones have been picked clean by now? What saves One Two Three Four from being just another Beatles indulgathon is how the author has reworked the standard biography template. His take is a seductive miscellany of essays, insider accounts, opinions, flight-of-fancy yarns, and more. Much of it is sourced from already published material but Brown also includes his own opinions and anecdotes. Somehow he has managed to create a uniquely fresh perceptive on a well-worn story.

Wait, not another book about the Beatles? Surely that story’s bones have been picked clean by now? What saves One Two Three Four from being just another Beatles indulgathon is how the author has reworked the standard biography template. His take is a seductive miscellany of essays, insider accounts, opinions, flight-of-fancy yarns, and more. Much of it is sourced from already published material but Brown also includes his own opinions and anecdotes. Somehow he has managed to create a uniquely fresh perceptive on a well-worn story. “FILING FOR DIVORCE,”

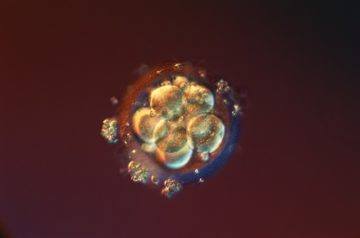

“FILING FOR DIVORCE,”  The international body representing stem-cell scientists has torn up a decades-old limit on the length of time that scientists should grow human embryos in the lab, giving more leeway to researchers who are studying human development and disease. Previously, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommended that scientists culture human embryos for no more than two weeks after fertilization. But on 26 May, the society said it was relaxing this famous limit, known as the ‘14-day rule’. Rather than replace or extend the limit, the ISSCR now suggests that studies proposing to grow human embryos beyond the two-week mark be considered on a case-by-case basis, and be subjected to several phases of review to determine at what point the experiments must be stopped.

The international body representing stem-cell scientists has torn up a decades-old limit on the length of time that scientists should grow human embryos in the lab, giving more leeway to researchers who are studying human development and disease. Previously, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommended that scientists culture human embryos for no more than two weeks after fertilization. But on 26 May, the society said it was relaxing this famous limit, known as the ‘14-day rule’. Rather than replace or extend the limit, the ISSCR now suggests that studies proposing to grow human embryos beyond the two-week mark be considered on a case-by-case basis, and be subjected to several phases of review to determine at what point the experiments must be stopped. George Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stewart Mill, and even pre-empted elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick.

George Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stewart Mill, and even pre-empted elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick. A surrealist and existentialist tale, The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected by several publishers, but the novel found an afterlife via a series of winding roads. The rejections led Wright to condense the narrative, in particular cutting the lengthy description of police violence in the novel’s opening, and turn it into a short story that was published in 1944. That story was admired by Wright’s friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison. Later, after winning the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, Ellison stated that his novel had been inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. While he and Wright had fallen out by this time, Wright’s influence on the novel was hard to deny. Despite this fact, Invisible Man entered the American literary canon, while Wright’s story languished in obscurity. In the popular imagination, he became known as the author of Native Son, Black Boy, and (for those interested in anti-colonialism) The Color Curtain, but not as the originator of invisible men living underground. That honor remained Ellison’s.

A surrealist and existentialist tale, The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected by several publishers, but the novel found an afterlife via a series of winding roads. The rejections led Wright to condense the narrative, in particular cutting the lengthy description of police violence in the novel’s opening, and turn it into a short story that was published in 1944. That story was admired by Wright’s friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison. Later, after winning the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, Ellison stated that his novel had been inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. While he and Wright had fallen out by this time, Wright’s influence on the novel was hard to deny. Despite this fact, Invisible Man entered the American literary canon, while Wright’s story languished in obscurity. In the popular imagination, he became known as the author of Native Son, Black Boy, and (for those interested in anti-colonialism) The Color Curtain, but not as the originator of invisible men living underground. That honor remained Ellison’s. I am going to try to account for the reasons painters have consistently felt it OK to take note of the critiques aimed at the validity of their art form but almost always dismiss them in practice. A lot of what I have to say here is well-known in the mainly unspoken way things can get well-known. So I am trying to spell out what I think many people already know, and what I believe most painters do think.

I am going to try to account for the reasons painters have consistently felt it OK to take note of the critiques aimed at the validity of their art form but almost always dismiss them in practice. A lot of what I have to say here is well-known in the mainly unspoken way things can get well-known. So I am trying to spell out what I think many people already know, and what I believe most painters do think. One day last August, as they struggled to figure out whether to lift Covid-19 restrictions, the supervisors of Placer County, California, convened a panel of experts. It was a reasonable move. If being a local official could be thankless in normal times, the pandemic had made it nearly impossible. Federal messaging had been hopelessly muddled. Rules meant to stop viral spread came with painful side effects. One constituent insisted the sheriff enforce lockdowns; another called stay-at-home-orders an economic death sentence. Wanting advice from doctors and professors was hardly surprising.

One day last August, as they struggled to figure out whether to lift Covid-19 restrictions, the supervisors of Placer County, California, convened a panel of experts. It was a reasonable move. If being a local official could be thankless in normal times, the pandemic had made it nearly impossible. Federal messaging had been hopelessly muddled. Rules meant to stop viral spread came with painful side effects. One constituent insisted the sheriff enforce lockdowns; another called stay-at-home-orders an economic death sentence. Wanting advice from doctors and professors was hardly surprising.