From Harvard Magazine:

Harvard Medical School professor of neurology Rudolph Tanzi discusses how lifestyle choices can help maintain brain health during a person’s lifespan. Topics include Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia, the role of genetics and environment in health, and the importance of sleep, exercise, and diet in controlling neuroinflammation.

Harvard Medical School professor of neurology Rudolph Tanzi discusses how lifestyle choices can help maintain brain health during a person’s lifespan. Topics include Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia, the role of genetics and environment in health, and the importance of sleep, exercise, and diet in controlling neuroinflammation.

Jonathan Shaw: And how much of age-related cognitive decline is attributable to genetics, and how much to things that we could control potentially?

Rudolph Tanzi: It’s interesting, you know, this is what I wrote about in “Super Genes.” And I actually did congressional testimony on it, based on the books that I wrote, which was kind of interesting. And what I told them was, look, if you look at age-related diseases, like heart disease, Alzheimer’s, etc., you see a similar pattern. About 5 percent of the genes involved have very hard-hitting mutations—mutations that guarantee the disease, and usually with early onset. And usually those disease genes where you can’t do anything about them—they’re you know, they’re the rare ones—also tell you about the events that pathologically happen earliest in the disease. So, for example, you know, Brown and Goldstein won the Nobel Prize for finding a family with a rare mutation that gave them high cholesterol. And based on that, they proposed cholesterol had something to do with heart disease. And the first genes we found, you know, when I was a student at Harvard, for my doctoral thesis, I found the first Alzheimer’s gene. I named it amyloid precursor protein, APP, because it makes amyloid. And the mutations in that gene cause a rare form of early-onset Alzheimer’s with certainty, by making too much amyloid in the brain. And just like cholesterol, now we know amyloid is something that occurs in the brain a decade or two or three before symptoms. That’s when you have to hit it, just like cholesterol, you can’t wait to need to bypass to hit it. You have to hit it earlier. So it’s very analogous. Now, if you look at the other genetics of age-related diseases, the other 95 percent, you have genes with variations and mutations that predispose you to the disease, others that actually protect you from the disease, but none of them with certainty, at least not within a normal lifespan. So, you know, if you look at the early-onset Alzheimer genes we found that, you know, have mutations that guarantee the disease by 60 years old. Well, when lifespan was 50, those didn’t guarantee disease because you didn’t live long enough. And so some of the mutations we know now that predispose you to increased risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s, like the APOE4 variant is most common, you know, maybe when lifespan is 120 years old, that will be called completely penetrant. It’s going to guarantee the disease because you live long enough. So whenever you think about, does a gene mutation guarantee a disease? You have to think about how long you live, because some might just take longer to give you the disease. But based on how long we live right now, only 5 percent of Alzheimer’s genes guarantee the disease, 95 percent only predispose, which means lifestyle has a lot to do with avoiding this disease, which is why I wrote my books, which is why we have the McCance Center, because we want to teach people how to do their best to try to avoid this disease with lifestyle.

More here.

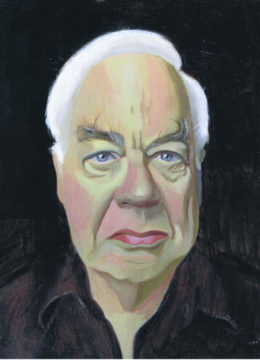

George Steiner was called many things across his lengthy writing career—sage, pedant, philosopher, snob, the last great European intellectual, a “mimic” staging a decades-long “impression of the world’s most learned man”—but the title he always claimed for himself was simply critic. As we reflect on the meaning of Steiner’s work in the wake of his death in February 2020, that self-characterization cannot be forgotten. Steiner was in many ways a formidable scholar, and his commentaries on core texts (Antigone, The Brothers Karamazov, the poetry of Paul Celan) and enduring themes (tragedy, translation, the inhuman) will surely be cited for many years to come. Yet from the beginning of his career in the late fifties to his last notable works at the turn of the century, he was explicitly engaged in the practice of criticism—the goal of which was to reach the wider republic of readers (not just academicians) with his urgent dispatches on the state of the arts and culture. It was as a critic that he asked to be judged.

George Steiner was called many things across his lengthy writing career—sage, pedant, philosopher, snob, the last great European intellectual, a “mimic” staging a decades-long “impression of the world’s most learned man”—but the title he always claimed for himself was simply critic. As we reflect on the meaning of Steiner’s work in the wake of his death in February 2020, that self-characterization cannot be forgotten. Steiner was in many ways a formidable scholar, and his commentaries on core texts (Antigone, The Brothers Karamazov, the poetry of Paul Celan) and enduring themes (tragedy, translation, the inhuman) will surely be cited for many years to come. Yet from the beginning of his career in the late fifties to his last notable works at the turn of the century, he was explicitly engaged in the practice of criticism—the goal of which was to reach the wider republic of readers (not just academicians) with his urgent dispatches on the state of the arts and culture. It was as a critic that he asked to be judged.

IN DRESDEN, a city renowned for the picture-perfect restoration by which it looks the same and yet entirely strange, an old tale of love and deception is playing out.

IN DRESDEN, a city renowned for the picture-perfect restoration by which it looks the same and yet entirely strange, an old tale of love and deception is playing out.

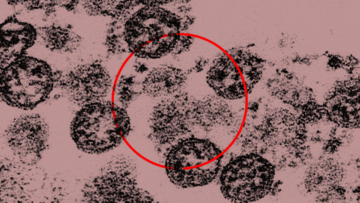

Tiny molecules came up big in 2021. By year’s end, COVID-19 vaccines based on snippets of mRNA, or messenger RNA, proved to be safe and incredibly effective at preventing the worst outcomes of the disease.

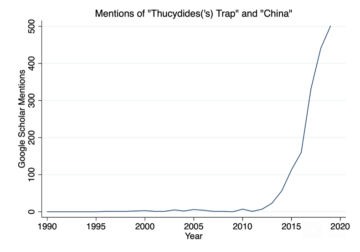

Tiny molecules came up big in 2021. By year’s end, COVID-19 vaccines based on snippets of mRNA, or messenger RNA, proved to be safe and incredibly effective at preventing the worst outcomes of the disease. When I discuss the US-China relationship with people, I’ve found that they often turn to the concept of the “Thucydides Trap.” It seems as if few international relations books in the last decade have had as much influence as

When I discuss the US-China relationship with people, I’ve found that they often turn to the concept of the “Thucydides Trap.” It seems as if few international relations books in the last decade have had as much influence as  William Hasselberger,

William Hasselberger,  IN SEPTEMBER, THE ADMINISTRATION

IN SEPTEMBER, THE ADMINISTRATION  The smooth, plastic egg fits in your palm. Brightly colored shell. Gray screen the size of a postage stamp. Below that, three buttons. Pull a thin plastic tab on the side, and the screen lights up. An 8-bit egg appears onscreen. It quivers and rolls and shakes until, finally, your Tamagotchi is born. Inside your head, the squishy, enigmatic organ known as the brain begins firing — not only to process the visual and sensory stimuli, but to generate curiosity in this new object. In fact, the spark of this fixation likely began before you even held this toy, when you heard friends feverishly speak about it and saw it in the clutches of popular kids at school.

The smooth, plastic egg fits in your palm. Brightly colored shell. Gray screen the size of a postage stamp. Below that, three buttons. Pull a thin plastic tab on the side, and the screen lights up. An 8-bit egg appears onscreen. It quivers and rolls and shakes until, finally, your Tamagotchi is born. Inside your head, the squishy, enigmatic organ known as the brain begins firing — not only to process the visual and sensory stimuli, but to generate curiosity in this new object. In fact, the spark of this fixation likely began before you even held this toy, when you heard friends feverishly speak about it and saw it in the clutches of popular kids at school. In a paper published in Synthese (#53) in 1982, ‘Contemporary Philosophy of Mind’, Richard Rorty wrote an enthusiastic account of the revolutionary ‘Ryle-Dennett tradition’. Was I really as radical a revolutionary as he said I was? I responded mischievously, perhaps rudely:

In a paper published in Synthese (#53) in 1982, ‘Contemporary Philosophy of Mind’, Richard Rorty wrote an enthusiastic account of the revolutionary ‘Ryle-Dennett tradition’. Was I really as radical a revolutionary as he said I was? I responded mischievously, perhaps rudely: My breakthrough infection started with a scratchy throat just a few days before Thanksgiving. Because I’m vaccinated, and had just tested negative for COVID-19 two days earlier, I initially brushed off the symptoms as merely a cold. Just to be sure, I got checked again a few days later. Positive. The result felt like a betrayal after 18 months of reporting on the pandemic. And as I walked home from the testing center, I realized that I had no clue what to do next.

My breakthrough infection started with a scratchy throat just a few days before Thanksgiving. Because I’m vaccinated, and had just tested negative for COVID-19 two days earlier, I initially brushed off the symptoms as merely a cold. Just to be sure, I got checked again a few days later. Positive. The result felt like a betrayal after 18 months of reporting on the pandemic. And as I walked home from the testing center, I realized that I had no clue what to do next. We know by now that authoritarian populists have handled the Covid-19 pandemic badly. Both Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro presided over spiraling death rates, fueled by a disregard for medical science and neglect of public health imperatives.

We know by now that authoritarian populists have handled the Covid-19 pandemic badly. Both Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro presided over spiraling death rates, fueled by a disregard for medical science and neglect of public health imperatives. Harvard Medical School professor of neurology Rudolph Tanzi discusses how lifestyle choices can help maintain brain health during a person’s lifespan. Topics include Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia, the role of genetics and environment in health, and the importance of sleep, exercise, and diet in controlling neuroinflammation.

Harvard Medical School professor of neurology Rudolph Tanzi discusses how lifestyle choices can help maintain brain health during a person’s lifespan. Topics include Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia, the role of genetics and environment in health, and the importance of sleep, exercise, and diet in controlling neuroinflammation. I have a childhood memory of looking in the bathroom mirror, and for the first time realizing that my experience at that precise moment—the experience of being me—would at some point come to an end, and that “I” would die. I must have been about 8 or 9 years old, and like all early memories this one too is unreliable. But perhaps it was at this moment that I also realized that if my consciousness could end, then it must depend in some way on the stuff I was made of—on the physical materiality of my body and my brain. It seems to me that I’ve been grappling with this mystery, in one way or another, ever since.

I have a childhood memory of looking in the bathroom mirror, and for the first time realizing that my experience at that precise moment—the experience of being me—would at some point come to an end, and that “I” would die. I must have been about 8 or 9 years old, and like all early memories this one too is unreliable. But perhaps it was at this moment that I also realized that if my consciousness could end, then it must depend in some way on the stuff I was made of—on the physical materiality of my body and my brain. It seems to me that I’ve been grappling with this mystery, in one way or another, ever since. Only two of the following three cultures are, as far as we know, real. In 2022, perhaps, I will reveal which of them I made up.

Only two of the following three cultures are, as far as we know, real. In 2022, perhaps, I will reveal which of them I made up. The preliminary data about omicron and vaccines is

The preliminary data about omicron and vaccines is  French far-right pundit Éric Zemmour recently launched his presidential campaign with a

French far-right pundit Éric Zemmour recently launched his presidential campaign with a