Jonathan Rowson in aeon:

Arriving at the chess board is like entering an eagerly anticipated party. All my old friends are there: the royal couple, their associates, the reassuringly straight lines of noble infantry. I adjust them, ensuring that they are optimally located in the centre of their starting squares, an anxious fidgeting and tactile caress. I know these pieces, and care about them. They are my responsibility. And I’m grateful to my opponent for obliging me to treat them well on pain of death.

Arriving at the chess board is like entering an eagerly anticipated party. All my old friends are there: the royal couple, their associates, the reassuringly straight lines of noble infantry. I adjust them, ensuring that they are optimally located in the centre of their starting squares, an anxious fidgeting and tactile caress. I know these pieces, and care about them. They are my responsibility. And I’m grateful to my opponent for obliging me to treat them well on pain of death.

In many ways, I owe chess everything. Since the age of five, the game has been a source of friendship, refuge and growth, and I have been a grandmaster for 20 years. The lifelong title is the highest awarded to chess players, and it is based on achieving three qualifying norms in international events that are often peak performances, combined with an international rating reflecting a consistently high level of play – all validated by FIDE, the world chess federation. There are about 1,500 grandmasters in the world. At my peak, I was just outside the world top 100, and I feel some gentle regret at not climbing even higher, but I knew there were limits. Even in the absence of a plan A for my life, chess always felt like plan B, mostly because I couldn’t imagine surrendering myself to competitive ambition. I have not trained or played with serious professional intent for more than a decade, and while my mind remains charmed by the game, my soul feels free of it.

In recent years, I have worked in academic and public policy contexts, attempting to integrate our understanding of complex societal challenges with our inner lives, while also looking after my two sons. I miss many things about not being an active player. I miss the feeling of strength, power and dignity that comes with making good decisions under pressure. I miss the clarity of purpose experienced at each moment of each game, the lucky escapes from defeat, and the thrill of the chase towards victory. But, most of all, I miss the experience of concentration.

More here.

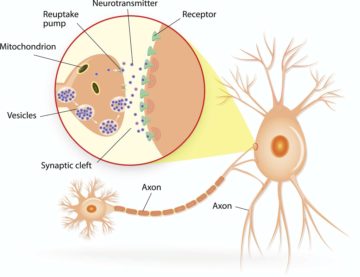

Previously, researchers focused on recording the electrical signals produced by neurons. While these studies have confirmed that neurons change their response to particular stimuli after a memory is formed, they couldn’t pinpoint what drives those changes.

Previously, researchers focused on recording the electrical signals produced by neurons. While these studies have confirmed that neurons change their response to particular stimuli after a memory is formed, they couldn’t pinpoint what drives those changes.

Forster began writing Maurice in 1913, when the British Empire governed nearly a quarter of the earth’s population and the question of nostalgia was beside the point. Forster was thirty-four, eighteen years had passed since

Forster began writing Maurice in 1913, when the British Empire governed nearly a quarter of the earth’s population and the question of nostalgia was beside the point. Forster was thirty-four, eighteen years had passed since  Arriving at the chess board is like entering an eagerly anticipated party. All my old friends are there: the royal couple, their associates, the reassuringly straight lines of noble infantry. I adjust them, ensuring that they are optimally located in the centre of their starting squares, an anxious fidgeting and tactile caress. I know these pieces, and care about them. They are my responsibility. And I’m grateful to my opponent for obliging me to treat them well on pain of death.

Arriving at the chess board is like entering an eagerly anticipated party. All my old friends are there: the royal couple, their associates, the reassuringly straight lines of noble infantry. I adjust them, ensuring that they are optimally located in the centre of their starting squares, an anxious fidgeting and tactile caress. I know these pieces, and care about them. They are my responsibility. And I’m grateful to my opponent for obliging me to treat them well on pain of death. Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World (image: Reprint from the September 1966 issue of AFL-CIO American Federationist, Box 38, Folder 4, William Page Keeton Papers, Special Collections, Tarlton Law Library, The University of Texas at Austin):

Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World (image: Reprint from the September 1966 issue of AFL-CIO American Federationist, Box 38, Folder 4, William Page Keeton Papers, Special Collections, Tarlton Law Library, The University of Texas at Austin): Katie J. M. Baker in Lux:

Katie J. M. Baker in Lux: Roosevelt Montás over at Aeon:

Roosevelt Montás over at Aeon:

I

I The literary scholar Christopher Ricks made a distinction between being “unenchanted” and “disenchanted.” The latter category implies that you have been let down in your hopes and dreams; the former that you never had any to begin with. Didion, of course, belongs to the first breed. Nothing ever seemed to excite her or faze her or disappoint her, largely because she set her sights so low to begin with. She cannot be disabused. Spotting Jim Morrison on a spring evening in 1968 recording a rhythm track leads her to comment on his outfit — “black vinyl pants and no underwear” — and the gnomic remark (one of her specialties) that his whole gestalt suggested “some range of the possible just beyond a suicide pact.” Didion was the archpriestess of cool — possessed of a corrosive sense of irony and an overriding habit of condescension — in a period of greater naïveté and belief than we live in now.

The literary scholar Christopher Ricks made a distinction between being “unenchanted” and “disenchanted.” The latter category implies that you have been let down in your hopes and dreams; the former that you never had any to begin with. Didion, of course, belongs to the first breed. Nothing ever seemed to excite her or faze her or disappoint her, largely because she set her sights so low to begin with. She cannot be disabused. Spotting Jim Morrison on a spring evening in 1968 recording a rhythm track leads her to comment on his outfit — “black vinyl pants and no underwear” — and the gnomic remark (one of her specialties) that his whole gestalt suggested “some range of the possible just beyond a suicide pact.” Didion was the archpriestess of cool — possessed of a corrosive sense of irony and an overriding habit of condescension — in a period of greater naïveté and belief than we live in now. Just after graduating from medical school, Carl Erik Fisher was on top of the world. He was winning awards and working day and night. But a lot of that frantic activity was really covering up his problems with addiction. Fisher – who says he comes from a family with a history of addiction – descended into an alcohol and Adderall binge during residency. A manic episode led to his admission to the Bellevue Hospital Psychiatry ward in New York, where just years ago, he’d interviewed for residency. “Because I was a doctor, because I’m white, because when the NYPD came to get me out of my apartment I was living in an upscale neighborhood —I got a lot of treatment and I got a lot of compassion,” he says. “Sadly, many people with addiction can’t even access services, let alone the kind of quality of services I was able to get.”

Just after graduating from medical school, Carl Erik Fisher was on top of the world. He was winning awards and working day and night. But a lot of that frantic activity was really covering up his problems with addiction. Fisher – who says he comes from a family with a history of addiction – descended into an alcohol and Adderall binge during residency. A manic episode led to his admission to the Bellevue Hospital Psychiatry ward in New York, where just years ago, he’d interviewed for residency. “Because I was a doctor, because I’m white, because when the NYPD came to get me out of my apartment I was living in an upscale neighborhood —I got a lot of treatment and I got a lot of compassion,” he says. “Sadly, many people with addiction can’t even access services, let alone the kind of quality of services I was able to get.” Despite often being lumped together these days in what gratingly gets called the “wellness sector,” psychotherapy and Buddhist meditation might be seen as almost opposite approaches to the search for peace of mind. Show up on the couch of a traditional American shrink, and you’ll be encouraged to delve deep into your personal history and emotional life — to ask how your parents’ anxieties imprinted themselves on your childhood, say, or why the way your spouse loads the dishwasher makes you so disproportionately angry. Show up at a meditation center, by contrast, and you’ll be encouraged to see all those thoughts and emotions as mere passing emotional weather, and the self to which they’re happening as an illusion.

Despite often being lumped together these days in what gratingly gets called the “wellness sector,” psychotherapy and Buddhist meditation might be seen as almost opposite approaches to the search for peace of mind. Show up on the couch of a traditional American shrink, and you’ll be encouraged to delve deep into your personal history and emotional life — to ask how your parents’ anxieties imprinted themselves on your childhood, say, or why the way your spouse loads the dishwasher makes you so disproportionately angry. Show up at a meditation center, by contrast, and you’ll be encouraged to see all those thoughts and emotions as mere passing emotional weather, and the self to which they’re happening as an illusion. Tackiness, it would seem, has always been in the eye of the beholder—a disapproving audience, real or imagined, clicking their proverbial tongues. They usually judge from the other side of some perceived divide, whether cultural, socioeconomic, or generational. “I always thought of tacky as my mother’s word,” Rax King writes at the beginning of her spirited new essay collection .Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer (Vintage, $16). She can still describe with stinging clarity the first time her mother flung the insult at her: she was eight years old, dressed in a puff-painted and bedazzled T-shirt she’d made with a friend so that they’d have something to wear when performing a song-and-dance routine at the elementary school talent show. (The song? An unnamed jig by the ’90s Irish girl group B*Witched, naturally.) “It occurred to me that being tacky was, in some sense, the opposite of being right,” King writes, reconsidering that formative moment two decades later. But even then, beneath the shame triggered by her mother’s laughter, she felt the illicit, hedonistic allure of the tacky: “Why should I put all that work into being right when the alternative was so much more fun?”

Tackiness, it would seem, has always been in the eye of the beholder—a disapproving audience, real or imagined, clicking their proverbial tongues. They usually judge from the other side of some perceived divide, whether cultural, socioeconomic, or generational. “I always thought of tacky as my mother’s word,” Rax King writes at the beginning of her spirited new essay collection .Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer (Vintage, $16). She can still describe with stinging clarity the first time her mother flung the insult at her: she was eight years old, dressed in a puff-painted and bedazzled T-shirt she’d made with a friend so that they’d have something to wear when performing a song-and-dance routine at the elementary school talent show. (The song? An unnamed jig by the ’90s Irish girl group B*Witched, naturally.) “It occurred to me that being tacky was, in some sense, the opposite of being right,” King writes, reconsidering that formative moment two decades later. But even then, beneath the shame triggered by her mother’s laughter, she felt the illicit, hedonistic allure of the tacky: “Why should I put all that work into being right when the alternative was so much more fun?” Last year’s Day of the Dead marked a grim milestone. On 1 November, the global death toll from the COVID-19 pandemic passed 5 million, official data suggested. It has now reached 5.5 million. But that figure is a significant underestimate. Records of excess mortality —

Last year’s Day of the Dead marked a grim milestone. On 1 November, the global death toll from the COVID-19 pandemic passed 5 million, official data suggested. It has now reached 5.5 million. But that figure is a significant underestimate. Records of excess mortality —  I’ve been reading Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s ambitious debut monograph, Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion and Terror 1817–2020. In it, the Pakistani-American scholar ranges over 200 years of history to argue that the West has long used the language of disease centrally in its methods of control.

I’ve been reading Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s ambitious debut monograph, Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion and Terror 1817–2020. In it, the Pakistani-American scholar ranges over 200 years of history to argue that the West has long used the language of disease centrally in its methods of control.