The Freezer Section of the Walmart in the Third Ward

With freezer door open and bags of crinkle cut fries

in my hands, deciphering ingredients my mother

would shun if she read them, I keep losing focus

for the child one aisle over, crying, because her mother

tore from her hands a box of Jolly Rancher Pop Tarts.

(I know this because she screams–Jolly Rancher Pop Tarts.)

I recall brand names of products I never needed—Star Wars

Episode III Anakin figurine with detachable hands

and waist; Nerf Foam Flight Football whose little holes

would whistle when thrown from oily fingers;

the toy I received instead, my favorite, black barbie doll,

whose name I never learned, with a sparkling swimsuit,

appearing on contact with water. My grandmother

gifted her to me, my favorite doll, professional scuba diver

like my mother wished to be. Years later, embarrassed,

I donated her to charity for fear of childishness, for fear

of never finding another with whom to interlock fingers,

drive with windows down, smelling fresh air off fields

in towns with names that we don’t know. Tonight,

outside of Walmart, my car windows rolled down, all I smell

is smoke from the cigarette of the man on the stop light’s curb.

He argues directions with a man not there. Across the street,

behind chained fences, a game of pickup basketball.

Their hoops have no nets, the concrete is cracked,

and players insult, or encourage, one another, with 5’ 1”, air ball,

adopted, until we all return to reality together, hearing

the gunshot echo off the trees and small houses around us,

and I notice the stop light has been blinking red for minutes.

by William Littlejohn-Oram

from Muzzle Magazine, Winter 2021

Here we are, in our ringside seats at a bloody circus, watching on TV and Twitter, trapped between infinite pity and rational self-interest. The tension between two opposing forces is unbearable. Pulling from one side, our horror at a senseless invasion, our wonder at the Ukrainian resistance, the unarmed villagers mobbing a Russian tank or feeding a

Here we are, in our ringside seats at a bloody circus, watching on TV and Twitter, trapped between infinite pity and rational self-interest. The tension between two opposing forces is unbearable. Pulling from one side, our horror at a senseless invasion, our wonder at the Ukrainian resistance, the unarmed villagers mobbing a Russian tank or feeding a  New research, published Feb. 17 in the

New research, published Feb. 17 in the  From 2012 to 2017, I worked as a US air force nuclear missile operator. I was 22 when I started. Each time I descended into the missile silo, I had to be ready to launch, at a moment’s notice, a nuclear weapon that could wipe a city the size of New York off the face of the earth.

From 2012 to 2017, I worked as a US air force nuclear missile operator. I was 22 when I started. Each time I descended into the missile silo, I had to be ready to launch, at a moment’s notice, a nuclear weapon that could wipe a city the size of New York off the face of the earth. WHAT, THOUGH, IF

WHAT, THOUGH, IF THERE IS AN ALMOST CHARMING

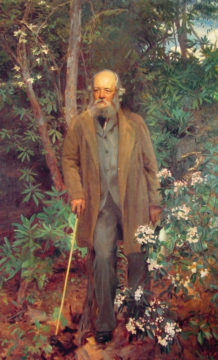

THERE IS AN ALMOST CHARMING What would Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) make of his works today, in the bicentennial year of his birth? No doubt he would be delighted by the survival and continued popularity of so many of his big-city parks, particularly Central Park and Prospect Park, but also parks in Boston, Chicago, and Montreal, as well as Buffalo, Detroit, Rochester, and Louisville. He might be surprised by the bewildering range of activities these parks now accommodate—not only boating and ice-skating, as in his day, but exercising, jogging, picnicking, and games, as well as popular theatrical and musical events. I don’t think this variety would displease him. After all, it was he who introduced free band concerts in Central Park, over the objections of many of his strait-laced colleagues. He would be pleased by the banning of automobiles; his winding carriage drives were never intended for fast—and noisy—traffic.

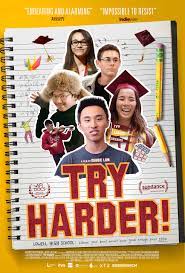

What would Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) make of his works today, in the bicentennial year of his birth? No doubt he would be delighted by the survival and continued popularity of so many of his big-city parks, particularly Central Park and Prospect Park, but also parks in Boston, Chicago, and Montreal, as well as Buffalo, Detroit, Rochester, and Louisville. He might be surprised by the bewildering range of activities these parks now accommodate—not only boating and ice-skating, as in his day, but exercising, jogging, picnicking, and games, as well as popular theatrical and musical events. I don’t think this variety would displease him. After all, it was he who introduced free band concerts in Central Park, over the objections of many of his strait-laced colleagues. He would be pleased by the banning of automobiles; his winding carriage drives were never intended for fast—and noisy—traffic. These anxieties about status are acutely felt among a cohort for whom going to college can seem a foregone conclusion. Asian Americans are often held up as a “model minority,” a group whose presence on campuses like Harvard or M.I.T., where forty per cent of incoming first-years self-identify as Asian American, far outpaces their percentage of the U.S. population. The figure of the model minority emerged in the fifties, a reflection of Cold War-era policies that were designed to attract highly educated immigrants from Asia. Over time, this stereotype ossified. American meritocracy held up the immigrant as proof that its rules were fair, and many high achievers were flattered to play along. Even though many of the gains for Asian Americans could be explained through policy—and even as studies showed how entire swaths of the community were left behind in poverty—the experience of being Asian in America has been rigidly defined by a framework of success and failure. As the scholar erin Khuê Ninh argues in “

These anxieties about status are acutely felt among a cohort for whom going to college can seem a foregone conclusion. Asian Americans are often held up as a “model minority,” a group whose presence on campuses like Harvard or M.I.T., where forty per cent of incoming first-years self-identify as Asian American, far outpaces their percentage of the U.S. population. The figure of the model minority emerged in the fifties, a reflection of Cold War-era policies that were designed to attract highly educated immigrants from Asia. Over time, this stereotype ossified. American meritocracy held up the immigrant as proof that its rules were fair, and many high achievers were flattered to play along. Even though many of the gains for Asian Americans could be explained through policy—and even as studies showed how entire swaths of the community were left behind in poverty—the experience of being Asian in America has been rigidly defined by a framework of success and failure. As the scholar erin Khuê Ninh argues in “ “Those who can, do science,” the economist Paul Samuelson once remarked. “Those who can’t, prattle on about methodology.” Until fairly recently this seemed to be the dominant attitude among mainstream economists, but a sea change came when the global financial system began to unravel in 2007. In the decade and a half since—painful years of sluggish recovery, stagnating real wages, yawning inequality, and populist upheaval—reflexive talk has exploded. Why was the crash not widely predicted? Was the “efficient market hypothesis” to blame? Have lessons from the Great Depression been forgotten? And why are core questions about finance, power, inequality, and capitalism still largely missing from Economics 101?

“Those who can, do science,” the economist Paul Samuelson once remarked. “Those who can’t, prattle on about methodology.” Until fairly recently this seemed to be the dominant attitude among mainstream economists, but a sea change came when the global financial system began to unravel in 2007. In the decade and a half since—painful years of sluggish recovery, stagnating real wages, yawning inequality, and populist upheaval—reflexive talk has exploded. Why was the crash not widely predicted? Was the “efficient market hypothesis” to blame? Have lessons from the Great Depression been forgotten? And why are core questions about finance, power, inequality, and capitalism still largely missing from Economics 101? The united states

The united states “Why is Ukraine the West’s fault?” This is the provocative title of a talk by Professor John Mearsheimer – a famous exponent of international relations (IR) realism – given at an alumni gathering of the University of Chicago in 2015. Since it was first posted on

“Why is Ukraine the West’s fault?” This is the provocative title of a talk by Professor John Mearsheimer – a famous exponent of international relations (IR) realism – given at an alumni gathering of the University of Chicago in 2015. Since it was first posted on  “Does Anyone Have the Right to Sex?” was a shrewd yet compassionate essay, marked by rigorous thinking as well as the hope that we might make room for desires that don’t follow patriarchy’s scripts, without blaming people for desiring what they’ve been told to want. Srinivasan gestured in the essay toward a new feminist perspective, one that would draw on the work of the second-wave feminists of the 1960s and ’70s, who took questions of sexual desire seriously, without replicating some of their blind spots concerning race and class. Such a perspective would also preserve aspects of more recent feminist thinking—an emphasis on individual freedom, an awareness of the ways different forms of oppression intersect—without suggesting that desire is inherently good or just. Her aim was not to legislate anyone’s desires—that would be authoritarian—but rather to encourage readers to question their sexual preferences, to see their own desires as a starting point for inquiry rather than its end. There is no right to sex, she wrote, but there may be “a duty to transfigure, as best we can, our desires” so that they better align with our political goals

“Does Anyone Have the Right to Sex?” was a shrewd yet compassionate essay, marked by rigorous thinking as well as the hope that we might make room for desires that don’t follow patriarchy’s scripts, without blaming people for desiring what they’ve been told to want. Srinivasan gestured in the essay toward a new feminist perspective, one that would draw on the work of the second-wave feminists of the 1960s and ’70s, who took questions of sexual desire seriously, without replicating some of their blind spots concerning race and class. Such a perspective would also preserve aspects of more recent feminist thinking—an emphasis on individual freedom, an awareness of the ways different forms of oppression intersect—without suggesting that desire is inherently good or just. Her aim was not to legislate anyone’s desires—that would be authoritarian—but rather to encourage readers to question their sexual preferences, to see their own desires as a starting point for inquiry rather than its end. There is no right to sex, she wrote, but there may be “a duty to transfigure, as best we can, our desires” so that they better align with our political goals Understanding this complex tangle of overlapping titles and jurisdictions is here essential. For although Maria Theresa was sovereign in her own right of the archduchy of Austria and queen of Hungary, in legal theory she ranked lower than her husband, the newly elected emperor. Yet having regained her realms as a woman against one set of male rivals, Maria Theresa was determined not to cede authority to another set closer to home. She insisted that her power within her inherited possessions was absolute. Stollberg-Rilinger argues that even within the Holy Roman Empire, nominally her husband’s domain, it was Maria Theresa, not the emperor, who decided the direction of policy. This female primacy would be continued, with even sharper resentment on the part of the subordinated male, after Francis’s death in 1765 and the election of her eldest son, Joseph II, as his successor as Holy Roman Emperor.

Understanding this complex tangle of overlapping titles and jurisdictions is here essential. For although Maria Theresa was sovereign in her own right of the archduchy of Austria and queen of Hungary, in legal theory she ranked lower than her husband, the newly elected emperor. Yet having regained her realms as a woman against one set of male rivals, Maria Theresa was determined not to cede authority to another set closer to home. She insisted that her power within her inherited possessions was absolute. Stollberg-Rilinger argues that even within the Holy Roman Empire, nominally her husband’s domain, it was Maria Theresa, not the emperor, who decided the direction of policy. This female primacy would be continued, with even sharper resentment on the part of the subordinated male, after Francis’s death in 1765 and the election of her eldest son, Joseph II, as his successor as Holy Roman Emperor. THE HARVARD

THE HARVARD When guests used to visit Vladimir Putin in his office in the Kremlin’s Senate Palace, he’d point at the bookshelves and ask them to choose a book from Joseph Stalin’s library. Half of Stalin’s books – usually marked up by the Soviet leader himself with red or green crayons – remain in Putin’s office. As one of his ministers told me, Putin would ask the visitor to open the book and they would look together at whatever marginalia Stalin had written: sometimes it was a grim laugh: “xa-xa-xa!”; sometimes a snort of disdain: “green steam!”; at others it was just a word: “teacher” was written on the biography of Ivan the Terrible.

When guests used to visit Vladimir Putin in his office in the Kremlin’s Senate Palace, he’d point at the bookshelves and ask them to choose a book from Joseph Stalin’s library. Half of Stalin’s books – usually marked up by the Soviet leader himself with red or green crayons – remain in Putin’s office. As one of his ministers told me, Putin would ask the visitor to open the book and they would look together at whatever marginalia Stalin had written: sometimes it was a grim laugh: “xa-xa-xa!”; sometimes a snort of disdain: “green steam!”; at others it was just a word: “teacher” was written on the biography of Ivan the Terrible.