Category: Archives

NATO and the Road Not Taken

Rajan Menon in the Boston Review:

After a prolonged buildup of forces, the total reaching 120,000 soldiers and National Guard troops, Russian President Vladimir Putin decided on February 24 to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The decision has revived a sharp-elbowed debate in the United States. One side consists mainly, though not exclusively, of those belonging to the realist school of thought. This side insists that Putin’s move can only be understood by taking account of the friction that NATO’s eastward expansion created between Russia and the United States. The other side, primarily comprised of neoconservatives and liberal internationalists, retorts that Putin’s protests against NATO’s enlargement are bogus. They contend that Putin’s animosity toward democracy—particularly the fear that its success in Ukraine would rub off on Russia and bring down the state that he has built since 2000—was the sole reason for the war.

After a prolonged buildup of forces, the total reaching 120,000 soldiers and National Guard troops, Russian President Vladimir Putin decided on February 24 to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The decision has revived a sharp-elbowed debate in the United States. One side consists mainly, though not exclusively, of those belonging to the realist school of thought. This side insists that Putin’s move can only be understood by taking account of the friction that NATO’s eastward expansion created between Russia and the United States. The other side, primarily comprised of neoconservatives and liberal internationalists, retorts that Putin’s protests against NATO’s enlargement are bogus. They contend that Putin’s animosity toward democracy—particularly the fear that its success in Ukraine would rub off on Russia and bring down the state that he has built since 2000—was the sole reason for the war.

Both sides have succumbed to the single factor fallacy. Given the complexities of history and politics, why should we assume that Putin has only one aim, only one apprehension? In consequence their exchanges have been inconclusive, producing more heat than light.

More here.

Wednesday, March 16, 2022

Slavoj Žižek – DVD Picks

The Gita According to Marcus Aurelius

Amit Majmudar at The Marginalia Review:

In his litany of beautiful things, Marcus Aurelius mentions a sword in the same breath as a blossom.

In his litany of beautiful things, Marcus Aurelius mentions a sword in the same breath as a blossom.

“Among the Quadi, on the river Gran” is the only reference to the barbarian tribes that Marcus Aurelius fought. Nowhere do we find assertions that the barbarians are despicable and deserve to have their way of life destroyed. There are no rants against the Quadi, no lurid accounts of Quadi evil that justify their subjugation. Marcus fought the Quadi without demonizing them.

The Mahabharata war centered on two rival sets of cousins, the five Pandavas and the hundred Kauravas. Arjuna is a Pandava, and Krishna is his mentor. After vowing not to take up arms in the war, Krishna serves as Arjuna’s charioteer. In the Gita, Krishna never launches into a tirade against the Kauravas. He never says a word against them. “Infidels,” “pagans,” “heathen,” “savages”: The Gita is missing these words. It is a rare scripture without an outgroup. Arjuna fought the Kauravas without demonizing them.

more here.

The Peter Handke Controversy

Ruth Franklin at The New Yorker:

On December 10, 2019, the Austrian writer Peter Handke received the Nobel Prize in Literature. If he felt pride or triumph, he didn’t show it. His bow tie askance above an ill-fitting white dress shirt, his eyes unsmiling behind his trademark round glasses, Handke looked resigned and stoical, as if he were submitting to a bothersome medical procedure. As he accepted his award, some of the onlookers—not all of whom joined in the applause—appeared equally grim.

On December 10, 2019, the Austrian writer Peter Handke received the Nobel Prize in Literature. If he felt pride or triumph, he didn’t show it. His bow tie askance above an ill-fitting white dress shirt, his eyes unsmiling behind his trademark round glasses, Handke looked resigned and stoical, as if he were submitting to a bothersome medical procedure. As he accepted his award, some of the onlookers—not all of whom joined in the applause—appeared equally grim.

Handke embarked on his career, in the nineteen-sixties, as a provocateur, with absurdist theatrical works that eschewed action, character, and dialogue for, in the words of one critic, “anonymous, threatening rants.” One of his early plays, titled “Offending the Audience,” ends with the actors hurling insults at the spectators.

more here.

No One Is Talking About This v. Several People Are Typing

Kasulke and Lockwood in The Morning News:

I’m uncomfortable saying a book that was a Good Morning America Book Club pick is underhyped. But Calvin Kasulke’s Several People Are Typing should get more recognition for how truly ambitious this book is. It’s set up as only being inside Slack and has to follow all the maddening logic of Slack, from side groups to bots, to the infuriating languages and social cultures that offices make for themselves.

I’m uncomfortable saying a book that was a Good Morning America Book Club pick is underhyped. But Calvin Kasulke’s Several People Are Typing should get more recognition for how truly ambitious this book is. It’s set up as only being inside Slack and has to follow all the maddening logic of Slack, from side groups to bots, to the infuriating languages and social cultures that offices make for themselves.

This book has to do several things that readers expect novels to do (characters, ideas, plot, setting, worldbuilding) while balancing an understanding of Slack and potential readers’ understanding of that software designed to ostensibly be a place of business communications and workflow. The first half of this novel was maybe the most exciting book I read last year because it takes an absurd premise while navigating all those craft elements: As Gerald No-Last-Name-Given awoke from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed into a sentient Slackbot. The rest of his colleagues think he is doing a bit until one of them finally agrees to check in on him. “I’m going to treat this like cat sitting, okay?” a character decides after seeing Gerald’s “Slack-Coma.” The rest of the office is obsessed with their work, their romances, and all the petty dehumanizing tasks of a modern American office place. Things continue to escalate on Gerald’s end, but for many of the workers involved in the novel, their plots move around the petty intrigues of the office: who gets a prime desk location, who is perceived as “productive,” and covering up a workplace romance.

More here.

How Much Medieval Literature Has Been Lost?

Sophie Bushwick in Scientific American:

How is a lost tale of chivalry from medieval Europe like an unknown species of animal? According to a new study, the number of both items can be tallied using exactly the same mathematical model. The findings align with existing estimates of lost literature—and suggest that ecological models can be applied to a surprising variety of social science fields.

How is a lost tale of chivalry from medieval Europe like an unknown species of animal? According to a new study, the number of both items can be tallied using exactly the same mathematical model. The findings align with existing estimates of lost literature—and suggest that ecological models can be applied to a surprising variety of social science fields.

Experts know that much fiction from the medieval era (roughly from the beginning of the fifth century A.D. to the end of the 14th century), such as chivalric romances about King Arthur’s court, has disappeared over time. But quantifying that loss is difficult. “One thing we don’t know is … the portion of literature that didn’t survive,” says the new study’s co-author Mike Kestemont, an associate professor in the department of literature at the University of Antwerp in Belgium. Learning about what was lost can teach scholars more about the medieval period, and there are also present-day reasons to value this work, adds co-author Daniel Sawyer, a research fellow in medieval English literature at the University of Oxford. “Thinking about how cultural heritage survives seems like a useful thing to do, because right now—among many other things—that’s one of the important things threatened by things like climate change,” Sawyer says. “In the longer run, we as a species probably need to be thinking about ‘How do we preserve and record what we have?’ And knowing more about what kind of patterns of distribution can help survival of these things is not irrelevant to that.”

More here.

How Millions of Lives Might Have Been Saved From Covid-19

Zeynep Tufekci in the New York Times:

What if China had been open and honest in December 2019? What if the world had reacted as quickly and aggressively in January 2020 as Taiwan did? What if the United States had put appropriate protective measures in place in February 2020, as South Korea did?

What if China had been open and honest in December 2019? What if the world had reacted as quickly and aggressively in January 2020 as Taiwan did? What if the United States had put appropriate protective measures in place in February 2020, as South Korea did?

To examine these questions is to uncover a brutal truth: Much suffering was avoidable, again and again, if different choices that were available and plausible had been made at crucial turning points. By looking at them, and understanding what went wrong, we can hope to avoid similar mistakes in the future.

More here.

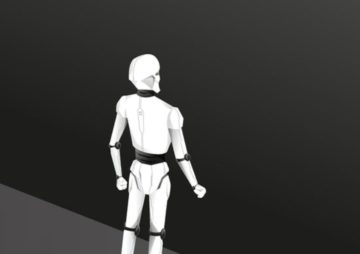

Gary Markus: Deep Learning Is Hitting a Wall

Gary Markus in Nautilus:

Let me start by saying a few things that seem obvious,” Geoffrey Hinton, “Godfather” of deep learning, and one of the most celebrated scientists of our time, told a leading AI conference in Toronto in 2016. “If you work as a radiologist you’re like the coyote that’s already over the edge of the cliff but hasn’t looked down.” Deep learning is so well-suited to reading images from MRIs and CT scans, he reasoned, that people should “stop training radiologists now” and that it’s “just completely obvious within five years deep learning is going to do better.”

Let me start by saying a few things that seem obvious,” Geoffrey Hinton, “Godfather” of deep learning, and one of the most celebrated scientists of our time, told a leading AI conference in Toronto in 2016. “If you work as a radiologist you’re like the coyote that’s already over the edge of the cliff but hasn’t looked down.” Deep learning is so well-suited to reading images from MRIs and CT scans, he reasoned, that people should “stop training radiologists now” and that it’s “just completely obvious within five years deep learning is going to do better.”

Fast forward to 2022, and not a single radiologist has been replaced. Rather, the consensus view nowadays is that machine learning for radiology is harder than it looks; at least for now, humans and machines complement each other’s strengths.

Few fields have been more filled with hype and bravado than artificial intelligence. It has flitted from fad to fad decade by decade, always promising the moon, and only occasionally delivering. One minute it was expert systems, next it was Bayesian networks, and then Support Vector Machines. In 2011, it was IBM’s Watson, once pitched as a revolution in medicine, more recently sold for parts.

More here.

George Lakoff: Is Mathematics Invented or Discovered?

What would be signs protests in Russia are making a difference?

Christina Pazzanese in The Harvard Gazette:

A protest movement against the invasion of Ukraine is growing in Russia. Demonstrations were held in 60 cities on March 6 and in 37 on Sunday, spurred in part by calls to turn out from imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny. More than 14,900 people have been detained by security forces and police for protesting, according to OVD-Info, a Russian human rights organization.

A protest movement against the invasion of Ukraine is growing in Russia. Demonstrations were held in 60 cities on March 6 and in 37 on Sunday, spurred in part by calls to turn out from imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny. More than 14,900 people have been detained by security forces and police for protesting, according to OVD-Info, a Russian human rights organization.

To quell dissent, Russia has intensified a crackdown on independent Russian news outlets, cut off access to social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, and declared spreading “false information” about the war a criminal offense punishable by up to 15 years in jail. The moves effectively left state-run media outlets as the only sources permitted to report on the attack and the protests without fear of reprisal.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

The Stranger

A man came up to me as I was walking home from the pharmacy: “Are you Jose Hernandez Diaz?” “Yes,” I said, “who’s asking?” “Do you enjoy sipping tea before bedtime?” “Well, I do, but what is it to you?” I asked. “In the ninth grade, did you get cut from the basketball team?” “I did, in fact, get cut from the team.” “Do you sometimes wonder what life would’ve been like had you married Margot Cisneros?” “Maybe, sometimes, yes,” I said. “Are you afraid of small talk and long walks in the city?” “I’m just a little introverted,” I said. “Does the night sky resemble a dragon of your dreams?” “Yes, thank you for asking,” I said. “Did you cry when Muncy hit that home run in the World Series?” “I did cry at that moment. Proud of it!” “Were you born and raised back and forth between L.A. and Orange County?” “Story of my life; yes,” I said. “Does the night sky resemble a dragon of your dreams?” “Yes, thank you for asking. Yes!”

by Jose Hernandez Diaz

from the Yale Poetry Review, 3/9/22

Tuesday, March 15, 2022

The Stormy Daniels You Haven’t Heard Before: the adult film doyenne on porn, feminism, and identity

Alexis Grenell in The Nation:

Like much of the world, I’ve been captivated by adult film actress turned director Stormy Daniels—but not for the usual reasons. Her encounter with former President Donald Trump is the least interesting thing about this otherwise brilliant, original, and deeply fascinating person whose single-minded pursuit to defend her dignity is mostly lost amid a rage of salacious headlines.

Like much of the world, I’ve been captivated by adult film actress turned director Stormy Daniels—but not for the usual reasons. Her encounter with former President Donald Trump is the least interesting thing about this otherwise brilliant, original, and deeply fascinating person whose single-minded pursuit to defend her dignity is mostly lost amid a rage of salacious headlines.

Daniels complicates the narrative about who is afforded rights and respect. She makes no apologies for who she is, while demanding her place in the public forum as an honest and decent person. She’s also unbelievably witty, and like Mae West before her, exposes the hypocrisy of our laws and mores by landing perfect one-liners on her critics.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Arik Kershenbaum on What Aliens Will Be Like

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

If extraterrestrial life is out there — not just microbial slime, but big, complex, macroscopic organisms — what will they be like? Movies have trained us to think that they won’t be that different at all; they’ll even drink and play music at the same cafes that humans frequent. A bit of imagination, however, makes us wonder whether they won’t be completely alien — we have zero data about what extraterrestrial biology could be like, so it makes sense to keep an open mind. Arik Kershenbaum argues for a judicious middle ground. He points to constraints from physics and chemistry, as well as the tendency of evolution to converge toward successful designs, as reasons to think that biologically complex aliens won’t be utterly different from us after all.

If extraterrestrial life is out there — not just microbial slime, but big, complex, macroscopic organisms — what will they be like? Movies have trained us to think that they won’t be that different at all; they’ll even drink and play music at the same cafes that humans frequent. A bit of imagination, however, makes us wonder whether they won’t be completely alien — we have zero data about what extraterrestrial biology could be like, so it makes sense to keep an open mind. Arik Kershenbaum argues for a judicious middle ground. He points to constraints from physics and chemistry, as well as the tendency of evolution to converge toward successful designs, as reasons to think that biologically complex aliens won’t be utterly different from us after all.

More here.

Ian Bremmer: What the War in Ukraine Means for the World Order

Possible Outcomes of the Russo-Ukrainian War and China’s Choice

Hu Wei in U.S.-China Perception Monitor:

The Russo-Ukrainian War is the most severe geopolitical conflict since World War II and will result in far greater global consequences than September 11 attacks. At this critical moment, China needs to accurately analyze and assess the direction of the war and its potential impact on the international landscape. At the same time, in order to strive for a relatively favorable external environment, China needs to respond flexibly and make strategic choices that conform to its long-term interests.

The Russo-Ukrainian War is the most severe geopolitical conflict since World War II and will result in far greater global consequences than September 11 attacks. At this critical moment, China needs to accurately analyze and assess the direction of the war and its potential impact on the international landscape. At the same time, in order to strive for a relatively favorable external environment, China needs to respond flexibly and make strategic choices that conform to its long-term interests.

Russia’s ‘special military operation’ against Ukraine has caused great controvsery in China, with its supporters and opponents being divided into two implacably opposing sides. This article does not represent any party and, for the judgment and reference of the highest decision-making level in China, this article conducts an objective analysis on the possible war consequences along with their corresponding countermeasure options.

More here.

In Our Time: Peter Kropotkin

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nmq3Tn2l0bk&ab_channel=InOurTime

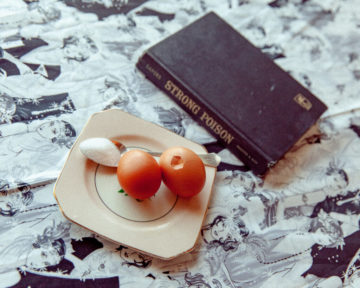

Cooking With Dorothy Sayers

Valerie Stivers at The Paris Review:

Dorothy Sayers’s Strong Poison opens with a description of a man’s last meal before death. The deceased, Philip Boyes, was a writer with “advanced” ideas, dining at the home of his wealthy great-nephew, Norman Urquhart, a lawyer. A judge tells a jury what he ate: the meal starts with a glass of 1847 oloroso “by way of cocktail,” followed by a cup of cold bouillon—“very strong, good soup, set to a clear jelly”—then turbot with sauce, poulet en casserole, and finally a sweet omelet stuffed with jam and prepared tableside. The point of the description is to show that Boyes couldn’t have been poisoned, since every dish was shared, with the exception of a bottle of Burgundy (Corton), which he drank alone. The judge’s oration is another strike against the accused, a bohemian mystery novelist named Harriet Vane, who saw Boyes on the night he died, and had both motive and opportunity to poison him. Looking on from the audience, the famous amateur detective Lord Peter Wimsey writhes in misery; he believes Harriet Vane is innocent, and he has fallen suddenly and completely in love with her.

Dorothy Sayers’s Strong Poison opens with a description of a man’s last meal before death. The deceased, Philip Boyes, was a writer with “advanced” ideas, dining at the home of his wealthy great-nephew, Norman Urquhart, a lawyer. A judge tells a jury what he ate: the meal starts with a glass of 1847 oloroso “by way of cocktail,” followed by a cup of cold bouillon—“very strong, good soup, set to a clear jelly”—then turbot with sauce, poulet en casserole, and finally a sweet omelet stuffed with jam and prepared tableside. The point of the description is to show that Boyes couldn’t have been poisoned, since every dish was shared, with the exception of a bottle of Burgundy (Corton), which he drank alone. The judge’s oration is another strike against the accused, a bohemian mystery novelist named Harriet Vane, who saw Boyes on the night he died, and had both motive and opportunity to poison him. Looking on from the audience, the famous amateur detective Lord Peter Wimsey writhes in misery; he believes Harriet Vane is innocent, and he has fallen suddenly and completely in love with her.

more here.

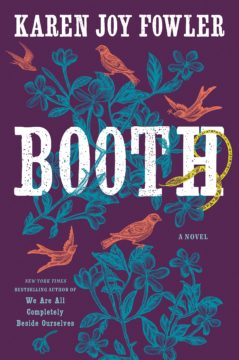

Booth By Karen Joy Fowler

Clare Clark at Literary Review:

On 14 April 1865, less than a week after Confederate General Robert E Lee surrendered his army in Virginia and effectively ended the American Civil War, John Wilkes Booth gained entry to the private box at the theatre in Washington, DC, where Abraham Lincoln and his guests were watching a performance of Our American Cousin and shot the president in the head. Lincoln was pronounced dead the next morning. His assassination thrust much of the country into fresh despair and prompted the largest manhunt in American history.

On 14 April 1865, less than a week after Confederate General Robert E Lee surrendered his army in Virginia and effectively ended the American Civil War, John Wilkes Booth gained entry to the private box at the theatre in Washington, DC, where Abraham Lincoln and his guests were watching a performance of Our American Cousin and shot the president in the head. Lincoln was pronounced dead the next morning. His assassination thrust much of the country into fresh despair and prompted the largest manhunt in American history.

Booth is Karen Joy Fowler’s ambitious exploration of the family at the centre of this seismic moment in the making of modern America – the entire family, that is, except John Wilkes Booth himself. In an author’s note at the end of the novel, Fowler acknowledges that it was never her intention to write a book about John Wilkes (known to the family as Johnny). He was, she writes, ‘a man who craved attention and has gotten too much of it; I didn’t think he deserved mine.’

more here.

Tuesday Poem

“So much to write, so little light.”

……………………. —Tmavý Svetlý

The Origin of Light

For a thousand years, the nature of light

was a source of debate, a question

that split the learned, who wondered if sight

originated as a beam coming in

from outside-the sun-or as a substance

generated inside, a stuff we shoot

out, to bathe the world and its occupants?

Curious. I never knew of this dispute

until a patient, about week before he died

of cancer, told me the story of Ali

al-Hasan, the curious man who tried

staring into the sun for as long as he

could take it. When the pain became too sharp

to stand, he understood, but it was dark

by Jack Coulehan

from Rattle #16, Winter 2001