Category: Archives

Thursday Poem

The Moon is Trans

The moon is trans.

From this moment forward, the moon is trans.

You don’t get to write about the moon anymore unless you respect that.

You don’t get to talk to the moon anymore unless you use her correct pronouns.

You don’t get to send men to the moon anymore unless their job is

to bow down before her and apologize for the sins of the earth.

She is waiting for you, pulling at you softly,

telling you to shut the fuck up already please.

Scientists theorize the moon was once a part of the earth

that broke off when another planet struck it.

Eve came from Adam’s rib.

Etc.

Do you believe in the power of not listening

to the inside of your own head?

I believe in the power of you not listening

to the inside of your own head.

This is all upside down.

We should be talking about the ways that blood

is similar to the part of outer space between the earth and the moon

but we’re busy drawing it instead.

The moon is often described as dead, though she is very much alive.

The moon has not known the feeling of not wanting to be dead

for any extended period of time

in all of her existence, but

she is not delicate and she is not weak.

She is constantly moving away from you the only way she can.

She never turns her face from you because of what you might do.

She will outlive everything you know.

by Joshua Jennifer Espinoza

from Read Good Poetry

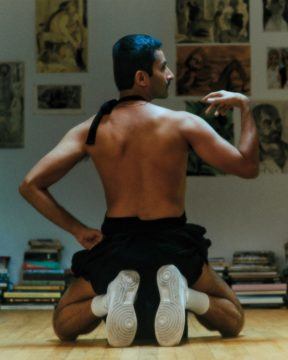

How Salman Toor Left the Old Masters Behind

Calvin Tomkins in The New Yorker:

Three weeks before Salman Toor’s “No Ordinary Love” opened at the Baltimore Museum of Art, on May 22nd, the twenty-six paintings in the exhibition were still in his Brooklyn studio, and the largest work, “Fag Puddle with Candle, Shoe and Flag,” rested against a pillar near the center of the room. Ninety-three inches high by ninety inches wide, it is the same size, Toor told me, as Anthony van Dyck’s “Rinaldo and Armida,” a Baroque painting that is in the museum’s permanent collection. Toor had been obsessed with this picture when he was an art student. He had painted “Fag Puddle” with the idea that it would be “in conversation” with “Rinaldo and Armida,” and, while his show is on view elsewhere at the museum, the two paintings will be facing each other on opposite walls of the same Old Master gallery.

Three weeks before Salman Toor’s “No Ordinary Love” opened at the Baltimore Museum of Art, on May 22nd, the twenty-six paintings in the exhibition were still in his Brooklyn studio, and the largest work, “Fag Puddle with Candle, Shoe and Flag,” rested against a pillar near the center of the room. Ninety-three inches high by ninety inches wide, it is the same size, Toor told me, as Anthony van Dyck’s “Rinaldo and Armida,” a Baroque painting that is in the museum’s permanent collection. Toor had been obsessed with this picture when he was an art student. He had painted “Fag Puddle” with the idea that it would be “in conversation” with “Rinaldo and Armida,” and, while his show is on view elsewhere at the museum, the two paintings will be facing each other on opposite walls of the same Old Master gallery.

“ ‘Rinaldo and Armida’ is based on a poem by Tasso, about the adventures of Christian soldiers in the Crusades,” Toor explained. It was typical of the Baroque, he added, full of bodies and tumult and weather conditions—“a storm coming, the sunset, a mermaid, and the spellbound kiss that’s about to happen between the sleeping soldier and Armida, an enchantress descending to seduce this guy and take him to an island of love where he’ll forget his duties as a crusader.” Toor’s painting, as he describes it, is “a pile of laundry filled with things from different parts of my imagination, things that, to me, sum up an exhaustive heap of greed and lust. I also wanted it to have a slightly dark humor.” “Fag Puddle” is predominantly green, with vivid details in yellow and red. Figurative but not realistic, it shows, in addition to the items in the title, a feather boa, an open book, a dildo, a disembodied foot, a head with a clown nose, a striped necktie, a hanging light bulb, a pearl necklace, a light-emitting iPhone on a tripod, and a man’s head face down in the groin of a nude, upside-down male figure. These unrelated images are painted with such panache and fluency that they seem to belong together. My immediate reaction was that this artist could paint anything and make me believe in it.

Toor is a newcomer to art-world stardom. Slim, dark-haired, and thirty-nine years old, he has a quiet self-confidence that puts him at ease with most people. He was born in Lahore, Pakistan, but he has lived mainly in New York since he graduated from the Pratt Institute, in 2009.

More here.

Female monkeys with female friends live longer

Elizabeth Kivowitz in Phys.Org:

Female white-faced capuchin monkeys living in the tropical dry forests of northwestern Costa Rica may have figured out the secret to a longer life—having fellow females as friends. “As humans, we assume there is some benefit to social interactions, but it is really hard to measure the success of our behavioral strategies,” said UCLA anthropology professor and field primatologist Susan Perry. “Why do we invest so much in our relationships with others? Does it lead to a longer lifespan? Does it lead to more reproductive success? It requires a colossal effort to measure this in humans and other animals.”

Female white-faced capuchin monkeys living in the tropical dry forests of northwestern Costa Rica may have figured out the secret to a longer life—having fellow females as friends. “As humans, we assume there is some benefit to social interactions, but it is really hard to measure the success of our behavioral strategies,” said UCLA anthropology professor and field primatologist Susan Perry. “Why do we invest so much in our relationships with others? Does it lead to a longer lifespan? Does it lead to more reproductive success? It requires a colossal effort to measure this in humans and other animals.”

Perry would know. Since 1990, she has been directing Lomas Barbudal Capuchin Monkey Project in Guanacaste, Costa Rica, where her team of researchers document the daily life of hundreds of large-brained monkeys. While chimpanzees and orangutans are more closely related to humans, the white-faced capuchin monkey has highly sophisticated social structures that influence behavior and are passed to others.

Throughout the year, Perry’s team of graduate students, postdoctoral students, international volunteers and local researchers, trek into the forest for 13-hour days of observation to try to draw conclusions that may help us understand our own relationships, culture and other behaviors.

More here.

Wednesday, August 10, 2022

In Our Time: Angkor Wat

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tx-O2EvlP7Y&ab_channel=InOurTime

The Measuring Muse

Peter Filkins at Salmagundi:

The role of poet-critics is a special one in any literature. Practitioners of the art, they also reveal its underpinnings, an activity that involves more than a mere thumbs-up-or-down review. Instead, by shaping whom and how we read, their influence can be considerable. Randall Jarrell famously dissected poets in regards to their best, or most often, worst tendencies. T.S. Eliot, on the other hand, took the high road, gazing calmly over the centuries while situating poets amid a cultural landscape over which he sought to reign. Usually, however, the stakes are not that high, for most often the role of the poet-critic is neither to delineate nor disseminate, but rather to illuminate. In such manner the main subject of the poet-critic, versus that of the literary critic or reviewer, is poetry itself. Reviewers tell us what a book of poems is “about”; the poet-critic reminds us of what poetry is and can be.

The role of poet-critics is a special one in any literature. Practitioners of the art, they also reveal its underpinnings, an activity that involves more than a mere thumbs-up-or-down review. Instead, by shaping whom and how we read, their influence can be considerable. Randall Jarrell famously dissected poets in regards to their best, or most often, worst tendencies. T.S. Eliot, on the other hand, took the high road, gazing calmly over the centuries while situating poets amid a cultural landscape over which he sought to reign. Usually, however, the stakes are not that high, for most often the role of the poet-critic is neither to delineate nor disseminate, but rather to illuminate. In such manner the main subject of the poet-critic, versus that of the literary critic or reviewer, is poetry itself. Reviewers tell us what a book of poems is “about”; the poet-critic reminds us of what poetry is and can be.

more here.

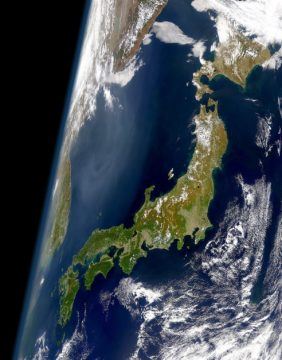

Letter from Japan

Charles De Wolf at Commonweal:

Still, national images are always subject to fluctuation, and at least in the West, historical shifts in the perception of Japan have been particularly dramatic. A much darker view of the country—as a land of ferocious militarists caught up in a death cult—was already fading when I was a boy in the early postwar years. U.S. soldiers returning from Japan showed color slides of Kyoto temples and stately young women in kimonos. Soon Japan was being described as the proverbial phoenix rising from the ashes, now firmly committed to democracy and staunchly allied with its former enemy, the United States. Growing interest in Japan and Japanese culture, particularly in the late 1970s and early 1980s, led to an exaggerated picture of the nation’s strength. Admiration was mixed with misplaced envy, with “Japan Incorporated” now perceived as a new kind of Imperial Japan, with black-suited businessmen replacing sword-wielding warriors. Teaching Japanese and linguistics in a liberal-arts college in upstate New York for two years in the late 1980s, I met students eager to live in Japan long enough to master the language, obtain MBAs from a prestigious American institution, and thereby make their fortunes. Then in the early 1990s, the economic bubble burst. The rising superpower was now suddenly being described with another cliché—the land of the setting sun.

Still, national images are always subject to fluctuation, and at least in the West, historical shifts in the perception of Japan have been particularly dramatic. A much darker view of the country—as a land of ferocious militarists caught up in a death cult—was already fading when I was a boy in the early postwar years. U.S. soldiers returning from Japan showed color slides of Kyoto temples and stately young women in kimonos. Soon Japan was being described as the proverbial phoenix rising from the ashes, now firmly committed to democracy and staunchly allied with its former enemy, the United States. Growing interest in Japan and Japanese culture, particularly in the late 1970s and early 1980s, led to an exaggerated picture of the nation’s strength. Admiration was mixed with misplaced envy, with “Japan Incorporated” now perceived as a new kind of Imperial Japan, with black-suited businessmen replacing sword-wielding warriors. Teaching Japanese and linguistics in a liberal-arts college in upstate New York for two years in the late 1980s, I met students eager to live in Japan long enough to master the language, obtain MBAs from a prestigious American institution, and thereby make their fortunes. Then in the early 1990s, the economic bubble burst. The rising superpower was now suddenly being described with another cliché—the land of the setting sun.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Sun To God

The children walked.

Then they began to run.

Why are we running, one asked?

No one knew. They ran faster.

They began laughing.

Why are we laughing?

Not one knew. They laughed more.

It was the eve of war but they didn’t know.

The children walked.

The children’s parents walked.

The parents’ parents walked.

Their shadows spilled ahead.

Their shadows lagged behind.

Then, they began to run.

No one was laughing

by Ladan Osman

from The Rumpus,

On the Life and Work of Buckminster Fuller

Pradeep Niroula in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

It just so happens Fuller’s popular legacy is bloated, like the geodesic domes he is most easily identified with today. Alec Nevala-Lee’s new biography, Inventor of the Future, fact-checks Fuller’s legend and then corrects the record. Nevala-Lee himself discovered Fuller through the pages of the counterculture bible, Whole Earth Catalog, and grew up admiring him. But, in writing Fuller’s biography, he resists the hypnotic whirlpool surrounding Fuller. Known to be an unreliable narrator of his own life, Fuller inflated numbers, misrepresented facts, and invented stories of epiphanies and revelations. The legends and myths solidified with their countless retellings — but, really, how dare anyone doubt a sage? He lied about high school grades he never obtained, college courses never taken, daring rescues never made, and those are just the easiest to fact-check. Whenever possible, Nevala-Lee corrects Fuller as he cites him, the embellished version followed by the correct, less glamorous version. At other times, the reader is left wondering if what’s written on the page really happened.

It just so happens Fuller’s popular legacy is bloated, like the geodesic domes he is most easily identified with today. Alec Nevala-Lee’s new biography, Inventor of the Future, fact-checks Fuller’s legend and then corrects the record. Nevala-Lee himself discovered Fuller through the pages of the counterculture bible, Whole Earth Catalog, and grew up admiring him. But, in writing Fuller’s biography, he resists the hypnotic whirlpool surrounding Fuller. Known to be an unreliable narrator of his own life, Fuller inflated numbers, misrepresented facts, and invented stories of epiphanies and revelations. The legends and myths solidified with their countless retellings — but, really, how dare anyone doubt a sage? He lied about high school grades he never obtained, college courses never taken, daring rescues never made, and those are just the easiest to fact-check. Whenever possible, Nevala-Lee corrects Fuller as he cites him, the embellished version followed by the correct, less glamorous version. At other times, the reader is left wondering if what’s written on the page really happened.

More here.

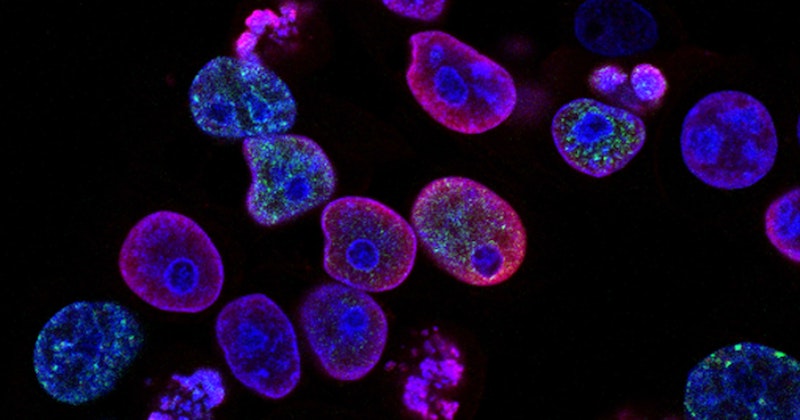

Nick Lane: Why Conventional Wisdom About Cancer Can Be Misleading

Nick Lane at Literary Hub:

The idea that mutations cause cancer remains the dominant paradigm. A special issue of Nature from 2020 wrote: “Cancer is a disease of the genome, caused by a cell’s acquisition of somatic mutations in key cancer genes.” Yet over the last decade it has looked as if the juggernaut has rolled too far. It has certainly failed to deliver on its promise in terms of therapies. So why hasn’t the death rate from malignant cancer changed since 1971?

The idea that mutations cause cancer remains the dominant paradigm. A special issue of Nature from 2020 wrote: “Cancer is a disease of the genome, caused by a cell’s acquisition of somatic mutations in key cancer genes.” Yet over the last decade it has looked as if the juggernaut has rolled too far. It has certainly failed to deliver on its promise in terms of therapies. So why hasn’t the death rate from malignant cancer changed since 1971?

The oncogene paradigm is not actually wrong, but neither is it the whole truth. Oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes certainly do mutate, and they certainly can drive cancer, but the context is far more important than the paradigm might imply. We are not immune to dogmas even today, and the idea that cancer is a disease of the genome is too close to dogma. Biology is not only about information. Just as human delinquency cannot be blamed on individuals only, but partly reflects the society in which we live, so the effects of oncogenes said to cause cancer are not set in stone, but take their meaning from the environment.

More here.

The crisis mindset is a finite resource — and we’ve exhausted it

Taylor Dotson in The New Atlantis:

In 1968, Paul Ehrlich predicted impending famine and social collapse driven by overpopulation. He compared the threat to a ticking bomb — the “population bomb.” And the claim that only a few years remain to prevent climate doom has become a familiar refrain. The recent film Don’t Look Up, about a comet barreling toward Earth, is obviously meant as an allegory for climate catastrophe.

But catastrophism fails to capture the complexities of problems that play out over a long time scale, like Covid and climate change. In a tornado or a flood, which are not only undeniably serious but also require immediate action to prevent destruction, people drop political disputes to do what is necessary to save lives. They bring their loved ones to higher ground. They stack sandbags. They gather in tornado shelters. They evacuate. Covid began as a flood in early 2020, but once a danger becomes long and grinding, catastrophism loses its purchase, and more measured public thinking is required.

More here.

John Allen Paulos: Who’s Counting? Uniting Numbers and Narratives

The Myths of Lady Rochford, the Tudor Noblewoman Who Supposedly Betrayed George and Anne Boleyn

Meilan Solly in Smithsonian:

In popular culture, Tudor noblewoman Jane Boleyn is often portrayed as a petty, jealous schemer who played a pivotal role in the downfall of Anne Boleyn, the second of Henry VIII’s six wives. According to historians and fiction writers alike, Jane (also known as Viscountess or Lady Rochford) provided damning testimony that sent her husband, George, and his sister Anne to the executioner’s block on charges of adultery and incest in May 1536.

In popular culture, Tudor noblewoman Jane Boleyn is often portrayed as a petty, jealous schemer who played a pivotal role in the downfall of Anne Boleyn, the second of Henry VIII’s six wives. According to historians and fiction writers alike, Jane (also known as Viscountess or Lady Rochford) provided damning testimony that sent her husband, George, and his sister Anne to the executioner’s block on charges of adultery and incest in May 1536.

This betrayal—supposedly motivated by her distaste for George and jealousy over his close relationship with Anne—has tainted Jane’s reputation for centuries, with one Elizabethan writer labeling her a “wicked wife, accuser of her own husband, even to the seeking of his own blood,” who acted “more to be rid of him than of true ground against him.”

More here.

Stuck With Trump

David Frum in The Atlantic:

You might think that the FBI search at Mar-a-Lago yesterday would provide a welcome opportunity for a Trump-weary Republican Party. This would be an entirely postpresidential scandal for Donald Trump. Unlike his two impeachments, this time any legal jeopardy is a purely personal Trump problem. Big donors and Fox News management have been trying for months to nudge the party away from Trump. Here was the perfect chance. Just say “No comment” and let justice take its course.

You might think that the FBI search at Mar-a-Lago yesterday would provide a welcome opportunity for a Trump-weary Republican Party. This would be an entirely postpresidential scandal for Donald Trump. Unlike his two impeachments, this time any legal jeopardy is a purely personal Trump problem. Big donors and Fox News management have been trying for months to nudge the party away from Trump. Here was the perfect chance. Just say “No comment” and let justice take its course.

But that was not to be.

The former president has discovered a new test of power: using his own misconduct to compel party leaders to rally to him. One by one, they have executed the ritual of submission: Kevin McCarthy, Marco Rubio, even the would-be Trump replacer Ron DeSantis. Maybe they’re inwardly hoping the FBI will do for them what they are too weak and frightened to do for themselves. But outwardly, they are all indignation and threats of retribution

More here.

Tuesday, August 9, 2022

Jana Prikryl’s ‘Midwood’

Dustin Illingworth at Poetry Magazine:

For artists, middle age is freighted with aesthetic drama. For poets, it’s also often a period of formal metamorphoses. Midlife crisis is a term too loaded with risible associations to be useful here. The transformation seems more a matter of taking inventory, the poet alighting on a doubt or an intuition and having a good look around. Evolutions during this period are frequent and substantial: the seriocomic alibi of Brazil in Elizabeth Bishop’s Questions of Travel (1965), the plastic pharmacopoeia of Frederick Seidel’s Sunrise (1979), Les Murray’s confessional word machines in Subhuman Redneck Poems (1996), and Karen Solie’s eschewing of the hard-luck plains in The Caiplie Caves (2019). Each represents a significant departure written during the poet’s middle years. Here the provisional conclusions of the early work lie exhausted, and the delights and disappointments of a late style are as yet undisclosed. Such an interim invites its own risks and abdications. It is simultaneously a little death and a return to life.

For artists, middle age is freighted with aesthetic drama. For poets, it’s also often a period of formal metamorphoses. Midlife crisis is a term too loaded with risible associations to be useful here. The transformation seems more a matter of taking inventory, the poet alighting on a doubt or an intuition and having a good look around. Evolutions during this period are frequent and substantial: the seriocomic alibi of Brazil in Elizabeth Bishop’s Questions of Travel (1965), the plastic pharmacopoeia of Frederick Seidel’s Sunrise (1979), Les Murray’s confessional word machines in Subhuman Redneck Poems (1996), and Karen Solie’s eschewing of the hard-luck plains in The Caiplie Caves (2019). Each represents a significant departure written during the poet’s middle years. Here the provisional conclusions of the early work lie exhausted, and the delights and disappointments of a late style are as yet undisclosed. Such an interim invites its own risks and abdications. It is simultaneously a little death and a return to life.

more here.

Poetry: Jana Prikryl

On Sarah Derbew’s “Untangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity”

Najee Olya at the LARB:

Derbew’s book arrives at a pivotal moment in classical studies. The past years have seen debates on the whiteness of the discipline and calls to burn the field down. The very term “classics” has come under fire for its perceived elitism and opacity, with eminent departments (including Berkeley’s) abandoning the name. Some have criticized the field’s intense focus on ancient Greek and Latin at the expense of archaeology, the ancient Mediterranean outside Greece and Rome, and the interdisciplinarity that forms the foundation of research like Derbew’s. Perhaps unsurprisingly, attempts to broaden the boundaries of the discipline have drawn fire from some quarters. The recent reworking of Princeton’s undergraduate language requirements in classics, for example, has become grist for the culture warrior’s mill. Yet what Sarah Derbew has accomplished is a testament to the kind of innovative work one can do by combining traditional philological rigor with fresh and novel thinking.

Derbew’s book arrives at a pivotal moment in classical studies. The past years have seen debates on the whiteness of the discipline and calls to burn the field down. The very term “classics” has come under fire for its perceived elitism and opacity, with eminent departments (including Berkeley’s) abandoning the name. Some have criticized the field’s intense focus on ancient Greek and Latin at the expense of archaeology, the ancient Mediterranean outside Greece and Rome, and the interdisciplinarity that forms the foundation of research like Derbew’s. Perhaps unsurprisingly, attempts to broaden the boundaries of the discipline have drawn fire from some quarters. The recent reworking of Princeton’s undergraduate language requirements in classics, for example, has become grist for the culture warrior’s mill. Yet what Sarah Derbew has accomplished is a testament to the kind of innovative work one can do by combining traditional philological rigor with fresh and novel thinking.

more here.

The Mysterious Dance of the Cricket Embryos: The secret is geometry

Siobhan Roberts in The New York Times:

Humans, frogs and many other widely studied animals start as a single cell that immediately divides again and again into separate cells. In crickets and most other insects, initially just the cell nucleus divides, forming many nuclei that travel throughout the shared cytoplasm and only later form cellular membranes of their own. In 2019, Stefano Di Talia, a quantitative developmental biologist at Duke University, studied the movement of the nuclei in the fruit fly and showed that they are carried along by pulsing flows in the cytoplasm — a bit like leaves traveling on the eddies of a slow-moving stream.

Humans, frogs and many other widely studied animals start as a single cell that immediately divides again and again into separate cells. In crickets and most other insects, initially just the cell nucleus divides, forming many nuclei that travel throughout the shared cytoplasm and only later form cellular membranes of their own. In 2019, Stefano Di Talia, a quantitative developmental biologist at Duke University, studied the movement of the nuclei in the fruit fly and showed that they are carried along by pulsing flows in the cytoplasm — a bit like leaves traveling on the eddies of a slow-moving stream.

But some other mechanism was at work in the cricket embryo. The researchers spent hours watching and analyzing the microscopic dance of nuclei: glowing nubs dividing and moving in a puzzling pattern, not altogether orderly, not quite random, at varying directions and speeds, neighboring nuclei more in sync than those farther away. The performance belied a choreography beyond mere physics or chemistry.

“The geometries that the nuclei come to assume are the result of their ability to sense and respond to the density of other nuclei near to them,” Dr. Extavour said. Dr. Di Talia was not involved in the new study but found it moving. “It’s a beautiful study of a beautiful system of great biological relevance,” he said.

More here.

Cancer research beset by a Gordian Knot of problems

Wafik El-Deiry in The Cancer Letter:

Some, including me, may be suffering from Chronic Password Fatigue Syndrome (CPFS would be the acronym). Scientific publishing, peer review and paywalls are a very problematic area that contributes to disparities around the world, among other disparities in research and clinical oncology that I have previously pointed out. Irreproducibility of scientific results has gotten lots of attention, although real solutions have yet to address the problem. As one thinks about how we got here, it helps to have lived through the evolution and to have a foot in both medicine and science. Actually, more than a foot. What follows is opinion but maybe it will help connect some dots.

Some, including me, may be suffering from Chronic Password Fatigue Syndrome (CPFS would be the acronym). Scientific publishing, peer review and paywalls are a very problematic area that contributes to disparities around the world, among other disparities in research and clinical oncology that I have previously pointed out. Irreproducibility of scientific results has gotten lots of attention, although real solutions have yet to address the problem. As one thinks about how we got here, it helps to have lived through the evolution and to have a foot in both medicine and science. Actually, more than a foot. What follows is opinion but maybe it will help connect some dots.

In the mid- to late-1990s, HIPAA privacy rules came on the scene, due to efforts by Hillary Clinton and others. Having completed medical school in Miami, medicine and oncology training at Johns Hopkins, and having started a faculty position at University of Pennsylvania before HIPAA, I can assure anyone reading this that there was no major deluge of privacy violations.

There were some anecdotes where some nosy people looked at health records of celebrities, and there was some concern by the early- to mid-1990’s that genetic information may be used against people who would be discriminated against by employers or insurance companies. But there has been a law against genetic discrimination, and it’s a good law, separate from HIPAA. Hillary meant well, but no one anticipated the downside of HIPAA.

More here.

The Wondrous and Mundane Diaries of Edna St. Vincent Millay

Apoorva Tadepalli in The Nation:

On April 3, 1911, Edna St. Vincent Millay took her first lover. She was 19 years old, and she engaged herself to this man with a ring that “came to me in a fortune-cake” and was “the symbol of all earthly happiness.” Millay had just graduated from high school and had taken charge of running the household while her mother worked as a traveling nurse. She fixed her younger sisters dinner, washed and mended all their clothes, and entertained their guests. Her lover had no name and no body; he was a figment she’d conjured up to help her get through the stress and loneliness of being a teenage caretaker. This first lover, her “shadow,” is not often recounted among the many others she later had, but Millay had various ways of making these exhausting days of her early adulthood endlessly charming and alive. In one note to her lover, she describes the chafing dish she served her siblings’ dinner on, which she called James, and jokes, “Why don’t you come over some evening and have something on ‘James’—doesn’t that sound dreadful—‘have something on James’!”

On April 3, 1911, Edna St. Vincent Millay took her first lover. She was 19 years old, and she engaged herself to this man with a ring that “came to me in a fortune-cake” and was “the symbol of all earthly happiness.” Millay had just graduated from high school and had taken charge of running the household while her mother worked as a traveling nurse. She fixed her younger sisters dinner, washed and mended all their clothes, and entertained their guests. Her lover had no name and no body; he was a figment she’d conjured up to help her get through the stress and loneliness of being a teenage caretaker. This first lover, her “shadow,” is not often recounted among the many others she later had, but Millay had various ways of making these exhausting days of her early adulthood endlessly charming and alive. In one note to her lover, she describes the chafing dish she served her siblings’ dinner on, which she called James, and jokes, “Why don’t you come over some evening and have something on ‘James’—doesn’t that sound dreadful—‘have something on James’!”

More here.