Pankaj Mishra and Ali Sethi in The Guardian:

In a remarkable document from the 13th century, a Sufi writer records his epiphany about the prophet Muhammad granting permission to music in India. Quoting an enigmatic utterance of the prophet (“I sense the breath of the Merciful coming from Yemen”), he speculates that the “Yemen” in question is not just the region in the Arabian peninsula, but possibly also the popular Indian raga of the same name. These days, such an innocuous interpretation, linking the founder of Islam to northern Indian music, is certain to incite charges of blasphemy, and perhaps even calls for assassination, across many Muslim populations.

In a remarkable document from the 13th century, a Sufi writer records his epiphany about the prophet Muhammad granting permission to music in India. Quoting an enigmatic utterance of the prophet (“I sense the breath of the Merciful coming from Yemen”), he speculates that the “Yemen” in question is not just the region in the Arabian peninsula, but possibly also the popular Indian raga of the same name. These days, such an innocuous interpretation, linking the founder of Islam to northern Indian music, is certain to incite charges of blasphemy, and perhaps even calls for assassination, across many Muslim populations.

But it would have been uncontroversial, even unremarkable, during much of the last millennium, the centuries during which India was the world’s busiest crossroads, receiving and transmitting cultural influences between east and west, north and south. Artists and thinkers in this time, when India played easy-going host to a polyphony of identities, were oblivious to today’s hotly invoked distinctions of religion and gender.

More here.

Most of us over the age of 30 can remember the family doctor we had when we were kids. They met us as babies and watched us grow up. They knew our stories, those of our siblings, our parents and often our grandparents, too. These stories were fundamental to the bond of trust between doctors and their patients. We are now learning that this deep, accumulated knowledge was also palpably beneficial in medical terms.

Most of us over the age of 30 can remember the family doctor we had when we were kids. They met us as babies and watched us grow up. They knew our stories, those of our siblings, our parents and often our grandparents, too. These stories were fundamental to the bond of trust between doctors and their patients. We are now learning that this deep, accumulated knowledge was also palpably beneficial in medical terms. Know thyself” is a terrific idea. It’s one of the Delphic maxims—alongside “certainty brings insanity” and “nothing to excess”—that you can find inscribed on the Temple of Apollo. Such knowing could well begin with an evolutionary conundrum: menopause. It’s as if natural selection took “nothing to excess” strangely to heart in the realm of human reproduction. Very few mammals—excepting short-finned pilot whales and possibly Asian elephants—experience anything like a prolonged life stage during which they are alive yet nonbreeding. So long as they draw breath, our fellow mammals release eggs. But not Homo sapiens.

Know thyself” is a terrific idea. It’s one of the Delphic maxims—alongside “certainty brings insanity” and “nothing to excess”—that you can find inscribed on the Temple of Apollo. Such knowing could well begin with an evolutionary conundrum: menopause. It’s as if natural selection took “nothing to excess” strangely to heart in the realm of human reproduction. Very few mammals—excepting short-finned pilot whales and possibly Asian elephants—experience anything like a prolonged life stage during which they are alive yet nonbreeding. So long as they draw breath, our fellow mammals release eggs. But not Homo sapiens. The logic behind [interest] rate rises is that making the credit of the nations’ poor more, while they are already struggling with food and fuel bills, will make them in the long run better off.

The logic behind [interest] rate rises is that making the credit of the nations’ poor more, while they are already struggling with food and fuel bills, will make them in the long run better off. Last year, the particle physicist

Last year, the particle physicist  Cities that are attacked by nuclear missiles burn at such an intensity that they create their own wind system, a firestorm: hot air above the burning city ascends and is replaced by air that rushes in from all directions. The storm-force winds fan the flames and create immense heat.

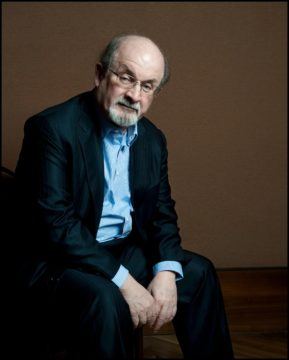

Cities that are attacked by nuclear missiles burn at such an intensity that they create their own wind system, a firestorm: hot air above the burning city ascends and is replaced by air that rushes in from all directions. The storm-force winds fan the flames and create immense heat. The attack on Rushdie is a wake-up call for all of us who have a stake in free expression, which is all of us, period. While we do not yet know the motives of his attackers, it is hard to envisage a scenario in which this brazen, premeditated attack, the first in memory targeting a writer at a literary event in the United States, had nothing to do with Rushdie’s words and ideas.

The attack on Rushdie is a wake-up call for all of us who have a stake in free expression, which is all of us, period. While we do not yet know the motives of his attackers, it is hard to envisage a scenario in which this brazen, premeditated attack, the first in memory targeting a writer at a literary event in the United States, had nothing to do with Rushdie’s words and ideas. The terrorist assault on Salman Rushdie on Friday morning, in western New York, was triply horrific to contemplate. First in its sheer brutality and cruelty, on a seventy-five-year-old man, unprotected and about to speak—doubtless cheerfully and eloquently, as he always did—repeatedly in the stomach and neck and face. Indeed, we accept the abstraction of those words—“assaulted” and “attacked”—too casually. To try to feel the victim’s feelings—first shock, then unimaginable pain, then the panicked sense of life bleeding away—to engage in the most moderate empathy with the author is to be oneself scarred. (At the time of writing, Rushdie is reportedly on a ventilator, with an uncertain future, the only certainty being that, if he lives, he will be maimed for life.)

The terrorist assault on Salman Rushdie on Friday morning, in western New York, was triply horrific to contemplate. First in its sheer brutality and cruelty, on a seventy-five-year-old man, unprotected and about to speak—doubtless cheerfully and eloquently, as he always did—repeatedly in the stomach and neck and face. Indeed, we accept the abstraction of those words—“assaulted” and “attacked”—too casually. To try to feel the victim’s feelings—first shock, then unimaginable pain, then the panicked sense of life bleeding away—to engage in the most moderate empathy with the author is to be oneself scarred. (At the time of writing, Rushdie is reportedly on a ventilator, with an uncertain future, the only certainty being that, if he lives, he will be maimed for life.) One of the stranger sights on the University College London campus is the clothed skeleton of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Stranger still is that a waxwork head sits on its shoulders, where Bentham’s own head should be, as per his will. Meanwhile, his preserved head is elsewhere – his friends thought it looked too grotesque for display, and commissioned the waxwork one instead. Legend has it that Bentham’s real head was stolen by some students from King’s College London as a prank against their University College rivals, and a ransom demanded for returning it. Apparently, this was eventually paid up, and the head was returned.

One of the stranger sights on the University College London campus is the clothed skeleton of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Stranger still is that a waxwork head sits on its shoulders, where Bentham’s own head should be, as per his will. Meanwhile, his preserved head is elsewhere – his friends thought it looked too grotesque for display, and commissioned the waxwork one instead. Legend has it that Bentham’s real head was stolen by some students from King’s College London as a prank against their University College rivals, and a ransom demanded for returning it. Apparently, this was eventually paid up, and the head was returned. Branko Milanovic over at his substack Global Inequality and More 3.0:

Branko Milanovic over at his substack Global Inequality and More 3.0: Terry Eagleton in Sidecar [h/t: Leonard Benardo]:

Terry Eagleton in Sidecar [h/t: Leonard Benardo]: Gregg studies animal behavior and is an expert in dolphin communication. He shows how human cognition is extraordinarily complex, allowing us to paint pictures and write symphonies. We can share ideas with one another so that we don’t have to rely only on gut instinct or direct experience in order to learn. But this compulsion to learn can be superfluous, he says. We accumulate what the philosopher Ruth Garrett Millikan calls “dead facts” — knowledge about the world that is useless for daily living, like the distance to the moon, or what happened in the latest episode of “Succession.” Our collections of dead facts, Gregg writes, “help us to imagine an infinite number of solutions to whatever problems we encounter — for good or ill.”

Gregg studies animal behavior and is an expert in dolphin communication. He shows how human cognition is extraordinarily complex, allowing us to paint pictures and write symphonies. We can share ideas with one another so that we don’t have to rely only on gut instinct or direct experience in order to learn. But this compulsion to learn can be superfluous, he says. We accumulate what the philosopher Ruth Garrett Millikan calls “dead facts” — knowledge about the world that is useless for daily living, like the distance to the moon, or what happened in the latest episode of “Succession.” Our collections of dead facts, Gregg writes, “help us to imagine an infinite number of solutions to whatever problems we encounter — for good or ill.” The more we learn about the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago, the sillier — and more sinister — the overcaffeinated Republican defenses of former president Donald Trump look. A genius-level spinmeister, Trump set the tone with a

The more we learn about the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago, the sillier — and more sinister — the overcaffeinated Republican defenses of former president Donald Trump look. A genius-level spinmeister, Trump set the tone with a