Morgan Meis at Slant Books:

I was meeting my mother at the museum. My mother is both a great lover of art and completely unpretentious about it. Often, she simply stands in front of objects of art and smiles. We found ourselves in an exhibit entitled Indian Skies: The Howard Hodgkin Collection of Indian Court Painting. We were both suddenly astonished. I don’t know why exactly. I do know why un-exactly. The paintings are extraordinary. But what does that mean? I don’t know. I don’t know anything about Indian Court paintings. I’ve seen a few here and there, including some in India. But I don’t know how to look at them. I don’t know the history or the context or the way that these paintings fit into a narrative. I don’t know the codes. So I just looked, without context, without codes.

I was meeting my mother at the museum. My mother is both a great lover of art and completely unpretentious about it. Often, she simply stands in front of objects of art and smiles. We found ourselves in an exhibit entitled Indian Skies: The Howard Hodgkin Collection of Indian Court Painting. We were both suddenly astonished. I don’t know why exactly. I do know why un-exactly. The paintings are extraordinary. But what does that mean? I don’t know. I don’t know anything about Indian Court paintings. I’ve seen a few here and there, including some in India. But I don’t know how to look at them. I don’t know the history or the context or the way that these paintings fit into a narrative. I don’t know the codes. So I just looked, without context, without codes.

More here.

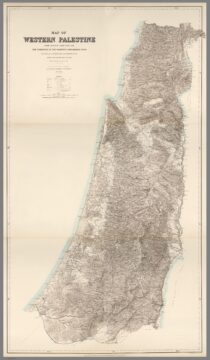

Palestine, before it named something else, named a region. The region emerged during Ottoman rule, between 1518 and 1920. It was called Filastin in Arabic, the language of the Muslims, Christians, Jews and others who lived in this region. The word « Palestinians » could apply to all of them. It could refer to « Palestinians » beyond Palestine, too, as when Immanuel Kant, for example, referred to European Jews in 1798 as « Palestinians living among us » in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. This is one of many things we’ve forgotten to remember.

Palestine, before it named something else, named a region. The region emerged during Ottoman rule, between 1518 and 1920. It was called Filastin in Arabic, the language of the Muslims, Christians, Jews and others who lived in this region. The word « Palestinians » could apply to all of them. It could refer to « Palestinians » beyond Palestine, too, as when Immanuel Kant, for example, referred to European Jews in 1798 as « Palestinians living among us » in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. This is one of many things we’ve forgotten to remember. If science has a native tongue, it is mathematics. Equations capture, precisely, the relationships among the elements of a system; they allow us to pose questions and calculate answers. Numerically, these answers are precise and unambiguous – but what happens when we want to know what our calculations mean? Well, that is when we revert to our own native tongue: metaphor.

If science has a native tongue, it is mathematics. Equations capture, precisely, the relationships among the elements of a system; they allow us to pose questions and calculate answers. Numerically, these answers are precise and unambiguous – but what happens when we want to know what our calculations mean? Well, that is when we revert to our own native tongue: metaphor. An orangutan in Sumatra surprised scientists when he was seen treating an open wound on his cheek with a poultice made from a medicinal plant. It’s the first scientific record of a wild animal healing a wound using a plant with known medicinal properties. The findings were published this week in Scientific Reports

An orangutan in Sumatra surprised scientists when he was seen treating an open wound on his cheek with a poultice made from a medicinal plant. It’s the first scientific record of a wild animal healing a wound using a plant with known medicinal properties. The findings were published this week in Scientific Reports O

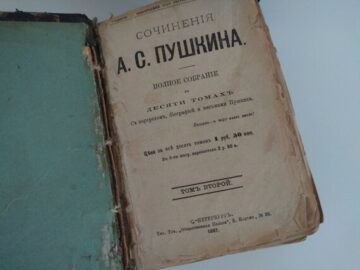

O In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books.

In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books. Former President Donald Trump testified in the New York civil fraud trial, earning rebukes from the judge for his off-topic comments. In the editorial cartoon gallery’s lead image, Nick Anderson pokes fun at Trump’s courtroom theatrics by showing him descending a golden escalator to the witness stand, a visual reference to the announcement at Trump Tower of his first presidential bid.

Former President Donald Trump testified in the New York civil fraud trial, earning rebukes from the judge for his off-topic comments. In the editorial cartoon gallery’s lead image, Nick Anderson pokes fun at Trump’s courtroom theatrics by showing him descending a golden escalator to the witness stand, a visual reference to the announcement at Trump Tower of his first presidential bid. Quick pop quiz: Prior to this week, what was Taylor Swift’s last new No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100?

Quick pop quiz: Prior to this week, what was Taylor Swift’s last new No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100? In China we have a saying that reading a banned book on a snowy night is one of the true joys of life. From this, one can well imagine the kind of satisfaction that reading a banned book may bring—like candy locked up in a cabinet, it releases a sweet fragrance into solitary spaces. Whenever I travel abroad, I am invariably introduced as China’s most controversial and most censored author. I neither agree nor disagree with this characterization—I’m not bothered by it, but neither do I feel particularly honored by it.

In China we have a saying that reading a banned book on a snowy night is one of the true joys of life. From this, one can well imagine the kind of satisfaction that reading a banned book may bring—like candy locked up in a cabinet, it releases a sweet fragrance into solitary spaces. Whenever I travel abroad, I am invariably introduced as China’s most controversial and most censored author. I neither agree nor disagree with this characterization—I’m not bothered by it, but neither do I feel particularly honored by it. The German forester Peter Wohlleben’s surprise bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees (published in English in 2016), has inaugurated a new tree discourse, which sees them not as inert objects but

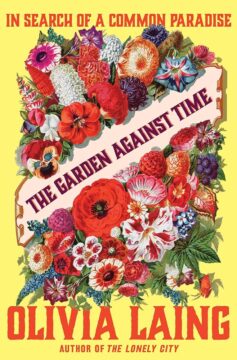

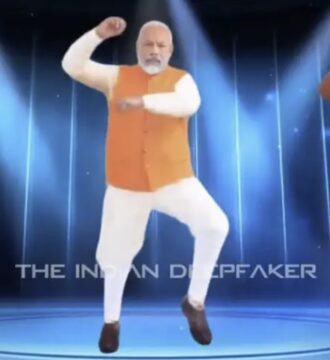

The German forester Peter Wohlleben’s surprise bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees (published in English in 2016), has inaugurated a new tree discourse, which sees them not as inert objects but  Artificial intelligence is enabling India’s politicians to be everywhere at once in the world’s largest election by cloning their voices and digital likenesses. Even dead public figures, such as politician and actress Jayaram Jayalalithaa, are getting digitally resurrected to canvass support in what is shaping up to be the biggest test yet of democratic elections in the age of

Artificial intelligence is enabling India’s politicians to be everywhere at once in the world’s largest election by cloning their voices and digital likenesses. Even dead public figures, such as politician and actress Jayaram Jayalalithaa, are getting digitally resurrected to canvass support in what is shaping up to be the biggest test yet of democratic elections in the age of  O

O