Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

We live in a dysfunctional system in which money flows out of the countries that need it most and into the coffers of the wealthiest. In 2023, the private sector collected $68 billion more in interest and principal repayments than it lent to the developing world. International financial institutions and assistance agencies extracted another $40 billion, while net concessional assistance from international financial institutions was only $2 billion—even as famine spread. The result is that as developing economies make exorbitant interest payments to their creditors, they are forced to cut spending on health, education, and infrastructure at home. Half of the world’s poorest countries are now poorer than they were before the pandemic.

At The Polycrisis we have been tracking the whipsaw of the global financial system amid private finance mantras, interest-rate hikes at the Fed, and the explosion of debt in the global South. In our dispatches on IMF meetings, the Paris conference on debt and climate, the BRICS summit, Barbados, Brussels, Ukraine, and Pakistan, we have sought to throw light on the political economy of financial distress. Who is in need? What do they get from whom, and under what conditions?

The polycentric financial “order”

The World Bank boosted its lending in the wake of the Covid pandemic, but is still well short of meeting the financing needs of developing countries. At the Spring meetings of the IMF and World Bank this week, the question of who adds capital for development, climate resilience, and the energy transition is high on the agenda.

Long-term finance is one thing, but in a crisis, it’s liquidity that counts most—and it can be key to warding off the kind of panic that drives investment away.

In all this, the dollar remains king. Want to make payments? Send an invoice? Store your wealth? Borrow across borders? Chatter about any replacement of the dollar as the dominant reserve currency is overblown. No other contender is willing to run the current-account deficit necessary to be a global reserve issuer. And when a storm arrives, liquidity flows to those with “safe assets” closest to the imperial core, while the burden of “structural adjustment” falls on the poorest and weakest shoulders in each society.

More here.

Editor-in-chief Sarahanne Field describes herself and her team at the Journal of Trial & Error as wanting to highlight the “ugly side of science — the parts of the process that have gone wrong”.

Editor-in-chief Sarahanne Field describes herself and her team at the Journal of Trial & Error as wanting to highlight the “ugly side of science — the parts of the process that have gone wrong”. Richard Pithouse: Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, suddenly opening up the field of political possibility after a long and exhausting stalemate between the progressive forces, which were largely organized in two groups: the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the trade unions, and the apartheid state. What did Mandela’s release mean to you?

Richard Pithouse: Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, suddenly opening up the field of political possibility after a long and exhausting stalemate between the progressive forces, which were largely organized in two groups: the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the trade unions, and the apartheid state. What did Mandela’s release mean to you? In the years following American independence, many questions would be asked, in different spheres, of what it meant to be a citizen, and

In the years following American independence, many questions would be asked, in different spheres, of what it meant to be a citizen, and  Longevity and eternal youth have frequently been sought after down through the ages, and efforts to keep from dying and fight off age have a long and interesting history.

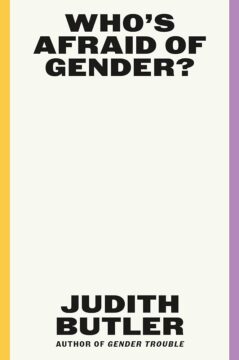

Longevity and eternal youth have frequently been sought after down through the ages, and efforts to keep from dying and fight off age have a long and interesting history. Butler is soft-spoken and gallant, often sheathed in a trim black blazer or a leather jacket, but, given the slightest encouragement, they turn goofy and sly, almost gratefully. When they were twelve years old, they identified two plausible professional paths: philosopher or clown. In ordinary life, Butler incorporates both.

Butler is soft-spoken and gallant, often sheathed in a trim black blazer or a leather jacket, but, given the slightest encouragement, they turn goofy and sly, almost gratefully. When they were twelve years old, they identified two plausible professional paths: philosopher or clown. In ordinary life, Butler incorporates both.

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by the late actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures aiming to solve the problem of death as if it were just an upgrade to your smartphone’s operating system.

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by the late actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures aiming to solve the problem of death as if it were just an upgrade to your smartphone’s operating system. As the historian Nell Irvin Painter has learned over the course of her eight decades on this earth, inspiration can come from some unlikely places.

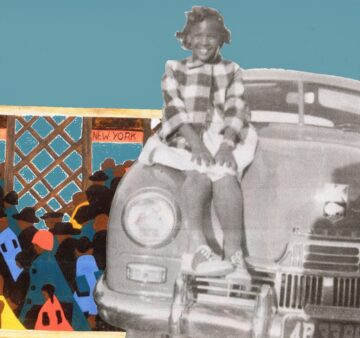

As the historian Nell Irvin Painter has learned over the course of her eight decades on this earth, inspiration can come from some unlikely places.