Jesse Singal in The Spectator:

What usually happens is this: some academic or other thinker or creative type is cheerfully chugging along in their career, living and working in progressive spaces. Maybe he is a professor, maybe he is a TV writer. Then, he commits some offence, or is perceived as having done so, and suddenly faces an onslaught of censure. Sometimes the opprobrium is wildly disproportionate to the offence. And there’s a very real walls-closing-in feeling, because the hate is coming from people he viewed as members of his ‘tribe,’ sometimes friends or close colleagues.

What usually happens is this: some academic or other thinker or creative type is cheerfully chugging along in their career, living and working in progressive spaces. Maybe he is a professor, maybe he is a TV writer. Then, he commits some offence, or is perceived as having done so, and suddenly faces an onslaught of censure. Sometimes the opprobrium is wildly disproportionate to the offence. And there’s a very real walls-closing-in feeling, because the hate is coming from people he viewed as members of his ‘tribe,’ sometimes friends or close colleagues.

These campaigns, I know from first- and second-hand experience, almost always involve sociopathic backchannel efforts to cut the victims off from their social and professional networks; anyone who is seen as ‘defending’ them (by questioning the charges or the punishment at all) risks getting subsequently un-personed themselves. So, many people denounce or ignore their friends, rather than sticking up for them.

More here.

Cities are, indeed, the opposite of natural ecosystems. Net sinks of energy and materials, they are hot, noisy, poisonous and dangerous. They are constantly changing, often for frivolous or even wasteful reasons. Very few non-human species can cope with such chaos and stay away. Some species, however, see opportunities where others find only disturbance and stress. Cities offer countless productive chances for those willing and able to adapt. Those that take up this challenge share several crucial characteristics, including: already being abundant in the neighbouring landscape (10), having a generalised diet (with granivores being at a great advantage given the ubiquity of feeders)(11), demonstrating innovative foraging capacity and often belonging to groups with proportionally larger brains (12). Clearly, the latter two features go hand in hand.

Cities are, indeed, the opposite of natural ecosystems. Net sinks of energy and materials, they are hot, noisy, poisonous and dangerous. They are constantly changing, often for frivolous or even wasteful reasons. Very few non-human species can cope with such chaos and stay away. Some species, however, see opportunities where others find only disturbance and stress. Cities offer countless productive chances for those willing and able to adapt. Those that take up this challenge share several crucial characteristics, including: already being abundant in the neighbouring landscape (10), having a generalised diet (with granivores being at a great advantage given the ubiquity of feeders)(11), demonstrating innovative foraging capacity and often belonging to groups with proportionally larger brains (12). Clearly, the latter two features go hand in hand. S

S I

I Manish Vira, a urologist at Northwell Health in New York performs prostate biopsy procedures three to five times a week. He inserts 12 needles into specific locations on the prostate gland, identified by MRI images that reveal malignant or suspicious lesions. The samples then go to a pathologist who determines whether cancer is present and how aggressive it is. “It’s a standard protocol,” explains Vira, who is also

Manish Vira, a urologist at Northwell Health in New York performs prostate biopsy procedures three to five times a week. He inserts 12 needles into specific locations on the prostate gland, identified by MRI images that reveal malignant or suspicious lesions. The samples then go to a pathologist who determines whether cancer is present and how aggressive it is. “It’s a standard protocol,” explains Vira, who is also  In pursuit of the natural laws of the universe, human beings have accomplished remarkable things. We’ve outlined the principles of gravity and thermodynamics. We’ve built enormous machines to dig into the deepest parts of the Earth, to understand what happens at the shortest quantum distances, and equally large machines to take pictures of the most distant parts of the cosmos. Still, there remain a number of foundational gaps in our knowledge—gaps that have allowed some wild ideas to take root. Some scientists hypothesize that, with every decision we make, our universe forks into multiverses, that consciousness arises from the quantum movements of microtubules, that the universe itself is conscious, or that there is this cat in a box and not in a box at the same time. These ideas, and related big questions about the nature of the universe, are the subject of particle physicist Sabine Hossenfelder’s new book, Existential Physics. In it, she argues that many of these far-out theories, put forward without evidence, are on par with religious belief. Physics, she contends, does not yet provide the answers to all of our questions—and it’s doubtful that it ever will.

In pursuit of the natural laws of the universe, human beings have accomplished remarkable things. We’ve outlined the principles of gravity and thermodynamics. We’ve built enormous machines to dig into the deepest parts of the Earth, to understand what happens at the shortest quantum distances, and equally large machines to take pictures of the most distant parts of the cosmos. Still, there remain a number of foundational gaps in our knowledge—gaps that have allowed some wild ideas to take root. Some scientists hypothesize that, with every decision we make, our universe forks into multiverses, that consciousness arises from the quantum movements of microtubules, that the universe itself is conscious, or that there is this cat in a box and not in a box at the same time. These ideas, and related big questions about the nature of the universe, are the subject of particle physicist Sabine Hossenfelder’s new book, Existential Physics. In it, she argues that many of these far-out theories, put forward without evidence, are on par with religious belief. Physics, she contends, does not yet provide the answers to all of our questions—and it’s doubtful that it ever will. Inside a soundproofed crate sits one of the world’s worst neural networks. After being presented with an image of the number 6, it pauses for a moment before identifying the digit: zero.

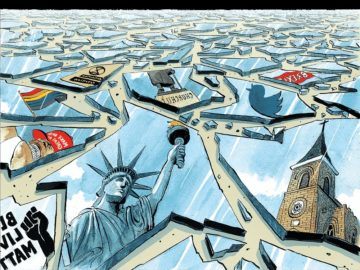

Inside a soundproofed crate sits one of the world’s worst neural networks. After being presented with an image of the number 6, it pauses for a moment before identifying the digit: zero.  We’ve got the Internet all wrong. Its raison d’être is not, as Mark Zuckerberg claims for his own corporation, to “strengthen our social fabric and bring the world closer together.” To the contrary, the Internet is a pernicious disease. It is—as Justin E.H. Smith argues in his new book, The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is—thoroughly “anti-human.”

We’ve got the Internet all wrong. Its raison d’être is not, as Mark Zuckerberg claims for his own corporation, to “strengthen our social fabric and bring the world closer together.” To the contrary, the Internet is a pernicious disease. It is—as Justin E.H. Smith argues in his new book, The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is—thoroughly “anti-human.” Very few writers in the twenty-first century are polymaths of the sort that previous centuries sometimes spawned – those who knew about all the subjects that mattered at the time, while still producing original work. Specialisation and the multiplication of fields and subfields of research, in both the humanities and the sciences, has rendered such breadth nearly impossible. Siri Hustvedt, however, is an exception: she is a polymath for our times, fluent in multiple specialised discourses, but whose mode is artistic.

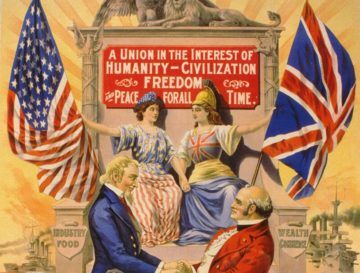

Very few writers in the twenty-first century are polymaths of the sort that previous centuries sometimes spawned – those who knew about all the subjects that mattered at the time, while still producing original work. Specialisation and the multiplication of fields and subfields of research, in both the humanities and the sciences, has rendered such breadth nearly impossible. Siri Hustvedt, however, is an exception: she is a polymath for our times, fluent in multiple specialised discourses, but whose mode is artistic. In the United States, the political baptism of the non-elites to the hegemonic mission happened in the years between 1920 and 1960. Mass culture in those crucial years paved the way for a patriotic politics built around U.S. military prowess, massive expansion of literacy and lifestyle, the phobias of the Red Scare and Jim Crow, and commercial success across the globe. By the midcentury, anti-communism produced a coordinated ideological effort at cohesion. Elites recruited the political aspirations of working-class and middle-class voters into the cause of American supremacy, framing the export of American consumer capitalism as the triple gift of sacred freedom, true democracy, and general prosperity. The Hollywood studio system picked up the plots of late-Victorian adventure genres, adapting them to the worldview of U.S. supremacy and global centrality.

In the United States, the political baptism of the non-elites to the hegemonic mission happened in the years between 1920 and 1960. Mass culture in those crucial years paved the way for a patriotic politics built around U.S. military prowess, massive expansion of literacy and lifestyle, the phobias of the Red Scare and Jim Crow, and commercial success across the globe. By the midcentury, anti-communism produced a coordinated ideological effort at cohesion. Elites recruited the political aspirations of working-class and middle-class voters into the cause of American supremacy, framing the export of American consumer capitalism as the triple gift of sacred freedom, true democracy, and general prosperity. The Hollywood studio system picked up the plots of late-Victorian adventure genres, adapting them to the worldview of U.S. supremacy and global centrality. Two Chinese psychologists talk about divorce, stockpiling and crying into your mask.

Two Chinese psychologists talk about divorce, stockpiling and crying into your mask. Suzanne Kahn at the Roosevelt Institute:

Suzanne Kahn at the Roosevelt Institute: Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar:

Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar: In the course of his book, Calvo describes many experiments that reveal plants’ remarkable range, including the way they communicate with others nearby using “chemical talk”, a language encoded in about 1,700 volatile organic compounds. He also shows how, like animals, they can be anaesthetised. In lectures, he places a Venus flytrap under a glass bell jar with a cotton pad soaked in anaesthetic. After an hour the plant no longer responds to touch by closing its traps. Tests show the plant’s electrical activity has stopped. It is effectively asleep, just as a cat would be. He also notes that the process of germination in seeds can be halted under anaesthetic. If plants can be put to sleep, does that imply they also have a waking state? Calvo thinks it does, for he argues that plants are not just “photosynthetic machines” and that it’s quite possible that they have an individual experience of the world: “They may be aware.”

In the course of his book, Calvo describes many experiments that reveal plants’ remarkable range, including the way they communicate with others nearby using “chemical talk”, a language encoded in about 1,700 volatile organic compounds. He also shows how, like animals, they can be anaesthetised. In lectures, he places a Venus flytrap under a glass bell jar with a cotton pad soaked in anaesthetic. After an hour the plant no longer responds to touch by closing its traps. Tests show the plant’s electrical activity has stopped. It is effectively asleep, just as a cat would be. He also notes that the process of germination in seeds can be halted under anaesthetic. If plants can be put to sleep, does that imply they also have a waking state? Calvo thinks it does, for he argues that plants are not just “photosynthetic machines” and that it’s quite possible that they have an individual experience of the world: “They may be aware.”