Category: Archives

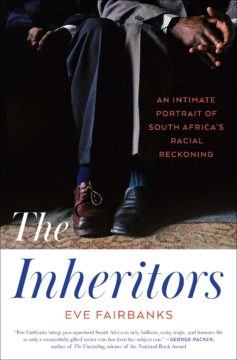

An Empathetic Account of the Complexity After Apartheid

Jennifer Szalai at the NYT:

It was nothing short of a miracle — that was what South African schoolchildren were taught when Nelson Mandela was elected president in 1994, in the country’s first fully democratic elections. Apartheid, the brutal system of white minority rule that made South Africa a global pariah, was over. As Eve Fairbanks writes in “The Inheritors,” her new book about the decades before and after that transition, its miraculousness “was like mathematics, amazing but incontrovertible.”

It was nothing short of a miracle — that was what South African schoolchildren were taught when Nelson Mandela was elected president in 1994, in the country’s first fully democratic elections. Apartheid, the brutal system of white minority rule that made South Africa a global pariah, was over. As Eve Fairbanks writes in “The Inheritors,” her new book about the decades before and after that transition, its miraculousness “was like mathematics, amazing but incontrovertible.”

But Malaika, one of the central figures in this account, remembers that her teachers’ soaring language seemed completely out of step with what she endured in her daily life. Born a few years before the end of apartheid, she continued to live in a shack in Soweto, a Black township on the outskirts of Johannesburg. She and her mother, Dipuo, were still poor.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Two Voices

Poet to Friend

If I believed

My caring would relieve your pain

I would be by you forever

But I know

My sympathy is in vain

I do not have the cure you need

Only you can heal yourself

Only you

Friend to Poet

If I believed

There were a cure

Would I ask you

To be by me forever

Is it possible I seek

Something else altogether

Only you can think that through

Only you

by Anjum Altaf

from More Transgressions

LG Publishers, Delhi, 2021

___________

mire hamdam mire dost.

Translations in Shiv Kumar, Victor Kierman

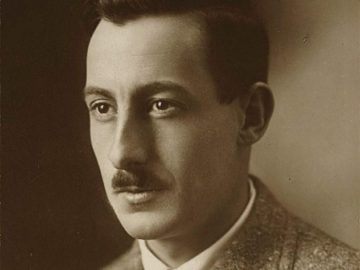

Milman Parry Brief life of a Homeric scholar with a big idea

Robert Kanigel in Harvard Magazine:

MILMAN PARRY saw the Homeric epics through new eyes, heard them through new ears. The Iliad and the Odyssey, he said, were the work of generations of illiterate poets who composed orally; their poetry took wing in the moment, were reduced to print only centuries later. The demands of their poetic rhythm, thedum-diddy, dum-diddy of dactylic hexameter, ruled their word choice as much as the gods, heroes, and epic stories they depicted. As a 21-year-old graduate student of Greek at the University of California at Berkeley, Parry, the son of an Oakland pharmacist and the first of his family to attend college, flirted with an early version of this idea in the summer of 1923. It became a succinct master’s thesis that soon was consigned to the library stacks and forgotten. The following year, with his wife, Marian, and their infant daughter, Parry went to Paris, worked on his French, enrolled at the Sorbonne and, under the tutelage of French scholars, refined and expanded his idea into an intricately argued doctoral thesis.

MILMAN PARRY saw the Homeric epics through new eyes, heard them through new ears. The Iliad and the Odyssey, he said, were the work of generations of illiterate poets who composed orally; their poetry took wing in the moment, were reduced to print only centuries later. The demands of their poetic rhythm, thedum-diddy, dum-diddy of dactylic hexameter, ruled their word choice as much as the gods, heroes, and epic stories they depicted. As a 21-year-old graduate student of Greek at the University of California at Berkeley, Parry, the son of an Oakland pharmacist and the first of his family to attend college, flirted with an early version of this idea in the summer of 1923. It became a succinct master’s thesis that soon was consigned to the library stacks and forgotten. The following year, with his wife, Marian, and their infant daughter, Parry went to Paris, worked on his French, enrolled at the Sorbonne and, under the tutelage of French scholars, refined and expanded his idea into an intricately argued doctoral thesis.

In 1928, he returned to the United States and, after a year on the faculty of a small midwestern college, took a position at Harvard, as instructor in Greek and Latin and tutor in the Division of Ancient Languages. He remained at Harvard for the rest of his brief life, which ended in 1935 with the blast of a revolver in a Los Angeles hotel room: At the time it was judged a tragic accident. Later, some would blithely ascribe it to suicide, though the evidence is lacking. Others, within Parry’s family, would see the shooting as his wife’s doing, a moment’s raging vengeance for supposed marital cruelties.

More here.

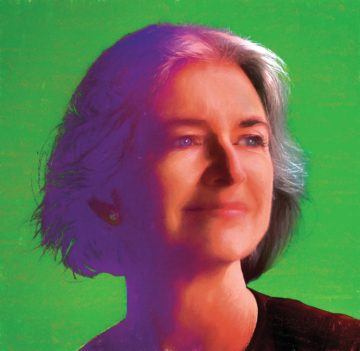

Her Discovery Changed the World. How Does She Think We Should Use It?

David Marchese in The New York Times:

It’s entirely possible, maybe even likely, that during some slow day at the lab early in her career, Jennifer Doudna, in a moment of private ambition, daydreamed about making a breakthrough that could change the world. But communicating with the world about the ethical ramifications of such a breakthrough? “Definitely not!” says Doudna, who along with Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for their research on CRISPR gene-editing technology. “I’m still on the learning curve with that.” Since 2012, when Doudna and her colleagues shared the findings of work they did on editing bacterial genes, the 58-year-old has become a leading voice in the conversation about how we might use CRISPR — uses that could, and probably will, include tweaking crops to become more drought resistant, curing genetically inheritable medical disorders and, most controversial, editing human embryos. “It’s a little scary, quite honestly,” Doudna says about the possibilities of our CRISPR future. “But it’s also quite exciting.”

It’s entirely possible, maybe even likely, that during some slow day at the lab early in her career, Jennifer Doudna, in a moment of private ambition, daydreamed about making a breakthrough that could change the world. But communicating with the world about the ethical ramifications of such a breakthrough? “Definitely not!” says Doudna, who along with Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for their research on CRISPR gene-editing technology. “I’m still on the learning curve with that.” Since 2012, when Doudna and her colleagues shared the findings of work they did on editing bacterial genes, the 58-year-old has become a leading voice in the conversation about how we might use CRISPR — uses that could, and probably will, include tweaking crops to become more drought resistant, curing genetically inheritable medical disorders and, most controversial, editing human embryos. “It’s a little scary, quite honestly,” Doudna says about the possibilities of our CRISPR future. “But it’s also quite exciting.”

More here.

Friday, August 19, 2022

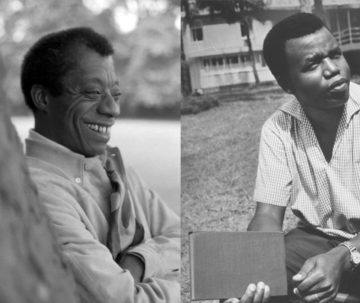

Thinking About Home and Country with Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin

Abena Ampofoa Asare in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin met for the first time at the 1980 conference of the African Language Association in Gainesville, Florida. The historic encounter between two literary giants comes to us in poignant fragments. Achebe recalled the meeting in a 2001 audio tribute for PEN America’s “A Celebration of James Baldwin: A Twentieth-Century Masters Tribute,” while Baldwin included video from the event in his 1982 documentary I Heard It Through the Grapevine. In October 2020, the University of Florida’s Center for African Studies held a commemorative conference where witnesses and scholars recalled, theorized, and celebrated these men’s first moments together.

Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin met for the first time at the 1980 conference of the African Language Association in Gainesville, Florida. The historic encounter between two literary giants comes to us in poignant fragments. Achebe recalled the meeting in a 2001 audio tribute for PEN America’s “A Celebration of James Baldwin: A Twentieth-Century Masters Tribute,” while Baldwin included video from the event in his 1982 documentary I Heard It Through the Grapevine. In October 2020, the University of Florida’s Center for African Studies held a commemorative conference where witnesses and scholars recalled, theorized, and celebrated these men’s first moments together.

Achebe and Baldwin walked parallel roads of exile. Each spent decades living outside his country’s borders. Each would die far away from home. Each never stopped writing about his birthplace, even as he pursued life despite and across national borders. At their magnetic meeting, exile, with its wounds, was the ground upon which they recognized each other as brothers.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: William MacAskill on Maximizing Good in the Present and Future

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

It’s always a little humbling to think about what affects your words and actions might have on other people, not only right now but potentially well into the future. Now take that humble feeling and promote it to all of humanity, and arbitrarily far in time. How do our actions as a society affect all the potential generations to come? William MacAskill is best known as a founder of the Effective Altruism movement, and is now the author of What We Owe the Future. In this new book he makes the case for longtermism: the idea that we should put substantial effort into positively influencing the long-term future. We talk about the pros and cons of that view, including the underlying philosophical presuppositions.

It’s always a little humbling to think about what affects your words and actions might have on other people, not only right now but potentially well into the future. Now take that humble feeling and promote it to all of humanity, and arbitrarily far in time. How do our actions as a society affect all the potential generations to come? William MacAskill is best known as a founder of the Effective Altruism movement, and is now the author of What We Owe the Future. In this new book he makes the case for longtermism: the idea that we should put substantial effort into positively influencing the long-term future. We talk about the pros and cons of that view, including the underlying philosophical presuppositions.

Mindscape listeners can get 50% off What We Owe the Future, thanks to a partnership between the Forethought Foundation and Bookshop.org. Just click here and use code MINDSCAPE50 at checkout.

More here.

The New Moral Mathematics

Kieran Setiya in the Boston Review:

What we do now affects those future people in dramatic ways: whether they will exist at all and in what numbers; what values they embrace; what sort of planet they inherit; what sorts of lives they lead. It’s as if we’re trapped on a tiny island while our actions determine the habitability of a vast continent and the life prospects of the many who may, or may not, inhabit it. What an awful responsibility.

What we do now affects those future people in dramatic ways: whether they will exist at all and in what numbers; what values they embrace; what sort of planet they inherit; what sorts of lives they lead. It’s as if we’re trapped on a tiny island while our actions determine the habitability of a vast continent and the life prospects of the many who may, or may not, inhabit it. What an awful responsibility.

This is the perspective of the “longtermist,” for whom the history of human life so far stands to the future of humanity as a trip to the chemist’s stands to a mission to Mars.

Oxford philosophers William MacAskill and Toby Ord, both affiliated with the university’s Future of Humanity Institute, coined the word “longtermism” five years ago. Their outlook draws on utilitarian thinking about morality.

More here.

Driving the Strada della Forra

Note: I drove this stretch of road yesterday. It is spectacular. Much more info here.

Anywhere but here: Where did the pandemic start?

Jon Cohen in Science:

When Alice Hughes downloaded a preprint from the server Research Square in September 2021, she could hardly believe her eyes. The study described a massive effort to survey bat viruses in China, in search of clues to the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. A team of 21 researchers from the country’s leading academic institutions had trapped more than 17,000 bats, from the subtropical south to the frigid northeast, and tested them for relatives of SARS-CoV-2.

When Alice Hughes downloaded a preprint from the server Research Square in September 2021, she could hardly believe her eyes. The study described a massive effort to survey bat viruses in China, in search of clues to the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. A team of 21 researchers from the country’s leading academic institutions had trapped more than 17,000 bats, from the subtropical south to the frigid northeast, and tested them for relatives of SARS-CoV-2.

The number they found: zero.

The authors acknowledged this was a surprising result. But they concluded relatives of SARS-CoV-2 are “extremely rare” in China and suggested that to pinpoint the pandemic’s roots, “extensive” bat surveys should take place abroad, in the Indochina Peninsula.

“I don’t believe it for a second,” says Hughes, a conservation biologist who’s now at Hong Kong University. Between May 2019 and November 2020, she had done her own survey of 342 bats in the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, a branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in Yunnan province where she worked at the time. As her team reported in Cell in June 2021, it found four viruses related to SARS-CoV-2 in the garden, which is about three times the size of New York City’s Central Park.

More here.

Béla Fleck | Broken Record

Surrealism Versus The Work Ethic

Kaegan Sparks at Artforum:

Ultimately, Surrealist Sabotage presents anti-work aesthetics as a fascinating and enduring thematic in Surrealist production, yet the political stakes of this thematic remain elusive. One reason lies in the book’s tendency toward diffuse and evenhanded treatment of wide-ranging source materials, at times deflecting important nuances and contradictions among and within them. Historical tensions internal to Surrealism are sidelined, including political disagreements between Breton and other interwar Surrealist-communists like Aragon and Bataille (the latter once colorfully denounced Breton’s camp as “too many fucking idealists”). Moreover, the complexities of Soviet art’s evolving orientation toward labor—inextricable, at the time, from the unprecedented challenge of transitioning to a classless society, despite economic underdevelopment and imperialist incursions—are all but elided. Socialist art becomes something of a straw man, reduced to a wholesale celebration of labor for labor’s sake. Nevertheless, Susik succeeds in eliciting tantalizing frictions around the relation of avant-garde movements to leftist politics in her study of the Surrealists’ attempts to “reconcile their revolution of the mind with the Marxist call for a proletarian overthrow.”

Ultimately, Surrealist Sabotage presents anti-work aesthetics as a fascinating and enduring thematic in Surrealist production, yet the political stakes of this thematic remain elusive. One reason lies in the book’s tendency toward diffuse and evenhanded treatment of wide-ranging source materials, at times deflecting important nuances and contradictions among and within them. Historical tensions internal to Surrealism are sidelined, including political disagreements between Breton and other interwar Surrealist-communists like Aragon and Bataille (the latter once colorfully denounced Breton’s camp as “too many fucking idealists”). Moreover, the complexities of Soviet art’s evolving orientation toward labor—inextricable, at the time, from the unprecedented challenge of transitioning to a classless society, despite economic underdevelopment and imperialist incursions—are all but elided. Socialist art becomes something of a straw man, reduced to a wholesale celebration of labor for labor’s sake. Nevertheless, Susik succeeds in eliciting tantalizing frictions around the relation of avant-garde movements to leftist politics in her study of the Surrealists’ attempts to “reconcile their revolution of the mind with the Marxist call for a proletarian overthrow.”

more here.

The Sandstorms in Beijing

Mimi Jiang at the LRB:

As someone from South China who is accustomed to humidity, the first time I went to Beijing I was struck by its dryness, especially in winter. My proximal nail folds cracked, no matter how much hand cream I put on. For Beijing citizens, sandstorms and smog are the twin horrors. One year the sandstorm was so thick it painted the sky orange. Even if you sealed all the windows, the next day your tables and floors would be covered by sand. The spring wind blows it in from the Gobi Desert. The smog, by contrast, has many culprits: fossil fuels, coal, heavy industry, too many cars. The tiny particles hang in the air waiting to be breathed in and no one can escape from it. Even the supreme leader has to breathe the same polluted air as the rest of us. People in Beijing hate the wind for bringing the sand but love it for blowing the smog away.

As someone from South China who is accustomed to humidity, the first time I went to Beijing I was struck by its dryness, especially in winter. My proximal nail folds cracked, no matter how much hand cream I put on. For Beijing citizens, sandstorms and smog are the twin horrors. One year the sandstorm was so thick it painted the sky orange. Even if you sealed all the windows, the next day your tables and floors would be covered by sand. The spring wind blows it in from the Gobi Desert. The smog, by contrast, has many culprits: fossil fuels, coal, heavy industry, too many cars. The tiny particles hang in the air waiting to be breathed in and no one can escape from it. Even the supreme leader has to breathe the same polluted air as the rest of us. People in Beijing hate the wind for bringing the sand but love it for blowing the smog away.

China has been combating desertification for more than four decades. Since 1978 the National Forestry and Grasslands Administration has been planting poplars across a vast area of the Northwest, North and Northeast to hold back the encroaching Gobi.

more here.

My Week With America’s Smartest* People

Eve Peyser in Intelligencer:

In the designated game room at the Nugget Casino Resort in Sparks, Nevada, which was open 24 hours a day during this year’s Mensa Annual Gathering, I sat at a table with a woman named Kimberly Bakke, a 30-year-old purple-haired pastry chef and teacher from Las Vegas. Bakke is basically Mensa royalty. A 1996 Orange County Register article about her admission to the high-IQ club revealed that she was conceived at a Mensa convention, and she hasn’t missed one since; she became a member when she was three. “I have a big brain,” she told the Register reporter, who noted that her IQ was 143, about 50 points higher than the average among people of all ages. Bakke was hanging out with Christopher Whalen, a 35-year-old defense contractor from Omaha, Nebraska, who was admitted to the club in 2016. They met in a Mensa Gen-Y Facebook group shortly after, and became fast friends, texting each other every day. The 2022 Annual Gathering (AG, as Mensans call it) was Whalen’s first and marked the first time the pair met IRL.

In the designated game room at the Nugget Casino Resort in Sparks, Nevada, which was open 24 hours a day during this year’s Mensa Annual Gathering, I sat at a table with a woman named Kimberly Bakke, a 30-year-old purple-haired pastry chef and teacher from Las Vegas. Bakke is basically Mensa royalty. A 1996 Orange County Register article about her admission to the high-IQ club revealed that she was conceived at a Mensa convention, and she hasn’t missed one since; she became a member when she was three. “I have a big brain,” she told the Register reporter, who noted that her IQ was 143, about 50 points higher than the average among people of all ages. Bakke was hanging out with Christopher Whalen, a 35-year-old defense contractor from Omaha, Nebraska, who was admitted to the club in 2016. They met in a Mensa Gen-Y Facebook group shortly after, and became fast friends, texting each other every day. The 2022 Annual Gathering (AG, as Mensans call it) was Whalen’s first and marked the first time the pair met IRL.

More here.

Friday Poem

Here are two quatrains by two famous Urdu poets – Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Sahir Ludhianvi – who have opposing views of a beloved’s memory. They were contemporaries, though Faiz was about ten years older. Faiz lived and wrote in Pakistan and was a member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement. He was a Communist and was thrown in prison for that reason. Sahir lived and wrote mostly in India, though for a brief period he was in Lahore and fled that place for India when, he too, was accused of being a communist. He was also a member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement. Both wrote eloquently and passionately. There the similarities end. Faiz wrote of love with optimism and hope – he was going to be successful in love. Sahir wrote in gloomy terms and with a sense of self-pity – love was not all roses for him.

In these two, very famous quatrains of theirs, one can see the difference between them. Faiz sees the lost memory of a beloved as a soothing breeze, as an onset of growth, as a balm to his fevered brow; Sahir saw love as happiness quickly leading to grief, as a flower whose thorns would beset him, soon. —Translator’s Note

___________________________________

Faiz Ahmed Faiz:

Last Night Your Lost Memory

Last night your lost memory crept into my heart

As in a wasteland, spring blossoms quietly

As in a desert, the zephyr sways gently

As to a dying man, relief comes, unexpectedly.

………………………… §§§

Raat yun dil mein teri, khoyi hui yaad aayi

Raat yun dil mein teri, khoyi hui yaad aayi

Jaise viraane mein chupke se bahaar aa jaye

Jaise sahraon mein haule se chale baad-ae-naseem

Jaise bimaar ko be-wajaah quraar aa jaaye

………………………… §§§

Sahir Ludhianvi

I picked a few flowers of happiness

I picked a few flowers of happiness

And for ages I was sunk in grief

Meeting you brings me happiness, yet

After meeting you, I remain in grief

………………………… §§§

Chand kaliyāñ nashāt kī chun kar

chand kaliyāñ nashāt kī chun kar

muddatoñ mahv-e-yās rahtā huuñ

terā milnā ḳhushī kī baat sahī

tujh se mil kar udaas rahtā huuñ

………………………… §§§

Translations by Ajit Dutta

Thursday, August 18, 2022

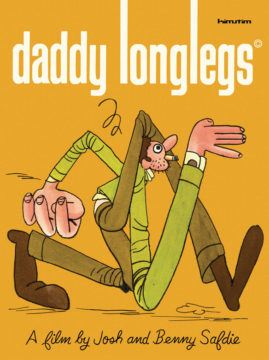

Daddy Longlegs: Presto Magic!

Stéphane Delorme at The Current:

Daddy Longlegs (2009) is the triumphant culmination of the Safdie brothers’ early period. By the time the two young prodigies (twenty-four and twenty-two years old) joined forces to make a movie about their childhood memories of their father, Josh and Benny had directed several short films under the aegis of their filmmaking collective, Red Bucket Films. Josh had also completed a seventy-minute feature, The Pleasure of Being Robbed (2008). Benny was drawn to slapstick and tangible reality, while Josh was more romantic and given to flights of fancy. Taken together, the Safdie touch is a fragmentary art of wonder: a tireless enthusiasm for the wonders of the world, which the filmmakers respond to with constant inventiveness. Imagination and realism go hand in hand, just as the two brothers move through life, guided by their skill at catalyzing the magic of the moment (“Presto magic!” to quote Lenny Sokol, the father in Daddy Longlegs, speaking like a conjurer). With their first feature as a duo, the brothers continued the lo-fi methods they had developed in their shorts, shooting clandestinely with a group of friends, moving the camera as frantically as their characters moved, and interspersing majestic anti-folk tunes to make us laugh and cry.

Daddy Longlegs (2009) is the triumphant culmination of the Safdie brothers’ early period. By the time the two young prodigies (twenty-four and twenty-two years old) joined forces to make a movie about their childhood memories of their father, Josh and Benny had directed several short films under the aegis of their filmmaking collective, Red Bucket Films. Josh had also completed a seventy-minute feature, The Pleasure of Being Robbed (2008). Benny was drawn to slapstick and tangible reality, while Josh was more romantic and given to flights of fancy. Taken together, the Safdie touch is a fragmentary art of wonder: a tireless enthusiasm for the wonders of the world, which the filmmakers respond to with constant inventiveness. Imagination and realism go hand in hand, just as the two brothers move through life, guided by their skill at catalyzing the magic of the moment (“Presto magic!” to quote Lenny Sokol, the father in Daddy Longlegs, speaking like a conjurer). With their first feature as a duo, the brothers continued the lo-fi methods they had developed in their shorts, shooting clandestinely with a group of friends, moving the camera as frantically as their characters moved, and interspersing majestic anti-folk tunes to make us laugh and cry.

more here.

Lessons Through Surrealism

Becky Y. Lu at Hudson Review:

Surrealism is having a moment. It is the theme of this year’s Venice Biennale and was that of last winter’s major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Absurdist, dystopic shows like Severance (Apple TV+) and Russian Doll (Netflix) are resonating with audiences and critics. René Magritte’s L’empire des lumières (1961) fetched a record price recently at auction. And why not, for we are besieged by surrealities, both serious and comical, almost daily: the potential resurgence of underground abortions in the U.S., Will Smith slapping Chris Rock at the Oscars, Russia’s continued assault of Ukraine, the histrionics of Elon Musk’s flailing Twitter takeover, senseless deaths from unnecessary guns, Partygate at 10 Downing Street, the airlifting of infant formula into the richest country in history, the rise of autocracy, and so on. The chaos that crowds our newsfeeds seems to belong to another century, if not an alternate universe.

Surrealism is having a moment. It is the theme of this year’s Venice Biennale and was that of last winter’s major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Absurdist, dystopic shows like Severance (Apple TV+) and Russian Doll (Netflix) are resonating with audiences and critics. René Magritte’s L’empire des lumières (1961) fetched a record price recently at auction. And why not, for we are besieged by surrealities, both serious and comical, almost daily: the potential resurgence of underground abortions in the U.S., Will Smith slapping Chris Rock at the Oscars, Russia’s continued assault of Ukraine, the histrionics of Elon Musk’s flailing Twitter takeover, senseless deaths from unnecessary guns, Partygate at 10 Downing Street, the airlifting of infant formula into the richest country in history, the rise of autocracy, and so on. The chaos that crowds our newsfeeds seems to belong to another century, if not an alternate universe.

It was perhaps no coincidence, then, that the Metropolitan Opera revived Jonathan Miller’s Surrealist, fin-de-siècle take on Igor Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress.

more here.

The Rake’s Progress: “As I Was Saying, Both Brothers Wore Moustaches”

Thursday Poem

Piute Creek

One granite ridge

A tree, would be enough

Or even a rock, a small creek,

A bark shred in a pool.

Hill beyond hill, folded and twisted

Tough trees crammed

In thin stone fractures

A huge moon on it all, is too much.

The mind wanders. A million

Summers, night air still and the rocks

Warm. Sky over endless mountains.

All the junk that goes with being human

Drops away, hard rock wavers

Even the heavy present seems to fail

This bubble of a heart.

Words and books

like a small creek off a high ledge

Gone in the dry air.

A clear, attentive mind

Has no meaning but that

Which sees is truly seen.

No one loves rock, yet we are here.

Night chills. A flick

In the moonlight

Slips into juniper shadow:

Back there unseen

Cold proud eyes

Of cougar or coyote

Watch me rise and go.

by Gary Snyder

from Naked Poetry

Bobbs-Merril Company, 1969

The importance of nothing

Jeremy Webb in Delancey Place:

“We have heard that when it arrived in Europe, zero was treated with suspicion. We don’t think of the absence of sound as a type of sound, so why should the absence of numbers be a number, argued its detractors. It took centuries for zero to gain acceptance. It is certainly not like other numbers. To work with it requires some tough intellectual contortions, as mathematician Ian Stewart explains.

“We have heard that when it arrived in Europe, zero was treated with suspicion. We don’t think of the absence of sound as a type of sound, so why should the absence of numbers be a number, argued its detractors. It took centuries for zero to gain acceptance. It is certainly not like other numbers. To work with it requires some tough intellectual contortions, as mathematician Ian Stewart explains.

“Nothing is more interesting than nothing, nothing is more puzzling than nothing, and nothing is more important than nothing. For mathematicians, nothing is one of their favorite topics, a veritable Pandora’s box of curiosities and paradoxes. What lies at the heart of mathematics? You guessed it: nothing.

“Word games like this are almost irresistible when you talk about nothing, but in the case of math this is cheating slightly. What lies at the heart of math is related to nothing, but isn’t quite the same thing. ‘Nothing’ is well, nothing. A void. Total absence of thingness. Zero, however, is definitely a thing. It is a number. It is, in fact, the number you get when you count your oranges and you haven’t got any. And zero has caused mathematicians more heartache, and given them more joy, than any other number.

“Zero, as a symbol, is part of the wonderful invention of ‘place notation.’ Early notations for numbers were weird and wonderful, a good example being Roman numerals, in which the number 1,998 comes out as MCMXCVIII one thousand (M) plus one hundred less than a thousand (CM) plus ten less than a hundred (XC) plus five (V) plus one plus one plus one (III). Try doing arithmetic with that lot. So the symbols were used to record numbers, while calculations were done using the abacus, piling up stones in rows in the sand or moving beads on wires.

More here.