Dylan Matthews in Vox:

“The 140 years from 1870 to 2010 of the long twentieth century were, I strongly believe, the most consequential years of all humanity’s centuries.” So argues Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, the new magnum opus from UC Berkeley professor Brad DeLong. It’s a bold claim. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years; the “long twentieth century” represents 0.05 percent of that history.

“The 140 years from 1870 to 2010 of the long twentieth century were, I strongly believe, the most consequential years of all humanity’s centuries.” So argues Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, the new magnum opus from UC Berkeley professor Brad DeLong. It’s a bold claim. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years; the “long twentieth century” represents 0.05 percent of that history.

But to DeLong, who beyond his academic work is known for his widely read blog on economics, something incredible happened in that sliver of time that eluded our species for the other 99.95 percent of our history. Whereas before 1870, technological progress proceeded slowly, if at all, after 1870 it accelerated dramatically. And especially for residents of rich countries, this technological progress brought a world of unprecedented plenty. DeLong reports that in 1870, an average unskilled male worker living in London could afford 5,000 calories for himself and his family on his daily wages. That was more than the 3,000 calories he could’ve afforded in 1600, a 66 percent increase — progress, to be sure. But by 2010, the same worker could afford 2.4 million calories a day, a nearly five hundred fold increase.

More here.

Over the past five years, I have studied the phenomenon of what I call “political overconfidence.” My work, in tandem with other researchers’ studies, reveals the ways it thwarts democratic politics.

Over the past five years, I have studied the phenomenon of what I call “political overconfidence.” My work, in tandem with other researchers’ studies, reveals the ways it thwarts democratic politics. Gorbachev was born in 1931, on the other side of the revolutionary chasm. Though famine and terror made their appearances in his childhood, he entered adulthood after the most traumatic periods of Soviet history had already passed. Graduating from university two years after Stalin’s death, Gorbachev became part of a generation of starry-eyed young utopians. As their elders began to make their peace with the indefinite deferral of communism, young people were determined to see it in their lifetimes. In 1967, a group of youth in the city of Novorossiisk sank a time capsule into the Black Sea filled with letters addressed to the anticipated space-faring communist future of 2017. A schoolgirl named Olga wrote, “We dream of communism, of a time when you can eat ice cream and go to the movies for free, when machines will do our homework while our teachers will be patient robots. You live under communism, and I will live under communism too, with the only difference being that you will be as old as I was fifty years ago.” Gorbachev, on the older end of this generation, was then just beginning his rapid political ascent in the nearby city of Stavropol.

Gorbachev was born in 1931, on the other side of the revolutionary chasm. Though famine and terror made their appearances in his childhood, he entered adulthood after the most traumatic periods of Soviet history had already passed. Graduating from university two years after Stalin’s death, Gorbachev became part of a generation of starry-eyed young utopians. As their elders began to make their peace with the indefinite deferral of communism, young people were determined to see it in their lifetimes. In 1967, a group of youth in the city of Novorossiisk sank a time capsule into the Black Sea filled with letters addressed to the anticipated space-faring communist future of 2017. A schoolgirl named Olga wrote, “We dream of communism, of a time when you can eat ice cream and go to the movies for free, when machines will do our homework while our teachers will be patient robots. You live under communism, and I will live under communism too, with the only difference being that you will be as old as I was fifty years ago.” Gorbachev, on the older end of this generation, was then just beginning his rapid political ascent in the nearby city of Stavropol. T

T Democracy is the worst form of government,”

Democracy is the worst form of government,”  Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new

Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new  Unlike most modern European languages, English designates book-length works of prose fiction with the term “novel”. Imported sometime in the mid-16th century from Italy – where novella had been coined to describe the short stories collected in Boccaccio’s Decameron 200 years before – and extended to its more or less current sense in the 17th century, the word retains a semantic filiation to that other child of the age of print, the newspaper, and thus to the concepts of information and modernity itself. Until the Austenite revolution of 1811 the novel often cloaked itself in the trappings of genres later classified as

Unlike most modern European languages, English designates book-length works of prose fiction with the term “novel”. Imported sometime in the mid-16th century from Italy – where novella had been coined to describe the short stories collected in Boccaccio’s Decameron 200 years before – and extended to its more or less current sense in the 17th century, the word retains a semantic filiation to that other child of the age of print, the newspaper, and thus to the concepts of information and modernity itself. Until the Austenite revolution of 1811 the novel often cloaked itself in the trappings of genres later classified as  An artificial intelligence model built by Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Eye and Ear scientists was shown to be significantly more accurate than doctors at diagnosing pediatric ear infections in the first head-to-head evaluation of its kind, the research team working to develop the model for clinical use reported.

An artificial intelligence model built by Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Eye and Ear scientists was shown to be significantly more accurate than doctors at diagnosing pediatric ear infections in the first head-to-head evaluation of its kind, the research team working to develop the model for clinical use reported. A sizable literature tracing back to Richard Hofstadter’s The Paranoid Style (1964) argues that Republicans and conservatives are more likely to believe conspiracy theories than Democrats and liberals. However, the evidence for this proposition is mixed. Since conspiracy theory beliefs are associated with dangerous orientations and behaviors, it is imperative that social scientists better understand the connection between conspiracy theories and political orientations. Employing 20 surveys of Americans from 2012 to 2021 (total n = 37,776), as well as surveys of 20 additional countries spanning six continents (total n = 26,416), we undertake an expansive investigation of the asymmetry thesis. First, we examine the relationship between beliefs in 52 conspiracy theories and both partisanship and ideology in the U.S.; this analysis is buttressed by an examination of beliefs in 11 conspiracy theories across 20 more countries. In our second test, we hold constant the content of the conspiracy theories investigated—manipulating only the partisanship of the theorized villains—to decipher whether those on the left or right are more likely to accuse political out-groups of conspiring. Finally, we inspect correlations between political orientations and the general predisposition to believe in conspiracy theories over the span of a decade.

A sizable literature tracing back to Richard Hofstadter’s The Paranoid Style (1964) argues that Republicans and conservatives are more likely to believe conspiracy theories than Democrats and liberals. However, the evidence for this proposition is mixed. Since conspiracy theory beliefs are associated with dangerous orientations and behaviors, it is imperative that social scientists better understand the connection between conspiracy theories and political orientations. Employing 20 surveys of Americans from 2012 to 2021 (total n = 37,776), as well as surveys of 20 additional countries spanning six continents (total n = 26,416), we undertake an expansive investigation of the asymmetry thesis. First, we examine the relationship between beliefs in 52 conspiracy theories and both partisanship and ideology in the U.S.; this analysis is buttressed by an examination of beliefs in 11 conspiracy theories across 20 more countries. In our second test, we hold constant the content of the conspiracy theories investigated—manipulating only the partisanship of the theorized villains—to decipher whether those on the left or right are more likely to accuse political out-groups of conspiring. Finally, we inspect correlations between political orientations and the general predisposition to believe in conspiracy theories over the span of a decade. PRESIDENT LAWRENCE S. BACOW

PRESIDENT LAWRENCE S. BACOW Terri Apter, a psychologist, still remembers the time she explained to an 18-year-old how the teenage brain works: “So that’s why I feel like my head’s exploding!” the teen replied, with pleasure. Parents and teachers of teens may recognise that sensation of dealing with a highly combustible mind. The teenage years can feel like a shocking transformation – a turning inside out of the mind and soul that renders the person unrecognisable from the child they once were. There’s the hard-to-control mood swings, identity crises and the hunger for social approval, a newfound taste for risk and adventure, and a seemingly complete inability to think about the future repercussions of their actions.

Terri Apter, a psychologist, still remembers the time she explained to an 18-year-old how the teenage brain works: “So that’s why I feel like my head’s exploding!” the teen replied, with pleasure. Parents and teachers of teens may recognise that sensation of dealing with a highly combustible mind. The teenage years can feel like a shocking transformation – a turning inside out of the mind and soul that renders the person unrecognisable from the child they once were. There’s the hard-to-control mood swings, identity crises and the hunger for social approval, a newfound taste for risk and adventure, and a seemingly complete inability to think about the future repercussions of their actions. Dostoevsky’s own fixation on Lacenaire and his crime, which he declared “more exciting than all possible fiction,” is the focus of Birmingham’s consistently immersing The Sinner and the Saint. The Lacenaire who emerges from these pages is a subtle, ambiguous, sometimes insidiously appealing challenger to a corrupt established order. “I come to preach the religion of fear to the elite,” he announced at his trial, sounding a bit like a prototype Charles Manson. Almost anyone could write a gripping account of Lacenaire’s particular offense, but it took a writer of Dostoevsky’s gifts, not to mention of his experience in Semyonovosky Square, to painstakingly lead his readers on a course between the extremes of revulsion and fascination. What really interested Dostoevsky, and interests us, is the morality of crime, and how people can come to rationalize even the most depraved homicidal frenzy. He’s an author who takes risks, makes us both laugh and wince, and (depending on the translator’s art) writes like an angel with a devilish sense of humor.

Dostoevsky’s own fixation on Lacenaire and his crime, which he declared “more exciting than all possible fiction,” is the focus of Birmingham’s consistently immersing The Sinner and the Saint. The Lacenaire who emerges from these pages is a subtle, ambiguous, sometimes insidiously appealing challenger to a corrupt established order. “I come to preach the religion of fear to the elite,” he announced at his trial, sounding a bit like a prototype Charles Manson. Almost anyone could write a gripping account of Lacenaire’s particular offense, but it took a writer of Dostoevsky’s gifts, not to mention of his experience in Semyonovosky Square, to painstakingly lead his readers on a course between the extremes of revulsion and fascination. What really interested Dostoevsky, and interests us, is the morality of crime, and how people can come to rationalize even the most depraved homicidal frenzy. He’s an author who takes risks, makes us both laugh and wince, and (depending on the translator’s art) writes like an angel with a devilish sense of humor. I did not expect that studying a childhood discipline would lead me to wonder about divine matters, but the possibility of a divine entity is threaded throughout mathematics, which, in its essence, so far as I can tell, is a mystical pursuit, an attempt to claim territory and define objects seen only in the minds of people doing mathematics. Why do I care about abstract possibilities and especially about God, when I have no idea what such a thing might be? A concept? An actual entity? Something hidden but accessible, or forever out of reach? Something once present and now gone? Something that ancient people appear to have experienced at close hand?

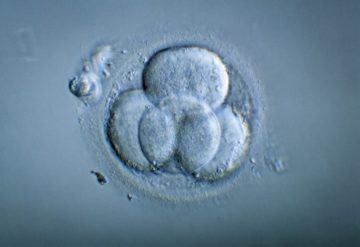

I did not expect that studying a childhood discipline would lead me to wonder about divine matters, but the possibility of a divine entity is threaded throughout mathematics, which, in its essence, so far as I can tell, is a mystical pursuit, an attempt to claim territory and define objects seen only in the minds of people doing mathematics. Why do I care about abstract possibilities and especially about God, when I have no idea what such a thing might be? A concept? An actual entity? Something hidden but accessible, or forever out of reach? Something once present and now gone? Something that ancient people appear to have experienced at close hand? When the first baby to be conceived using a technique that mixes genetic material from three people

When the first baby to be conceived using a technique that mixes genetic material from three people