Marie Vodicka in Science:

Through a series of vignettes peppered with illustrative analogies and vibrant characters, Siddhartha Mukherjee invites readers of his new book, The Song of the Cell, on a tour of cell biology from its early origins to its present and future applications. Mukherjee is clear from the start that the book is not a comprehensive history of the field but rather a meandering journey through selected seminal scientific discoveries. The book’s conversational style draws the reader in, and the text is enlivened by descriptions of major players in the field. We learn, for example, that Frederick Banting—co-winner of the Nobel Prize for the discovery of insulin—devised his key experiment only after experiencing financial difficulties in his medical practice, a broken-down car, and a sleepless night puzzling over a recently published journal article.

Through a series of vignettes peppered with illustrative analogies and vibrant characters, Siddhartha Mukherjee invites readers of his new book, The Song of the Cell, on a tour of cell biology from its early origins to its present and future applications. Mukherjee is clear from the start that the book is not a comprehensive history of the field but rather a meandering journey through selected seminal scientific discoveries. The book’s conversational style draws the reader in, and the text is enlivened by descriptions of major players in the field. We learn, for example, that Frederick Banting—co-winner of the Nobel Prize for the discovery of insulin—devised his key experiment only after experiencing financial difficulties in his medical practice, a broken-down car, and a sleepless night puzzling over a recently published journal article.

While practitioners of biology will recognize many in this cast of characters, from historical icons to cameos by peers and contemporaries, the book’s individual and idiosyncratic descriptions of the scientists and their discoveries are both a strength and a weakness. Such a strategy can help to keep readers engaged, but it can also perpetuate the inaccurate notion of science as a solitary activity, sparked by individual genius.

More here.

I

I Inez Holden’s diary – a mammoth undertaking, only fragments of which have ever escaped into print – carries a rueful little entry from August 1948. “I read Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh,” the diarist writes. But the tale of Charles Ryder’s dealings with the tantalising progeny of the Marquess of Marchmain, here in an unfallen world of Oxford quadrangles and stately pleasure domes, awakens a feeling of “nostalgic depression”. This, Holden decides, is simply another of “those stories of High Life of the Twenties which everyone seemed to have enjoyed but I never did”.

Inez Holden’s diary – a mammoth undertaking, only fragments of which have ever escaped into print – carries a rueful little entry from August 1948. “I read Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh,” the diarist writes. But the tale of Charles Ryder’s dealings with the tantalising progeny of the Marquess of Marchmain, here in an unfallen world of Oxford quadrangles and stately pleasure domes, awakens a feeling of “nostalgic depression”. This, Holden decides, is simply another of “those stories of High Life of the Twenties which everyone seemed to have enjoyed but I never did”. There are many complex theories about the nature and function of art; I am going to propose a very simple one. My simple theory is also broad: it applies to narrative fiction broadly conceived, from epic poems to Greek tragedies to Shakespearean comedies to short stories to movies. It also applies to most pop songs, many lyric poems and some—though far from most—paintings, photographs and sculptures. My theory is that art is for seeing evil.

There are many complex theories about the nature and function of art; I am going to propose a very simple one. My simple theory is also broad: it applies to narrative fiction broadly conceived, from epic poems to Greek tragedies to Shakespearean comedies to short stories to movies. It also applies to most pop songs, many lyric poems and some—though far from most—paintings, photographs and sculptures. My theory is that art is for seeing evil. T

T A

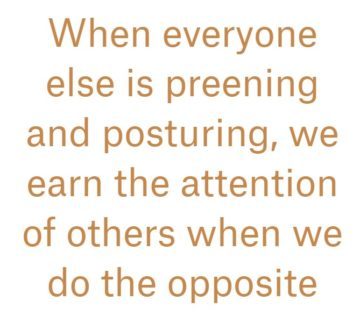

A Speaking broadly, Leibniz’s rules fall into three basic categories: advice on how to communicate with others, advice on how to carry oneself with others, and advice on the sorts of subjects one ought to study. On the first front, Leibniz argues that effective communication requires us to engage our audience’s attention in such a way that others will feel connected to and included in our conversation. In this vein, we’re told that ‘small commonplaces’ that ‘can be told or recounted with flair’ get noticed. Later, we’re told we ought to ‘intermix some charm into business negotiations and meetings’, and that, in more casual conversations, we should make sure to give openings so that ‘every person recounts something’ and has an opportunity to speak their mind. The lesson here is that when we speak with others, we should ‘work to bring new things up’ in such a way that others are ‘drawn into conversation’.

Speaking broadly, Leibniz’s rules fall into three basic categories: advice on how to communicate with others, advice on how to carry oneself with others, and advice on the sorts of subjects one ought to study. On the first front, Leibniz argues that effective communication requires us to engage our audience’s attention in such a way that others will feel connected to and included in our conversation. In this vein, we’re told that ‘small commonplaces’ that ‘can be told or recounted with flair’ get noticed. Later, we’re told we ought to ‘intermix some charm into business negotiations and meetings’, and that, in more casual conversations, we should make sure to give openings so that ‘every person recounts something’ and has an opportunity to speak their mind. The lesson here is that when we speak with others, we should ‘work to bring new things up’ in such a way that others are ‘drawn into conversation’. In policy circles, discussions about artificial intelligence invariably pit China against the United States in a race for technological supremacy. If the key resource is data, then China, with its billion-plus citizens and lax protections against state surveillance, seems destined to win. Kai-Fu Lee, a famous computer scientist, has claimed that data is the new oil, and China the new OPEC. If superior technology is what provides the edge, however, then the United States, with its world class university system and talented workforce, still has a chance to come out ahead. For either country, pundits assume that superiority in AI will lead naturally to broader economic and military superiority.

In policy circles, discussions about artificial intelligence invariably pit China against the United States in a race for technological supremacy. If the key resource is data, then China, with its billion-plus citizens and lax protections against state surveillance, seems destined to win. Kai-Fu Lee, a famous computer scientist, has claimed that data is the new oil, and China the new OPEC. If superior technology is what provides the edge, however, then the United States, with its world class university system and talented workforce, still has a chance to come out ahead. For either country, pundits assume that superiority in AI will lead naturally to broader economic and military superiority. Pakistan has two things: very high mountains, and a very flat plain.

Pakistan has two things: very high mountains, and a very flat plain. One of the major challenges of space travel is that there are no ready-made resources there. Mars, for example, has no food, shelter, oxygen, fuel, or power. It likely has water, but it’s not certain how much and how accessible. So for now any human mission to Mars will have to bring all recourses from Earth. Getting stuff to Mars is massively expensive, and resupply can take 6-9 months, during optimal launch windows. Keeping humans alive on Mars for any length of time is therefore a very tenuous and expensive endeavor.

One of the major challenges of space travel is that there are no ready-made resources there. Mars, for example, has no food, shelter, oxygen, fuel, or power. It likely has water, but it’s not certain how much and how accessible. So for now any human mission to Mars will have to bring all recourses from Earth. Getting stuff to Mars is massively expensive, and resupply can take 6-9 months, during optimal launch windows. Keeping humans alive on Mars for any length of time is therefore a very tenuous and expensive endeavor. If all the criminal investigations into former President Donald Trump end in conviction, then Trump will be a true renaissance man of crime.

If all the criminal investigations into former President Donald Trump end in conviction, then Trump will be a true renaissance man of crime. If the point of publishing a book is to have a public relations campaign, Will MacAskill is the greatest English writer since Shakespeare. He and his book

If the point of publishing a book is to have a public relations campaign, Will MacAskill is the greatest English writer since Shakespeare. He and his book  When considering environmental issues, the usual rallying cry is that of “saving the planet”. Rarely do people acknowledge that, rather, it is us who need saving from ourselves. We have appropriated ever-larger parts of Earth for our use while trying to separate ourselves from it, ensconced in cities. But we cannot keep the forces of life at bay forever. In A Natural History of the Future, ecologist and evolutionary biologist Rob Dunn considers some of the rules and laws that underlie biology to ask what is in store for us as a species, and how we might survive without destroying the very fabric on which we depend.

When considering environmental issues, the usual rallying cry is that of “saving the planet”. Rarely do people acknowledge that, rather, it is us who need saving from ourselves. We have appropriated ever-larger parts of Earth for our use while trying to separate ourselves from it, ensconced in cities. But we cannot keep the forces of life at bay forever. In A Natural History of the Future, ecologist and evolutionary biologist Rob Dunn considers some of the rules and laws that underlie biology to ask what is in store for us as a species, and how we might survive without destroying the very fabric on which we depend. Mikhail S. Gorbachev, whose rise to power in the Soviet Union set in motion a series of revolutionary changes that transformed the map of Europe and ended the Cold War that had threatened the world with nuclear annihilation, has died in Moscow. He was 91.

Mikhail S. Gorbachev, whose rise to power in the Soviet Union set in motion a series of revolutionary changes that transformed the map of Europe and ended the Cold War that had threatened the world with nuclear annihilation, has died in Moscow. He was 91.