by Andrew Bard Schmookler

Evil: Lost and Found

Evil: Lost and Found

Over the centuries, for people whose worldview was governed by the religions of Western civilization, it was reasonably straightforward to conceive of the existence of a “Force of Evil.” Judeo-Christian religion personified such a force in the figure of Satan, or the Devil.

The image of this Supernatural Being enabled people to form some intuitive conception of a powerful force that makes bad things happen: the Devil, with malevolent intent, was always working to get people to do what they shouldn’t do, and to degrade the human world generally.

Wielding his powers with diabolical cleverness, the Devil could make the world uglier. (Quoth Luther: “For still our ancient foe / Doth seek to work us woe;/ His craft and power are great/ And, armed with cruel hate./ On earth is not his equal.”)

The more recent historical emergence of a secular worldview has meant that — in the minds of a major component of the Western world — this supernatural figure has disappeared from people’s picture of what’s real in our world, with nothing equivalent to take its place. And this disappearance of Satan left most of those people with no way of conceiving the possibility of anything existing that might reasonably be called a “Force of Evil.” Read more »

Some words are much more frequent than others. For example, in a sample of almost

Some words are much more frequent than others. For example, in a sample of almost  More than 500,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans were migrating around the world when a fateful genetic mutation caused some of their brains to suddenly improve. This mutation, researchers report in Science

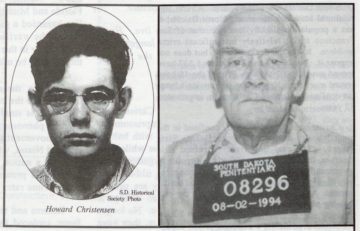

More than 500,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans were migrating around the world when a fateful genetic mutation caused some of their brains to suddenly improve. This mutation, researchers report in Science In September of 1994, the editors and writers of The Angolite sought to identify everyone in America who had served two decades or more in prison in a piece titled, “

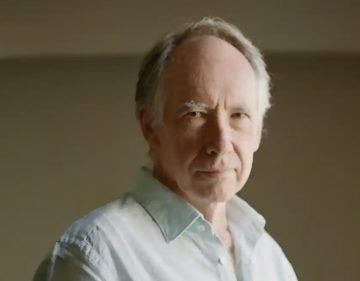

In September of 1994, the editors and writers of The Angolite sought to identify everyone in America who had served two decades or more in prison in a piece titled, “ Although not originally part of the notorious gang of writers – Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and the late Christopher Hitchens – who made their names in the 70s and dominated the literary scene for much longer (too long, according to their critics), Rushdie arrived a few years later with the publication in 1981 of

Although not originally part of the notorious gang of writers – Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and the late Christopher Hitchens – who made their names in the 70s and dominated the literary scene for much longer (too long, according to their critics), Rushdie arrived a few years later with the publication in 1981 of  Statesman, majored in women’s studies. During her university years, she believed that hookup culture, pornography, and rough sex were all OK for consenting adults. A decade later, she’s changed her mind. Ms. Perry’s experience of working at a rape crisis center made her question the narrative she’d been taught that “rape is about power, not sex.” She then began to rethink other tenets of second-wave academic feminism.

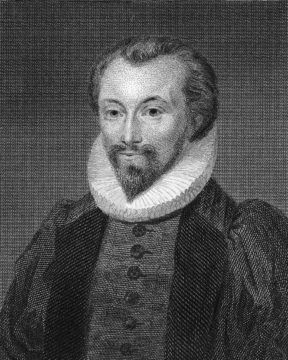

Statesman, majored in women’s studies. During her university years, she believed that hookup culture, pornography, and rough sex were all OK for consenting adults. A decade later, she’s changed her mind. Ms. Perry’s experience of working at a rape crisis center made her question the narrative she’d been taught that “rape is about power, not sex.” She then began to rethink other tenets of second-wave academic feminism. The power of John Donne’s words nearly killed a man.

The power of John Donne’s words nearly killed a man.

Chris Lehmann in The Baffler:

Chris Lehmann in The Baffler: Catarina Dutilh Novaes and Silvia Ivani in Boston Review:

Catarina Dutilh Novaes and Silvia Ivani in Boston Review: F

F Camila Vergara in Sidecar:

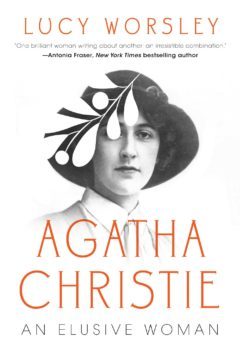

Camila Vergara in Sidecar: Agatha Christie’s best books have crisp dialogue and high-velocity plots. The bad ones have a Mad Libs quality: feeble prose studded with blank spots into which you can picture the prolific Christie plugging a random “BODY PART” or “WEAPON.” In a 1971 study of English crime fiction, Colin Watson snickered that Christie “seems to have been well aware that intelligence and readership-potential are quite unrelated.”

Agatha Christie’s best books have crisp dialogue and high-velocity plots. The bad ones have a Mad Libs quality: feeble prose studded with blank spots into which you can picture the prolific Christie plugging a random “BODY PART” or “WEAPON.” In a 1971 study of English crime fiction, Colin Watson snickered that Christie “seems to have been well aware that intelligence and readership-potential are quite unrelated.” For as long as she can remember, Kay Tye has wondered why she feels the way she does. Rather than just dabble in theories of the mind, however, Tye has long wanted to know what was happening in the brain. In college in the early 2000s, she could not find a class that spelled out how electrical impulses coursing through the brain’s trillions of connections could

For as long as she can remember, Kay Tye has wondered why she feels the way she does. Rather than just dabble in theories of the mind, however, Tye has long wanted to know what was happening in the brain. In college in the early 2000s, she could not find a class that spelled out how electrical impulses coursing through the brain’s trillions of connections could