Gardiner Means in Phenomenal World:

Gardiner Means in Phenomenal World:

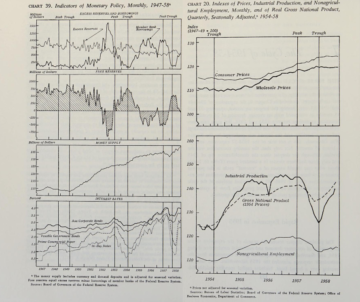

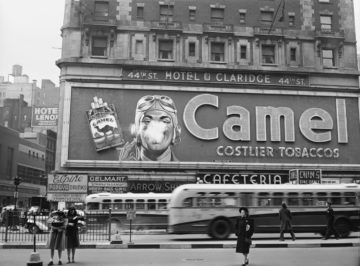

If they are remembered at all, the 1950s are now thought of as a lost golden age of stable growth and political economic consensus. But the second half of the decade saw rising prices, tightening financial conditions, diminished industrial employment, and stagnant investment. With knowledge of the turbulence that followed, historians have increasingly interpreted the economic history of the late 1950s not as a minor aberration to a stable political order but as revealing structural pathologies latent in the twentieth-century industrial economy. If contemporaries did not yet use the word “stagflation,” they might as well have, referring to the decade’s rising prices with terms such as “new inflation” and “recession-cum-inflation.”

Gardiner C. Means was one of the most astute analysts of the policy dilemma created by this anti-inflationary monetary policy. Means owed his original prominence to The Modern Corporation and Private Property, which he co-authored with Adolf Berle in 1932. This surprise best-seller popularized the idea that corporate capitalism—specifically, its tendency to separate ownership and management—represented a radical transformation in social organization. The book placed the question of corporate power on the agenda at the depths of the Great Depression, and Means parlayed this commercial and intellectual success into a position at the Department of Agriculture in the first Franklin Roosevelt administration. The New Deal’s response to that conjuncture was in part shaped by his distinctive analysis: the length and depth of the 1930s recession was, he argued, a consequence of an imbalance in relative prices between economic sectors—a diagnosis which prescribed national economic planning to raise agricultural prices and allow farmers to afford an expanded volume of industrial production.

Twenty-five years later, Means brought his familiarity with corporate pricing patterns to the distinctive problem of the postwar economy.

More here.

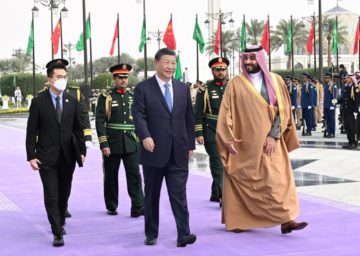

Pranab Bardhan in Boston Review:

Pranab Bardhan in Boston Review: Susan Neiman in Unherd:

Susan Neiman in Unherd: Malcom Kyeyune in Compact Magazine:

Malcom Kyeyune in Compact Magazine: O

O “

“ Tompkins produced two fine books in the 1990s, “West of Everything” and “A Life in School,” but she more or less retired after that — until now, re-emerging with another impassioned missive that concerns itself with shadows and dualities and the self. “Reading Through the Night” is a perfect book for anyone who believes literature should amount to more than diversion and fodder for term papers. The recent trend in better writing about reading generally falls into two camps: books that tell the story of a writer’s relationship with another writer, and books that chronicle one’s reading life. Tompkins does both.

Tompkins produced two fine books in the 1990s, “West of Everything” and “A Life in School,” but she more or less retired after that — until now, re-emerging with another impassioned missive that concerns itself with shadows and dualities and the self. “Reading Through the Night” is a perfect book for anyone who believes literature should amount to more than diversion and fodder for term papers. The recent trend in better writing about reading generally falls into two camps: books that tell the story of a writer’s relationship with another writer, and books that chronicle one’s reading life. Tompkins does both. In every argument, debate or article about the rise of the modern celebrity, one name always reappears:

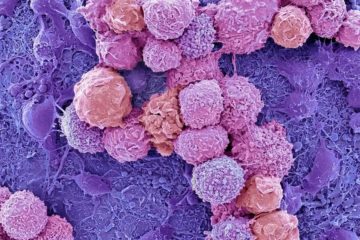

In every argument, debate or article about the rise of the modern celebrity, one name always reappears:  Balls of human brain cells grown in a dish, known as

Balls of human brain cells grown in a dish, known as  “Those in the 1 percent are walking off with the riches, but in doing so they have provided nothing but anxiety and insecurity to the 99 percent,” explained Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz in his 2012 book The Price of Inequality. The “main fault line in the American society is . . . between the 1 percent and everybody else,” insisted celebrated economists Emanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman in their book The Triumph of Injustice, published amid the 2020 presidential campaign. Dramatic wealth tax proposals by Democratic presidential candidates Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, chair of the tax-writing committee Senator Ron Wyden, and even an income taxation plan by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez do not come close to hiking taxes on anyone below the 1 percent threshold. The same is true of the suggestions by numerous tax academics considering how to tax the rich.

“Those in the 1 percent are walking off with the riches, but in doing so they have provided nothing but anxiety and insecurity to the 99 percent,” explained Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz in his 2012 book The Price of Inequality. The “main fault line in the American society is . . . between the 1 percent and everybody else,” insisted celebrated economists Emanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman in their book The Triumph of Injustice, published amid the 2020 presidential campaign. Dramatic wealth tax proposals by Democratic presidential candidates Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, chair of the tax-writing committee Senator Ron Wyden, and even an income taxation plan by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez do not come close to hiking taxes on anyone below the 1 percent threshold. The same is true of the suggestions by numerous tax academics considering how to tax the rich. Until last summer, we had a dead frog in our freezer. When Bunky died, George and I thought we should wait to bury him till both our grown children were home, so we put him in a Ziploc bag and propped him on his side on a shallow shelf in the freezer door, just above the icemaker. Bunky was flat and compact and, very soon, as rigid as a cell phone. He fit perfectly. I’d always wondered what KitchenAid intended that shelf for—it was too narrow for any food I could think of—but now we knew. It was intended to hold a frog.

Until last summer, we had a dead frog in our freezer. When Bunky died, George and I thought we should wait to bury him till both our grown children were home, so we put him in a Ziploc bag and propped him on his side on a shallow shelf in the freezer door, just above the icemaker. Bunky was flat and compact and, very soon, as rigid as a cell phone. He fit perfectly. I’d always wondered what KitchenAid intended that shelf for—it was too narrow for any food I could think of—but now we knew. It was intended to hold a frog. Their fondness for animals. A multistory pet shop: canaries on the second floor, great apes at the top. A couple of years ago, a man was arrested on Fifth Avenue for driving a giraffe around in his truck. He explained that his giraffe didn’t get enough air out in the suburbs where he kept it and that he’d found this to be a good way to get it some air. In Central Park, a lady brought a gazelle to graze. To the court, she explained that the gazelle was a person. “Yet it doesn’t speak,” the judge said. “Oh, yes, it speaks the language of lovingkindness.” Five-dollar fine. There’s also the three-kilometer tunnel under the Hudson and the impressive bridge to New Jersey.

Their fondness for animals. A multistory pet shop: canaries on the second floor, great apes at the top. A couple of years ago, a man was arrested on Fifth Avenue for driving a giraffe around in his truck. He explained that his giraffe didn’t get enough air out in the suburbs where he kept it and that he’d found this to be a good way to get it some air. In Central Park, a lady brought a gazelle to graze. To the court, she explained that the gazelle was a person. “Yet it doesn’t speak,” the judge said. “Oh, yes, it speaks the language of lovingkindness.” Five-dollar fine. There’s also the three-kilometer tunnel under the Hudson and the impressive bridge to New Jersey. Stephanie Blendermann, 65, had good reason to worry about heart disease. Three of her sisters died in their 40s or early 50s from heart attacks, and her father needed surgery to bypass clogged arteries. She also suffered from an autoimmune disorder that results in chronic inflammation and boosts the odds of developing cardiovascular illnesses. “I have an interesting medical chart,” says Blendermann, a real estate agent in Prior Lake, Minnesota.

Stephanie Blendermann, 65, had good reason to worry about heart disease. Three of her sisters died in their 40s or early 50s from heart attacks, and her father needed surgery to bypass clogged arteries. She also suffered from an autoimmune disorder that results in chronic inflammation and boosts the odds of developing cardiovascular illnesses. “I have an interesting medical chart,” says Blendermann, a real estate agent in Prior Lake, Minnesota. What is synthetic biology and what are scientists trying to do with it? Simply put, we could say that synthetic biology is a fusion of biology, especially molecular biology, and engineering. The distinctive thing about it is that it treats cells as programmable devices. It’s a kind of tinker toy approach that builds circuits, but not out of wires and switches like we’re used to, but rather out of biological components, like proteins and genes. Programming cells in this way isn’t really all that different from programming computers, except that the programming language isn’t Python, or C++. It’s the language of biology, the language of DNA, with the goal of making proteins that will interact with each other in some clever ways.

What is synthetic biology and what are scientists trying to do with it? Simply put, we could say that synthetic biology is a fusion of biology, especially molecular biology, and engineering. The distinctive thing about it is that it treats cells as programmable devices. It’s a kind of tinker toy approach that builds circuits, but not out of wires and switches like we’re used to, but rather out of biological components, like proteins and genes. Programming cells in this way isn’t really all that different from programming computers, except that the programming language isn’t Python, or C++. It’s the language of biology, the language of DNA, with the goal of making proteins that will interact with each other in some clever ways.