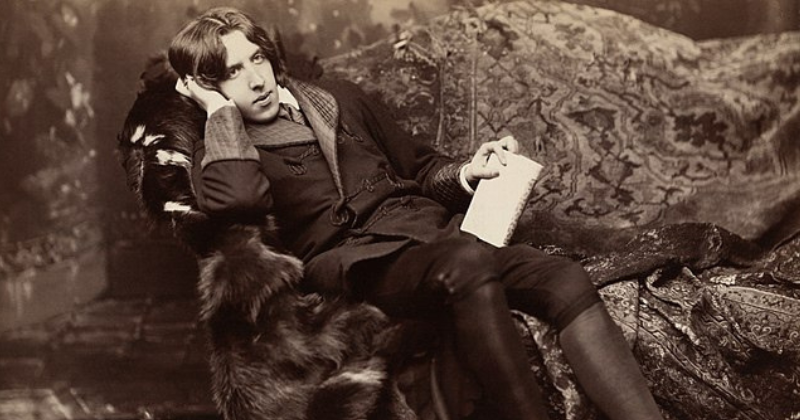

Alexander Poots in Literary Hub:

When still a boy, Forrest Reid saw Oscar Wilde in Belfast.

When still a boy, Forrest Reid saw Oscar Wilde in Belfast.

I beheld my first celebrity. Not that I knew him to be celebrated, but I could see for myself his appearance was remarkable. I had been taught that it was rude to stare, but on this occasion, though I was with my mother, I could not help staring, and even feeling I was intended to do so. He was, my mother told me, a Mr. Oscar Wilde.

Reid presents his boyhood sighting of the famous writer as little more than a curious anecdote. He was 20 years old in 1895, the year of the Wilde Affair. In early April of that year, the newspapers were full of Wilde’s lawsuit against the Marquess of Queensberry. Just a few weeks later, the papers were full of Wilde’s fall from grace. He became a byword for infamy in England and Ireland. Worst of all, his very name became a slur.

Reid lived through it all. The man he had seen promenading through Belfast was now circling a prison yard. How did they make him feel, those broadsheets at the breakfast table? Perhaps they frightened him. An unwelcome premonition of his own future. Desire reduced to commerce, letters sent and regretted, a life spent waiting for the blackmailer’s note or the policeman’s knock. And yet even then Reid must have known that his life, queer fellow though he was, would not take that shape. Wilde’s passions were shallower than Reid’s, and much more dangerous.

More here.

Welcome to another episode of Sean Carroll’s Mindscape. Today, we’re joined by Raphaël Millière, a philosopher and cognitive scientist at Columbia University. We’ll be exploring the fascinating topic of how artificial intelligence thinks and processes information. As AI becomes increasingly prevalent in our daily lives, it’s important to understand the mechanisms behind its decision-making processes. What are the algorithms and models that underpin AI, and how do they differ from human thought processes? How do machines learn from data, and what are the limitations of this learning? These are just some of the questions we’ll be exploring in this episode. Raphaël will be sharing insights from his work in cognitive science, and discussing the latest developments in this rapidly evolving field. So join us as we dive into the mind of artificial intelligence and explore how it thinks.

Welcome to another episode of Sean Carroll’s Mindscape. Today, we’re joined by Raphaël Millière, a philosopher and cognitive scientist at Columbia University. We’ll be exploring the fascinating topic of how artificial intelligence thinks and processes information. As AI becomes increasingly prevalent in our daily lives, it’s important to understand the mechanisms behind its decision-making processes. What are the algorithms and models that underpin AI, and how do they differ from human thought processes? How do machines learn from data, and what are the limitations of this learning? These are just some of the questions we’ll be exploring in this episode. Raphaël will be sharing insights from his work in cognitive science, and discussing the latest developments in this rapidly evolving field. So join us as we dive into the mind of artificial intelligence and explore how it thinks. The run on Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) – on which

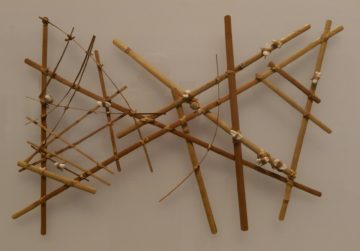

The run on Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) – on which  Wave charts aren’t maps so much as mnemonic devices. They’re not brought on board in order to navigate; rather, the navigator makes them as a personal reference, studying them while on land and bringing that knowledge onto the sea. There were

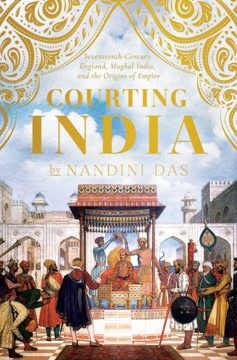

Wave charts aren’t maps so much as mnemonic devices. They’re not brought on board in order to navigate; rather, the navigator makes them as a personal reference, studying them while on land and bringing that knowledge onto the sea. There were  Pity Sir Thomas Roe. He was sent to India in February 1615 by James I as the first English ambassador to the fabulously glamorous Mughal court – a privilege and an extraordinary opportunity, one might think. But diplomats in the 17th century, in Europe at least, were woefully underpaid and were expected to make up any shortfall out of their own pockets in anticipation of a refund on their return. The amount reimbursed was at the whim of the monarch, who might be grateful for their years of travail but might just as easily be disappointed or no longer interested. It is a measure of their unrealistic expectations that the East India Company, formed only fifteen years before Roe set off on the hazardous six-month voyage to India and partial sponsors of his expedition, imagined that the ‘Grand Mogore’ might be persuaded to give Roe an allowance, enabling him to return their investment in him.

Pity Sir Thomas Roe. He was sent to India in February 1615 by James I as the first English ambassador to the fabulously glamorous Mughal court – a privilege and an extraordinary opportunity, one might think. But diplomats in the 17th century, in Europe at least, were woefully underpaid and were expected to make up any shortfall out of their own pockets in anticipation of a refund on their return. The amount reimbursed was at the whim of the monarch, who might be grateful for their years of travail but might just as easily be disappointed or no longer interested. It is a measure of their unrealistic expectations that the East India Company, formed only fifteen years before Roe set off on the hazardous six-month voyage to India and partial sponsors of his expedition, imagined that the ‘Grand Mogore’ might be persuaded to give Roe an allowance, enabling him to return their investment in him. A recent podcast series digs into the beginnings of conservative talk radio and tracks its rise. NPR’s Steve Inskeep talks to Katie Thornton, the host of “The Divided Dial.”

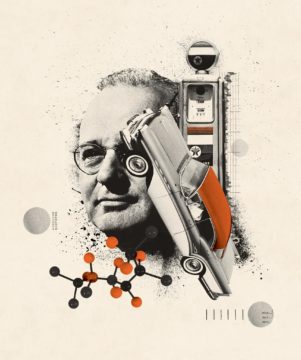

A recent podcast series digs into the beginnings of conservative talk radio and tracks its rise. NPR’s Steve Inskeep talks to Katie Thornton, the host of “The Divided Dial.” It was said that Thomas Midgley Jr. had the finest lawn in America. Golf-club chairmen from across the Midwest would visit his estate on the outskirts of Columbus, Ohio, purely to admire the grounds; the Scott Seed Company eventually put an image of Midgley’s lawn on its letterhead. Midgley cultivated his acres of grass with the same compulsive innovation that characterized his entire career. He installed a wind gauge on the roof that would sound an alarm in his bedroom, alerting him whenever the lawn risked being desiccated by a breeze. Fifty years before the arrival of smart-home devices, Midgley wired up the rotary telephone in his bedroom so that a few spins of the dial would operate the sprinklers.

It was said that Thomas Midgley Jr. had the finest lawn in America. Golf-club chairmen from across the Midwest would visit his estate on the outskirts of Columbus, Ohio, purely to admire the grounds; the Scott Seed Company eventually put an image of Midgley’s lawn on its letterhead. Midgley cultivated his acres of grass with the same compulsive innovation that characterized his entire career. He installed a wind gauge on the roof that would sound an alarm in his bedroom, alerting him whenever the lawn risked being desiccated by a breeze. Fifty years before the arrival of smart-home devices, Midgley wired up the rotary telephone in his bedroom so that a few spins of the dial would operate the sprinklers. English may have become universal, but not everyone believes it is a gift. In fact, many hold diametrically opposite views. In an article in The Guardian in 2018, the journalist Jacob Mikanowski described English as a ‘behemoth, bully, loudmouth, thief’, highlighting that the dominance of English threatens local cultures and languages. Due to the ways in which English continues to gain ground worldwide, many languages are becoming

English may have become universal, but not everyone believes it is a gift. In fact, many hold diametrically opposite views. In an article in The Guardian in 2018, the journalist Jacob Mikanowski described English as a ‘behemoth, bully, loudmouth, thief’, highlighting that the dominance of English threatens local cultures and languages. Due to the ways in which English continues to gain ground worldwide, many languages are becoming  Recent investigations like the one Dyer worked on have revealed that LLMs can produce hundreds of “emergent” abilities — tasks that big models can complete that smaller models can’t, many of which seem to have little to do with analyzing text. They range from multiplication to generating executable computer code to, apparently, decoding movies based on emojis. New analyses suggest that for some tasks and some models, there’s a threshold of complexity beyond which the functionality of the model skyrockets. (They also suggest a dark flip side: As they increase in complexity, some models reveal new biases and inaccuracies in their responses.)

Recent investigations like the one Dyer worked on have revealed that LLMs can produce hundreds of “emergent” abilities — tasks that big models can complete that smaller models can’t, many of which seem to have little to do with analyzing text. They range from multiplication to generating executable computer code to, apparently, decoding movies based on emojis. New analyses suggest that for some tasks and some models, there’s a threshold of complexity beyond which the functionality of the model skyrockets. (They also suggest a dark flip side: As they increase in complexity, some models reveal new biases and inaccuracies in their responses.) In a recent Substack post, free-range social critic Freddie deBoer

In a recent Substack post, free-range social critic Freddie deBoer  The first precept of survivors’ justice is the desire for community acknowledgment that a wrong has been done. This makes intuitive sense. If secrecy and denial are the tyrant’s first line of defense, then public truth telling must be the first act of a survivor’s resistance, and recognizing the survivor’s claim to justice must be the moral community’s first act of solidarity.

The first precept of survivors’ justice is the desire for community acknowledgment that a wrong has been done. This makes intuitive sense. If secrecy and denial are the tyrant’s first line of defense, then public truth telling must be the first act of a survivor’s resistance, and recognizing the survivor’s claim to justice must be the moral community’s first act of solidarity. A

A This week the conservative writer Bethany Mandel had the kind of moment that can happen to anyone who talks in public for a living: While promoting a new book critiquing progressivism, she was asked to define the term “woke” by an interviewer — a reasonable question, but one that made her brain freeze and her words stumble. The viral

This week the conservative writer Bethany Mandel had the kind of moment that can happen to anyone who talks in public for a living: While promoting a new book critiquing progressivism, she was asked to define the term “woke” by an interviewer — a reasonable question, but one that made her brain freeze and her words stumble. The viral