Phil Christman in The Hedgehog Review:

It’s all wrong. The wrongness is pervasive; you could not, if asked, identify the it or the its that went wrong. Wrongness leaches into everything, like the microplastics you read about, which may or may not be reducing sperm count in men, which may or may not be good, in the long run—it’s something to do with the environment. Someone wanted you to feel one way or the other about it, but you can’t remember who or why or whether you agreed with him. Everyone speaks so authoritatively, whether it’s on the evening news or a podcast, in an Internet video or a book, or even in one of those Twitter threads that begins (irksomely, you once felt, but now you don’t notice) with the little picture of a spool. Authority makes them all sound the same; it crosses all their faces and leaves many of the same furrows. Only afterward, trying to add it all up, do you half-remember that none of them agreed with each other. But the wrongness you can be sure of. It is like God, undergirding all things.

It’s all wrong. The wrongness is pervasive; you could not, if asked, identify the it or the its that went wrong. Wrongness leaches into everything, like the microplastics you read about, which may or may not be reducing sperm count in men, which may or may not be good, in the long run—it’s something to do with the environment. Someone wanted you to feel one way or the other about it, but you can’t remember who or why or whether you agreed with him. Everyone speaks so authoritatively, whether it’s on the evening news or a podcast, in an Internet video or a book, or even in one of those Twitter threads that begins (irksomely, you once felt, but now you don’t notice) with the little picture of a spool. Authority makes them all sound the same; it crosses all their faces and leaves many of the same furrows. Only afterward, trying to add it all up, do you half-remember that none of them agreed with each other. But the wrongness you can be sure of. It is like God, undergirding all things.

More here.

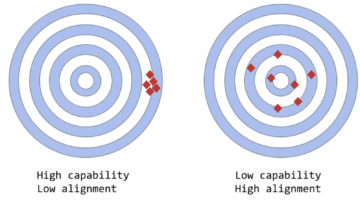

The creators have used a combination of both Supervised Learning and Reinforcement Learning to fine-tune ChatGPT, but it is the Reinforcement Learning component specifically that makes ChatGPT unique. The creators use a particular technique called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), which uses human feedback in the training loop to minimize harmful, untruthful, and/or biased outputs.

The creators have used a combination of both Supervised Learning and Reinforcement Learning to fine-tune ChatGPT, but it is the Reinforcement Learning component specifically that makes ChatGPT unique. The creators use a particular technique called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), which uses human feedback in the training loop to minimize harmful, untruthful, and/or biased outputs. For years, philanthropists have poured money into progressive climate groups, while

For years, philanthropists have poured money into progressive climate groups, while

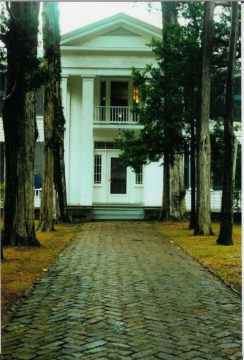

After I’d wandered the grounds, I spent the weekend in Oxford, a heady experience for a Northern fetishist of things Southern. I ate catfish and grits, drank whiskey in a bar on the outskirts of town where old men in hats played guitars. I visited Faulkner’s grave and his birthplace, drove around the Mississippi hill country, and ate okra with congenial strangers. I tried to understand why I felt drawn to this part of the world. To that end, I drank whiskey in a second bar, this one downtown, overlooking the statue of the Confederate soldier who gazed “with empty eyes,” in Faulkner’s phrase, at the square. I decided the reason was this. I grew up in Amherst, a mile down the road from Dickinson’s house, and Massachusetts is the Mississippi of the North, Mississippi the Massachusetts of the South. They’re on opposite sides of the American political spectrum, but they’re both places where the present is dwarfed and chastened by the past. In Massachusetts, a given location is known as the spot where the minutemen faced the redcoats on the green, or where Jonathan Edwards delivered his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” or where the Mayflower landed, or where the whalers set sail, or where the tea was dumped in the harbor. In Mississippi, it’s the same: here’s where Grant’s army bivouacked; here’s where the formerly enslaved Union soldiers drove the Texans from the field; here’s where Elvis grew up; here’s where Emmett Till was murdered; here’s where the earliest blues music was performed. I’ve heard both Massachusetts and Mississippi maligned as boring, and I’ve tried to explain to the maligners: You need to stop living so much in the present.

After I’d wandered the grounds, I spent the weekend in Oxford, a heady experience for a Northern fetishist of things Southern. I ate catfish and grits, drank whiskey in a bar on the outskirts of town where old men in hats played guitars. I visited Faulkner’s grave and his birthplace, drove around the Mississippi hill country, and ate okra with congenial strangers. I tried to understand why I felt drawn to this part of the world. To that end, I drank whiskey in a second bar, this one downtown, overlooking the statue of the Confederate soldier who gazed “with empty eyes,” in Faulkner’s phrase, at the square. I decided the reason was this. I grew up in Amherst, a mile down the road from Dickinson’s house, and Massachusetts is the Mississippi of the North, Mississippi the Massachusetts of the South. They’re on opposite sides of the American political spectrum, but they’re both places where the present is dwarfed and chastened by the past. In Massachusetts, a given location is known as the spot where the minutemen faced the redcoats on the green, or where Jonathan Edwards delivered his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” or where the Mayflower landed, or where the whalers set sail, or where the tea was dumped in the harbor. In Mississippi, it’s the same: here’s where Grant’s army bivouacked; here’s where the formerly enslaved Union soldiers drove the Texans from the field; here’s where Elvis grew up; here’s where Emmett Till was murdered; here’s where the earliest blues music was performed. I’ve heard both Massachusetts and Mississippi maligned as boring, and I’ve tried to explain to the maligners: You need to stop living so much in the present. It has been over two years since a violent mob attacked and occupied the United States Capitol in an effort to overturn the 2020 election. While blame has been laid at the feet of then-president Donald Trump and his most ardent supporters, religion scholar Bradley Onishi takes a close look at the historical events and forces that led up to the attack.

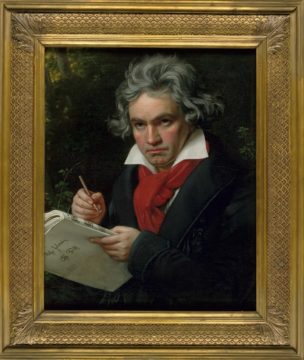

It has been over two years since a violent mob attacked and occupied the United States Capitol in an effort to overturn the 2020 election. While blame has been laid at the feet of then-president Donald Trump and his most ardent supporters, religion scholar Bradley Onishi takes a close look at the historical events and forces that led up to the attack. It was March 1827 and Ludwig van Beethoven was dying. As he lay in bed, wracked with abdominal pain and jaundiced, grieving friends and acquaintances came to visit. And some asked a favor: Could they clip a lock of his hair for remembrance? The parade of mourners continued after Beethoven’s death at age 56, even after doctors performed a gruesome craniotomy, looking at the folds in Beethoven’s brain and removing his ear bones in a vain attempt to understand why the revered composer lost his hearing.

It was March 1827 and Ludwig van Beethoven was dying. As he lay in bed, wracked with abdominal pain and jaundiced, grieving friends and acquaintances came to visit. And some asked a favor: Could they clip a lock of his hair for remembrance? The parade of mourners continued after Beethoven’s death at age 56, even after doctors performed a gruesome craniotomy, looking at the folds in Beethoven’s brain and removing his ear bones in a vain attempt to understand why the revered composer lost his hearing. FOR MANY AMERICANS,

FOR MANY AMERICANS, T

T There are three main themes to this book. First, people revered eagles and used them and their images to define their group, be it native or settler. Second, people killed bald eagles by the thousands, nearly wiping out this magnificent bird, a job that DDT practically completed. The third theme is redemption and shows the efforts some people are making to rescue our emblematic bird.

There are three main themes to this book. First, people revered eagles and used them and their images to define their group, be it native or settler. Second, people killed bald eagles by the thousands, nearly wiping out this magnificent bird, a job that DDT practically completed. The third theme is redemption and shows the efforts some people are making to rescue our emblematic bird. Imagine there’s a small fire in your kitchen. Your fire alarm goes off, warning everyone nearby about the danger. Someone calls 911. You try to put the fire out yourself — maybe you even have a fire extinguisher under the sink. If that doesn’t work, you know how to safely evacuate. By the time you get outside, a fire truck is already pulling up. Firefighters use the hydrant in front of your house to extinguish the flames before any of your neighbors’ homes are ever at risk of catching fire.

Imagine there’s a small fire in your kitchen. Your fire alarm goes off, warning everyone nearby about the danger. Someone calls 911. You try to put the fire out yourself — maybe you even have a fire extinguisher under the sink. If that doesn’t work, you know how to safely evacuate. By the time you get outside, a fire truck is already pulling up. Firefighters use the hydrant in front of your house to extinguish the flames before any of your neighbors’ homes are ever at risk of catching fire. Whatever progress had been made in Afghanistan after the US invaded and removed the Taliban government that had provided a safe haven to the al-Qaeda terrorists who planned and carried out the 9/11 attacks, it was deemed inadequate. Many in the Bush administration were motivated by a desire to bring democracy to the entire Middle East, and Iraq was viewed as the ideal country to set the transition in motion. Democratization there would set an example that others across the region would be unable to resist following. And Bush himself wanted to do something big and bold.

Whatever progress had been made in Afghanistan after the US invaded and removed the Taliban government that had provided a safe haven to the al-Qaeda terrorists who planned and carried out the 9/11 attacks, it was deemed inadequate. Many in the Bush administration were motivated by a desire to bring democracy to the entire Middle East, and Iraq was viewed as the ideal country to set the transition in motion. Democratization there would set an example that others across the region would be unable to resist following. And Bush himself wanted to do something big and bold. We environmentalists spend our lives thinking about ways the world will end. There’s nowhere that I see

We environmentalists spend our lives thinking about ways the world will end. There’s nowhere that I see  Researchers have discovered an entirely new kind of taste receptor that allows fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) to detect alkaline substances — those that have a high pH — and avoid toxic meals and surfaces. Finding a new taste receptor in such a well-studied animal is unexpected, says Emily Liman, a neurobiologist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “I found it quite surprising that there is this whole new type of taste,” says Liman. “It is really beautiful work.” The discovery, published in Nature Metabolism this week

Researchers have discovered an entirely new kind of taste receptor that allows fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) to detect alkaline substances — those that have a high pH — and avoid toxic meals and surfaces. Finding a new taste receptor in such a well-studied animal is unexpected, says Emily Liman, a neurobiologist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “I found it quite surprising that there is this whole new type of taste,” says Liman. “It is really beautiful work.” The discovery, published in Nature Metabolism this week