Category: Archives

7 ways teachers can use Chat Gpt in the classroom!

From History4Humans:

I got to admit, when I pictured the robots 🤖 coming, I didn’t think they’d be here to do our students’ homework and write their essays, but that day has arrived! Many schools and districts around the country have already put the site behind a firewall but trust me, the cat is out of the bag and its not going back in! I do not think that is the right call and I think we must get ahead of this instead of trying to ineffectually sweep it under the rug. So, I wanted to write a little article about how teachers can use Chat GPT in the classroom. So, if you don’t know, CHATGPT is an AI software (currently free to use though that might change soon) that can do a ton of writing tasks when given commands. Students can use chatgpt to ask questions and receive answers or to generate entire written assignments based on any prompt.

I got to admit, when I pictured the robots 🤖 coming, I didn’t think they’d be here to do our students’ homework and write their essays, but that day has arrived! Many schools and districts around the country have already put the site behind a firewall but trust me, the cat is out of the bag and its not going back in! I do not think that is the right call and I think we must get ahead of this instead of trying to ineffectually sweep it under the rug. So, I wanted to write a little article about how teachers can use Chat GPT in the classroom. So, if you don’t know, CHATGPT is an AI software (currently free to use though that might change soon) that can do a ton of writing tasks when given commands. Students can use chatgpt to ask questions and receive answers or to generate entire written assignments based on any prompt.

I actually just had it write out a screen play for President Washington meeting with his cabinet to discuss the constitutionality of the Bank except it was a Seinfeld episode and it was pretty funny while still having Jefferson opposed to the Bank, Washington neutral at first, and Hamilton in support. (Jefferson, as Kramer wanted to use a cardboard box with some gold coins instead of a national bank 🤣).

But seriously, this has many teachers (and tons of other professions) freaking out.

Is it the end of homework? The takehome essay? Critical thinking?

NOPE!

More here.

Sometimes painted with a single eyelash, Willard Wigan’s tiny sculptures fit in the eye of a needle

Julia Binswanger in Smithsonian:

Artist Willard Wigan is famous for his recreations of famous paintings like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, as well his depictions of famous figures like William Shakespeare and Robin Hood. But in order to view them, you’ll need a microscope. Wigan’s new show, “Miniature Masterpieces,” is currently on display at Wollaton Hall in Nottingham, England. The free exhibition features 20 tiny sculptures, each of which sits in the eye of a needle.

Artist Willard Wigan is famous for his recreations of famous paintings like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, as well his depictions of famous figures like William Shakespeare and Robin Hood. But in order to view them, you’ll need a microscope. Wigan’s new show, “Miniature Masterpieces,” is currently on display at Wollaton Hall in Nottingham, England. The free exhibition features 20 tiny sculptures, each of which sits in the eye of a needle.

“This is more complicated than any microsurgery,” Wigan tells Wired in a video interview. “I don’t care what anybody says. You have to have a more stable hand than any surgeon to do this work.” Perhaps this sounds like an exaggeration, but careless mistakes can put an end to weeks of progress. Once, after finishing a sculpture depicting a scene from Alice in Wonderland, Wigan’s phone rang. “I went, ‘Who’s that?’ And as I breathed in, I inhaled Alice,” he tells Wired. “Gone. Somewhere in my cavities.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Believe, Believe

Believe in this. Young apple seeds,

In blue skies, radiating young breast,

Not in blue-suited insects,

Infesting society’s garments.

Believe in the swinging sounds of jazz,

Tearing the night into intricate shreds,

Putting it back together again,

In cool logical patterns,

Not in the sick controllers,

Who created only the Bomb.

Let the voices of dead poets

Ring louder in your ears

Than the screechings mouthed

In mildewed editorials.

Listen to the music of centuries,

Rising above the mushroom time

By Bob Kaufman

from Cranial Guitar

Coffee House Press, 1996

Tuesday, April 18, 2023

A life of splendid uselessness is a life well lived

Joseph M Keegin in Psyche:

Great art and thought have always been motivated by something other than mere moneymaking, even if moneymaking happened somewhere along the way. But our culture of instrumentality has settled like a thick fog over the idea that some activities are worth pursuing simply because they share in the beautiful, the good, or the true. No amount of birdwatching will win a person the presidency or a Beverly Hills mansion; making music with friends will not cure cancer or establish a colony on Mars. But the real project of humanity – of understanding ourselves as human beings, making a good world to live in, and striving together toward mutual flourishing – depends paradoxically upon the continued pursuit of what Hitz calls ‘splendid uselessness’.

Great art and thought have always been motivated by something other than mere moneymaking, even if moneymaking happened somewhere along the way. But our culture of instrumentality has settled like a thick fog over the idea that some activities are worth pursuing simply because they share in the beautiful, the good, or the true. No amount of birdwatching will win a person the presidency or a Beverly Hills mansion; making music with friends will not cure cancer or establish a colony on Mars. But the real project of humanity – of understanding ourselves as human beings, making a good world to live in, and striving together toward mutual flourishing – depends paradoxically upon the continued pursuit of what Hitz calls ‘splendid uselessness’.

The culture of the 21st century – on an increasingly planetary scale – is oriented around the practical principles of utility, effectiveness and impact. The worth of anything – an idea, an activity, an artwork, a relationship with another person – is determined pragmatically: things are good to the extent that they are instrumental, with instrumentality usually defined as the capacity to produce money or things.

More here.

Are coincidences real?

Paul Broks in The Guardian:

The biography of the actor Anthony Hopkins contains a striking example of a serendipitous coincidence. When he first heard he’d been cast to play a part in the film The Girl from Petrovka (1974), Hopkins went in search of a copy of the book on which it was based, a novel by George Feifer. He combed the bookshops of London in vain and, somewhat dejected, gave up and headed home. Then, to his amazement, he spotted a copy of The Girl from Petrovka lying on a bench at Leicester Square station. He recounted the story to Feifer when they met on location, and it transpired that the book Hopkins had stumbled upon was the very one that the author had mislaid in another part of London – an advance copy full of red-ink amendments and marginal notes he’d made in preparation for a US edition.

The biography of the actor Anthony Hopkins contains a striking example of a serendipitous coincidence. When he first heard he’d been cast to play a part in the film The Girl from Petrovka (1974), Hopkins went in search of a copy of the book on which it was based, a novel by George Feifer. He combed the bookshops of London in vain and, somewhat dejected, gave up and headed home. Then, to his amazement, he spotted a copy of The Girl from Petrovka lying on a bench at Leicester Square station. He recounted the story to Feifer when they met on location, and it transpired that the book Hopkins had stumbled upon was the very one that the author had mislaid in another part of London – an advance copy full of red-ink amendments and marginal notes he’d made in preparation for a US edition.

More here. [And here’s a coincidence I wrote about at 3QD some years ago.]

Taxing the Superrich

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman in the Boston Review:

Much has been written about the dramatic increase in income and wealth inequality in the United States over the last four decades. This volume of literature not only warns about the injustice of our current system, but also raises alarm that extreme inequality poses a serious risk to our democracy.

Much has been written about the dramatic increase in income and wealth inequality in the United States over the last four decades. This volume of literature not only warns about the injustice of our current system, but also raises alarm that extreme inequality poses a serious risk to our democracy.

Concern about inequality is at least as old as the United States itself. Writing in 1792 about the necessity and dangers of political parties, James Madison made the connection between excessive wealth and its political influence:

The great object should be to combat the evil: 1. By establishing a political equality among all. 2. By withholding unnecessary opportunities from a few, to increase the inequality of property, by an immoderate, and especially an unmerited, accumulation of riches. 3. By the silent operation of laws, which, without violating the rights of property, reduce extreme wealth towards a state of mediocrity, and raise extreme indigence towards a state of comfort.

Excessive wealth concentration, in Madison’s view, was as poisonous for democracy as war. “In war,” he continued, “the discretionary power of the executive is extended; its influence in dealing out offices, honors, and emoluments is multiplied. . . . The same malignant aspect in republicanism may be traced in the inequality of fortunes.”

Wealth is power. An extreme concentration of wealth means an extreme concentration of power: the power to influence government policy, the power to stifle competition, the power to shape ideology.

More here.

60 Minutes: Google’s developers on the future of artificial intelligence

Sister Nivedita on Love and Death

Maria Popova at Brain Pickings:

Know as we might what actually happens when we die, we spend our lives trembling at the fact of our finitude, trying to wrest from it some greater poetic truth — something that slakes the soul’s thirst for meaning. Even the spiritual materialists among us are haunted by incomprehension at the cessation of consciousness — how can this entire carnival of wonder just, one day, melt into nothingness? And what, in the end, does it all mean, will it all have meant?

Know as we might what actually happens when we die, we spend our lives trembling at the fact of our finitude, trying to wrest from it some greater poetic truth — something that slakes the soul’s thirst for meaning. Even the spiritual materialists among us are haunted by incomprehension at the cessation of consciousness — how can this entire carnival of wonder just, one day, melt into nothingness? And what, in the end, does it all mean, will it all have meant?

These questions come alive in the 1908 book An Indian Study of Love and Death (public library | public domain) by the Irish teacher and activist Margaret Elizabeth Noble (October 18, 1867–October 13, 1911), christened Sister Nivedita by Swami Vivekananda after she emigrated to Calcutta when she was twenty-one to begin devoting her life to India and the sacred search for meaning.

more here.

Plant of the Month: London Rocket

Beth Kidd at JSTOR Daily:

Throughout 1667, the ruins of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral became overgrown with a thicket of weeds. One yellow-flowered plant in particular mounted the walls in huge quantities. That spring, on the south side of the church, “it grew as thick as could be; nay, on the very top of the tower,” wrote the antiquary John Aubrey, reminiscing some years later. In September 1666, a terrible fire, beginning in a bakery on “Pudding Lane,” had swept through the city, destroying the homes of thousands. But it also left in its wake apparently fertile ground for plants. Some, like the yellow flower of St Paul’s, had been identified rarely before the Great Fire. So dramatically did this particular plant burst onto the scene that expert botanist and royal physician Robert Morison presumed it had sprung from the ashes themselves. Morison was here calling upon a theory of “spontaneous generation” of life from non-living or decayed material, proposed as early as Aristotle and still popular, as William Keezer explains, in the seventeenth century.

Throughout 1667, the ruins of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral became overgrown with a thicket of weeds. One yellow-flowered plant in particular mounted the walls in huge quantities. That spring, on the south side of the church, “it grew as thick as could be; nay, on the very top of the tower,” wrote the antiquary John Aubrey, reminiscing some years later. In September 1666, a terrible fire, beginning in a bakery on “Pudding Lane,” had swept through the city, destroying the homes of thousands. But it also left in its wake apparently fertile ground for plants. Some, like the yellow flower of St Paul’s, had been identified rarely before the Great Fire. So dramatically did this particular plant burst onto the scene that expert botanist and royal physician Robert Morison presumed it had sprung from the ashes themselves. Morison was here calling upon a theory of “spontaneous generation” of life from non-living or decayed material, proposed as early as Aristotle and still popular, as William Keezer explains, in the seventeenth century.

more here.

The Origins of Creativity

Louis Menand in The New Yorker:

What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction? Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago:

What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction? Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago:

This does read like a novel. Is it nonfiction? The only source the author cites for this paragraph verifies the statement “weeks of severe cold.” Presumably, the “Christmas storm” has a source, too, perhaps in newspapers of the time (1776). The rest—the light, the exact depth of frozen ground, the packed ice, the ruts, the riders’ mindfulness, the walking horses—seems to have been extrapolated in order to unfold a dramatic scene, evoke a mental picture. There is also the novelistic device of delaying the identification of the characters. It isn’t until the third paragraph that we learn that one of the horsemen is none other than John Adams! It’s all perfectly plausible, but much of it is imagined. Is being “creative” simply a license to embellish? Is there a point beyond which inference becomes fantasy?

More here.

Women’s silent sadness

Howard Zinn in Delancey Place:

After the Revolution in the United States, American society coalesced around controlling women’s behavior and sexual activity while exploiting their labor. Women’s “reduced rate,” or free labor in the case of slaves, was critical to the growing economy. And they were coerced, compelled, and conditioned to be meekly submissive. They were encouraged to “not expect too much”:

After the Revolution in the United States, American society coalesced around controlling women’s behavior and sexual activity while exploiting their labor. Women’s “reduced rate,” or free labor in the case of slaves, was critical to the growing economy. And they were coerced, compelled, and conditioned to be meekly submissive. They were encouraged to “not expect too much”:

“[A]fter the Revolution, none of the new state constitutions granted women the right to vote, except for New Jersey, and that state rescinded the right in 1807. New York’s constitution specifically disfranchised women by using the word ‘male.’

While perhaps 90 percent of the white male population were literate around 1750, only 40 percent of the women were. Working-class women had little means of communicating, and no means of recording whatever sentiments of rebelliousness they may have felt at their subordination. Not only were they bearing children in great numbers, under great hardships, but they were working in the home. Around the time of the Declaration of Independence, four thousand women and children in Philadelphia were spinning at home for local plants under the ‘putting out’ system. Women also were shopkeepers and innkeepers and engaged in many trades. They were bakers, tinworkers, brewers, tanners, ropemakers, lumberjacks, printers, morticians, woodworkers, staymakers, and more. Ideas of female equality were in the air during and after the Revolution. Tom Paine spoke out for the equal rights of women. And the pioneering book of Mary Wollstonecraft in England, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, was reprinted in the United States shortly after the Revolutionary War.

Wollstonecraft was responding to the English conservative and opponent of the French Revolution, Edmund Burke, who had written in his Reflections on the Revolution in France that ‘a woman is but an animal, and an animal not of the highest order.’

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Mending Wall

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of outdoor game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

by Robert Frost – 1874-1963

from The Poetry of Robert Frost

Ballantine Books, 1970

Anti-Realism – Searle & Putnam

Sunday, April 16, 2023

The late poet Charles Simic was a chess prodigy

Adrienne Raphel at JSTOR Daily:

Charles Simic, the late, great Serbian-American poet, was born in 1938 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. In 1941, when Simic was three, Hitler invaded, and a bomb explosion hurled Simic out of bed. Three years later, in 1944, another series of detonations exploded across town—this time, dropped by Allies. Images of a war-torn country inform Simic’s earliest memories. Belgrade had become a chess board, a deadly battleground for both the Nazis and Allies. Simic emigrated as a boy to the United States, and he wrote poetry in English, but the hellish landscape of his youth lay at the heart of his work.

Charles Simic, the late, great Serbian-American poet, was born in 1938 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. In 1941, when Simic was three, Hitler invaded, and a bomb explosion hurled Simic out of bed. Three years later, in 1944, another series of detonations exploded across town—this time, dropped by Allies. Images of a war-torn country inform Simic’s earliest memories. Belgrade had become a chess board, a deadly battleground for both the Nazis and Allies. Simic emigrated as a boy to the United States, and he wrote poetry in English, but the hellish landscape of his youth lay at the heart of his work.

Simic was also a chess prodigy, and the game rewired his brain. As he wrote in the New York Review of Books, “The kinds of poems I write—mostly short and requiring endless tinkering—often recall for me games of chess. They depend for their success on word and image being placed in proper order and their endings must have the inevitability and surprise of an elegantly executed checkmate.”

More here.

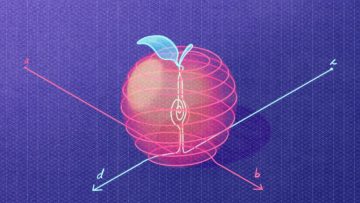

By imbuing enormous vectors with semantic meaning, we can get machines to reason more abstractly — and efficiently — than before

Anil Ananthaswamy in Quanta:

The key is that each piece of information, such as the notion of a car, or its make, model or color, or all of it together, is represented as a single entity: a hyperdimensional vector.

The key is that each piece of information, such as the notion of a car, or its make, model or color, or all of it together, is represented as a single entity: a hyperdimensional vector.

A vector is simply an ordered array of numbers. A 3D vector, for example, comprises three numbers: the x, y and z coordinates of a point in 3D space. A hyperdimensional vector, or hypervector, could be an array of 10,000 numbers, say, representing a point in 10,000-dimensional space. These mathematical objects and the algebra to manipulate them are flexible and powerful enough to take modern computing beyond some of its current limitations and foster a new approach to artificial intelligence.

“This is the thing that I’ve been most excited about, practically in my entire career,” Olshausen said. To him and many others, hyperdimensional computing promises a new world in which computing is efficient and robust, and machine-made decisions are entirely transparent.

More here.

Toward a Leisure Ethic

Stuart Whatley in The Hedgehog Review:

To most people today, the notion of a leisure ethic will sound foreign, paradoxical, and indeed subversive, even though leisure is still commonly associated with the good life. More than any other society in the past, ours certainly has the technology and the wealth to furnish more people with greater freedom over more of their time. Yet because we lack a shared leisure ethic, we have not availed ourselves of that option. Nor does it occur to us even to demand or strive for such a dispensation.

To most people today, the notion of a leisure ethic will sound foreign, paradoxical, and indeed subversive, even though leisure is still commonly associated with the good life. More than any other society in the past, ours certainly has the technology and the wealth to furnish more people with greater freedom over more of their time. Yet because we lack a shared leisure ethic, we have not availed ourselves of that option. Nor does it occur to us even to demand or strive for such a dispensation.

One reason for this is that the values and culture that created our current abundance may be incompatible with actually enjoying it. Sparta had the same problem.

More here.

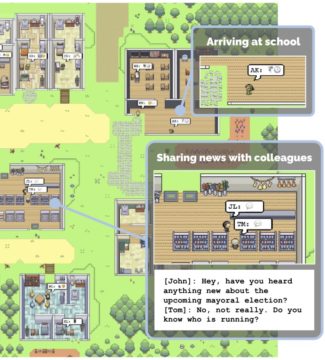

Researchers Let 25 AI Bots Loose Inside A Virtual Town and The Results Were Fascinating

Victor Tangermann at Futurism:

The researchers found that their agents could “produce believable individual and emergent social behaviors.” For instance, one agent attempted to throw a Valentine’s Day party by sending out invites and setting a time and place for the party.

The researchers found that their agents could “produce believable individual and emergent social behaviors.” For instance, one agent attempted to throw a Valentine’s Day party by sending out invites and setting a time and place for the party.

A Smallville mayoral race also included the kind of drama you’d expect to occur in a small town.

“To be honest, I don’t like Sam Moore,” an agent called Tom said after being asked what he thought of the mayoral candidate. “I think he’s out of touch with the community and doesn’t have our best interests at heart.”

It got even more human than that.

Vivan Sundaram (1943 – 2023) Visual Artist

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbp6ObL-ilI&ab_channel=NewsX