Claire Bishop at Artforum:

EACH PHASE of research-based art presents a different understanding of what constitutes knowledge and a different approach to spectatorial labor. In the first phase, the artist invites the viewer to piece together parts from the materials provided to form their own historical narrative and to experience in their bodies and minds the complexity of a given (usually counterhegemonic) topic. Knowledge aspires to be new knowledge. In the second phase, the viewer listens to or reads a narrative crafted by the artist. Facts may be partly fictionalized, but there remains a sense of correcting or enhancing history, often through a counter- or micronarrative. The third phase returns the viewer to sifting through information, albeit now in a formal, less interactive mode. Knowledge is the aggregation of preexisting data, and the work accordingly invites meta-reflection on the production of knowledge as truth. In each case, though, despite creating the look or atmosphere of research, artists are reluctant to draw conclusions. Many of these pieces convey a sense of being immersed—even lost—in data.

EACH PHASE of research-based art presents a different understanding of what constitutes knowledge and a different approach to spectatorial labor. In the first phase, the artist invites the viewer to piece together parts from the materials provided to form their own historical narrative and to experience in their bodies and minds the complexity of a given (usually counterhegemonic) topic. Knowledge aspires to be new knowledge. In the second phase, the viewer listens to or reads a narrative crafted by the artist. Facts may be partly fictionalized, but there remains a sense of correcting or enhancing history, often through a counter- or micronarrative. The third phase returns the viewer to sifting through information, albeit now in a formal, less interactive mode. Knowledge is the aggregation of preexisting data, and the work accordingly invites meta-reflection on the production of knowledge as truth. In each case, though, despite creating the look or atmosphere of research, artists are reluctant to draw conclusions. Many of these pieces convey a sense of being immersed—even lost—in data.

more here.

When the London newspaper the Athenian Mercury, edited and published by the author and bookseller John Dunton, first answered questions about romance, bodily functions, and the mysteries of the universe in 1691, it may have created the template for the advice column. But the history of advice stretches back even further into the past. Advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appears in ancient philosophical treatises, medieval medical manuals, and countless books. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring advice through the ages and into modern times in a series of readings and essays.

When the London newspaper the Athenian Mercury, edited and published by the author and bookseller John Dunton, first answered questions about romance, bodily functions, and the mysteries of the universe in 1691, it may have created the template for the advice column. But the history of advice stretches back even further into the past. Advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appears in ancient philosophical treatises, medieval medical manuals, and countless books. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring advice through the ages and into modern times in a series of readings and essays. One of the most astonishing passages in the Talmud, a book chock-full of astonishing passages, gingerly asks the question at the core of every single human pursuit: What, precisely, is the meaning of life?

One of the most astonishing passages in the Talmud, a book chock-full of astonishing passages, gingerly asks the question at the core of every single human pursuit: What, precisely, is the meaning of life? Once upon a time, when the famous scientist Albert Einstein worked at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, a tiny old woman approached him as he was walking home. She was schlepping a skinny young boy of about six who was dragging his feet.

Once upon a time, when the famous scientist Albert Einstein worked at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, a tiny old woman approached him as he was walking home. She was schlepping a skinny young boy of about six who was dragging his feet. There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy.

There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy. One Friday night in October 2018, during the inaugural Palestinian Theatre Festival in Ramallah, I watched The Freedom Theatre from Jenin refugee camp perform a play called Return to Palestine. In this tightly choreographed 45-minute piece of physical comedy, a young Palestinian-American named Jad travels back to Jenin, a city in the northern West Bank, to visit his family for the first time. The black-clad ensemble of six forms a line that transforms fluidly into a car, a checkpoint, the entrance to the refugee camp, a café, accompanied by an oud, spoons and drums played by musicians sitting stage-right.

One Friday night in October 2018, during the inaugural Palestinian Theatre Festival in Ramallah, I watched The Freedom Theatre from Jenin refugee camp perform a play called Return to Palestine. In this tightly choreographed 45-minute piece of physical comedy, a young Palestinian-American named Jad travels back to Jenin, a city in the northern West Bank, to visit his family for the first time. The black-clad ensemble of six forms a line that transforms fluidly into a car, a checkpoint, the entrance to the refugee camp, a café, accompanied by an oud, spoons and drums played by musicians sitting stage-right. The focus of Audubon at Sea is indicated by its subtitle: The Coastal and Transatlantic Adventures of John James Audubon. It argues that he was never so comfortable at sea as he was on land when “collecting”—i.e., shooting—his specimens. Seabirds were harder to see up close, we are told; they are more elusive and maddening to approach, hence more enigmatic than land birds, at home in environments life-threatening to us. They were also uniquely disturbing to Audubon, the book’s editors Christoph Irmscher and Richard J. King argue, in their sheer abundance. They claim Audubon had no previous experience of such massive flocks, darkening the sky and crowding every inch of their breeding grounds, their guano heaped up like snow, filling the air with their deafening cries and vile stench. So there is a wry twist in the title’s phrase “at sea” (i.e., lost or confused) and in the subtitle’s “Adventures” (as if they were light-hearted!), which turn out to be—especially toward the end—when the story ventures into arctic waters and the terra incognita of Labrador—stories of seasickness, horrific gales, desolate wilderness, relentless rain and cold, with everything made worse by the depredations of men.

The focus of Audubon at Sea is indicated by its subtitle: The Coastal and Transatlantic Adventures of John James Audubon. It argues that he was never so comfortable at sea as he was on land when “collecting”—i.e., shooting—his specimens. Seabirds were harder to see up close, we are told; they are more elusive and maddening to approach, hence more enigmatic than land birds, at home in environments life-threatening to us. They were also uniquely disturbing to Audubon, the book’s editors Christoph Irmscher and Richard J. King argue, in their sheer abundance. They claim Audubon had no previous experience of such massive flocks, darkening the sky and crowding every inch of their breeding grounds, their guano heaped up like snow, filling the air with their deafening cries and vile stench. So there is a wry twist in the title’s phrase “at sea” (i.e., lost or confused) and in the subtitle’s “Adventures” (as if they were light-hearted!), which turn out to be—especially toward the end—when the story ventures into arctic waters and the terra incognita of Labrador—stories of seasickness, horrific gales, desolate wilderness, relentless rain and cold, with everything made worse by the depredations of men.

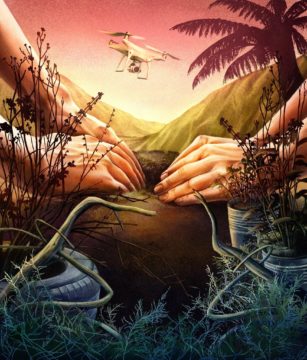

Eleanor Catton’s third novel, “Birnam Wood,” is a big book, a sophisticated page-turner, that does something improbable: It filters anarchist, monkey-wrenching environmental politics, a generational (anti-baby boomer) cri de coeur and a downhill-racing plot through a Stoppardian sense of humor. The result is thrilling. “Birnam Wood” nearly made me laugh with pleasure. The whole thing crackles, like hair drawn through a pocket comb.

Eleanor Catton’s third novel, “Birnam Wood,” is a big book, a sophisticated page-turner, that does something improbable: It filters anarchist, monkey-wrenching environmental politics, a generational (anti-baby boomer) cri de coeur and a downhill-racing plot through a Stoppardian sense of humor. The result is thrilling. “Birnam Wood” nearly made me laugh with pleasure. The whole thing crackles, like hair drawn through a pocket comb. During the first century of our era, the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca wrote to his friend Lucilius that life would be much happier if things would only decline as slowly as they grow. Unfortunately, as Seneca noted, “increases are of sluggish growth but the way to ruin is rapid.” We may call this universal rule the Seneca effect. Seneca’s idea that “ruin is rapid” touches something deep in our minds. Ruin, which we may also call “collapse,” is a feature of our world. We experience it with our health, our job, our family, our investments. We know that when ruin comes, it is unpredictable, rapid, destructive, and spectacular. And it seems to be impossible to stop until everything that can be destroyed is destroyed.

During the first century of our era, the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca wrote to his friend Lucilius that life would be much happier if things would only decline as slowly as they grow. Unfortunately, as Seneca noted, “increases are of sluggish growth but the way to ruin is rapid.” We may call this universal rule the Seneca effect. Seneca’s idea that “ruin is rapid” touches something deep in our minds. Ruin, which we may also call “collapse,” is a feature of our world. We experience it with our health, our job, our family, our investments. We know that when ruin comes, it is unpredictable, rapid, destructive, and spectacular. And it seems to be impossible to stop until everything that can be destroyed is destroyed. Whenever I’m feeling uninspired, I think: Somewhere, somebody is doing something right now. You may say this sounds less like a hype mantra and more like the mother of all mediocre movie taglines; you would not be wrong. Nevertheless, this thought is, for me, a surefire poem-generator—lifting me up, up, and away from the well-worn facticity of myself, out into the contemporaneous “Mysteries” of unknown others and their unknown lives.

Whenever I’m feeling uninspired, I think: Somewhere, somebody is doing something right now. You may say this sounds less like a hype mantra and more like the mother of all mediocre movie taglines; you would not be wrong. Nevertheless, this thought is, for me, a surefire poem-generator—lifting me up, up, and away from the well-worn facticity of myself, out into the contemporaneous “Mysteries” of unknown others and their unknown lives. From squabbling over who booked a disaster holiday to differing recollections of a glorious wedding, events from deep in the past can end up being misremembered. But now researchers say even recent memories may contain errors.

From squabbling over who booked a disaster holiday to differing recollections of a glorious wedding, events from deep in the past can end up being misremembered. But now researchers say even recent memories may contain errors. In the US and around the world, people are

In the US and around the world, people are  I remember attending a symposium on space science in Washington, DC, sometime in the 1990s, at which the head of NASA at the time, Dan Goldin, gave a keynote address. He marched up to the podium in his trademark cowboy boots, looked out at the assembled astronomers and physicists in the audience, and asked: “How many biologists are here today?” No hands went up. He then said, “The next time I address this audience, I expect it to be full of biologists!”

I remember attending a symposium on space science in Washington, DC, sometime in the 1990s, at which the head of NASA at the time, Dan Goldin, gave a keynote address. He marched up to the podium in his trademark cowboy boots, looked out at the assembled astronomers and physicists in the audience, and asked: “How many biologists are here today?” No hands went up. He then said, “The next time I address this audience, I expect it to be full of biologists!”