Sharanya Deepak in The Baffler:

Sharanya Deepak in The Baffler:

WHEN JUNAID KHAN was a young boy, his mother, Saira Begum, would return home close to nightfall. She would squat next to an open fire to cook rotis for her hungry son, who would smear them with butter. “Junaid would eat rotis in whole gulps. I had to stop him before he ate too much,” Saira told me one summer evening in 2019. She lives with her relatives in a small brick house in Khandawali, a village in Haryana near New Delhi. When we spoke, she lay on her divan. In a corner stood a desk on which Junaid would study. Like many women in her village, Saira is a farm laborer whose income—four thousand rupees per month in 2019, or fifty-seven dollars—does not ensure food for her family at all times. She owns one buffalo, however, that she milks and uses to plow the land that she works. Food is scarce in her home, but the white butter she made with buffalo milk was delicious and filling for her children.

Junaid was sixteen years old when he, his older brother Hashim, and two friends were attacked on a train in Haryana in June 2017. The boys were commuting home from an Eid shopping trip and a visit to the mosque when they were asked to vacate their seats by a group of men. When I visited Saira’s home, Hashim explained that the men noticed they were Indian Muslims and threatened to beat them if they didn’t move. “They were older, larger, and Hindu,” he recounted, as he fiddled with a photograph of Junaid. “They kept calling us beef eaters,” he continued, along with other faith-based slurs.

More here.

Imagine if you went outside and saw that it had started to rain, and that people on the street were opening their umbrellas. And imagine that you ran around waving your arms and saying “Stop! Stop! Umbrellas make rain worse!!” People would think you were a silly person, and rightly so.

Imagine if you went outside and saw that it had started to rain, and that people on the street were opening their umbrellas. And imagine that you ran around waving your arms and saying “Stop! Stop! Umbrellas make rain worse!!” People would think you were a silly person, and rightly so.

Sharanya Deepak in The Baffler:

Sharanya Deepak in The Baffler:

Ewald Engelen in Sidecar:

Ewald Engelen in Sidecar: I

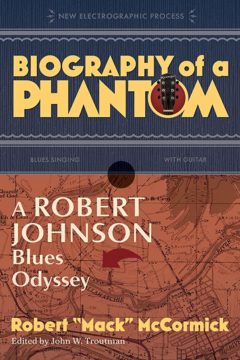

I The Robert Johnson we meet in this book remains somewhat blurry and indistinct. He wasn’t a big personality, people tell McCormick. He was soft-spoken; he held people’s attention only when he played.

The Robert Johnson we meet in this book remains somewhat blurry and indistinct. He wasn’t a big personality, people tell McCormick. He was soft-spoken; he held people’s attention only when he played. One of the stultifying but ultimately true maxims of the analytics movement in sports says that most narratives around player performance are lies. Each player has a “

One of the stultifying but ultimately true maxims of the analytics movement in sports says that most narratives around player performance are lies. Each player has a “ Those who don’t already admire Hardwick’s writing likely know her from her marriage to poet Robert Lowell. It is at times a lurid story. A masterful poet, Lowell was also bipolar at a time when treatment was (as it still can be for many) uncertain and inconsistent. During manic episodes, he could be cruel to his wife. (“Everybody has noticed that you’ve been getting pretty dumb lately,” he told her during one episode.) While she worked to keep their household together, ensure bills were paid, and oversee his care, he would call her family to tell them he never loved her. His mania often coincided with brazen affairs; friends, colleagues, and even doctors sometimes suspected Hardwick of jealousy when she tried to get him help. When he finally left her after 20 years of marriage, he wrote a collection of poems—dedicated to his new wife, Caroline Blackwood—that excerpted his ex-wife’s plaintive letters to him and (perhaps the worse betrayal) fabricated others without noting the difference. The Dolphin was condemned by friends like Elizabeth Bishop and Adrienne Rich, but it also won the National Book Award. (In a published review, Rich called the book “one of the most vindictive and mean-spirited acts in the history of poetry.”) Years later, Lowell and Hardwick reconciled. Visiting her in New York not long after, he took a taxi from the airport and died before arriving. Summoned by the cab driver, Hardwick rode alongside Lowell to the hospital, knowing that he was already dead.

Those who don’t already admire Hardwick’s writing likely know her from her marriage to poet Robert Lowell. It is at times a lurid story. A masterful poet, Lowell was also bipolar at a time when treatment was (as it still can be for many) uncertain and inconsistent. During manic episodes, he could be cruel to his wife. (“Everybody has noticed that you’ve been getting pretty dumb lately,” he told her during one episode.) While she worked to keep their household together, ensure bills were paid, and oversee his care, he would call her family to tell them he never loved her. His mania often coincided with brazen affairs; friends, colleagues, and even doctors sometimes suspected Hardwick of jealousy when she tried to get him help. When he finally left her after 20 years of marriage, he wrote a collection of poems—dedicated to his new wife, Caroline Blackwood—that excerpted his ex-wife’s plaintive letters to him and (perhaps the worse betrayal) fabricated others without noting the difference. The Dolphin was condemned by friends like Elizabeth Bishop and Adrienne Rich, but it also won the National Book Award. (In a published review, Rich called the book “one of the most vindictive and mean-spirited acts in the history of poetry.”) Years later, Lowell and Hardwick reconciled. Visiting her in New York not long after, he took a taxi from the airport and died before arriving. Summoned by the cab driver, Hardwick rode alongside Lowell to the hospital, knowing that he was already dead. May, by contrast, the elusive

May, by contrast, the elusive  It was a source of some annoyance to Charles Portis that Shakespeare never wrote about Arkansas. As the novelist pointed out, it wasn’t, strictly speaking, impossible: Hernando de Soto had ventured to the area in 1541, members of his expedition wrote about their travels in journals that were translated into English, and at least one of those accounts was circulating in London when Shakespeare was working there in 1609. To Portis, it was also perfectly obvious that the exploration of his home state could have been fine fodder for the Bard: “It is just the kind of chronicle he quarried for his plots and characters, and DeSoto, a brutal, devout, heroic man brought low, is certainly of Shakespearean stature. But, bad luck, there is no play, with a scene at the Camden winter quarters, and, in another part of the forest, at Smackover Creek, where willows still grow aslant the brook.”

It was a source of some annoyance to Charles Portis that Shakespeare never wrote about Arkansas. As the novelist pointed out, it wasn’t, strictly speaking, impossible: Hernando de Soto had ventured to the area in 1541, members of his expedition wrote about their travels in journals that were translated into English, and at least one of those accounts was circulating in London when Shakespeare was working there in 1609. To Portis, it was also perfectly obvious that the exploration of his home state could have been fine fodder for the Bard: “It is just the kind of chronicle he quarried for his plots and characters, and DeSoto, a brutal, devout, heroic man brought low, is certainly of Shakespearean stature. But, bad luck, there is no play, with a scene at the Camden winter quarters, and, in another part of the forest, at Smackover Creek, where willows still grow aslant the brook.” At 53, Suga Free still looks exactly like Suga Free. Honoring his commandment to be fly for life, his hair remains long and luxurious. He’s draped in a custom-made tracksuit with his name emblazoned on the back. The right questions elicit stanzas of profane one-liners, flamboyant slang and coldblooded wisdom. (“Every time I walk out of my house and turn that key in my car, that means I’m finna spend some money,” he laughs. “I’m trying to squeeze a quarter till the eagle screams.”) Ask the wrong question and you don’t want the answer.

At 53, Suga Free still looks exactly like Suga Free. Honoring his commandment to be fly for life, his hair remains long and luxurious. He’s draped in a custom-made tracksuit with his name emblazoned on the back. The right questions elicit stanzas of profane one-liners, flamboyant slang and coldblooded wisdom. (“Every time I walk out of my house and turn that key in my car, that means I’m finna spend some money,” he laughs. “I’m trying to squeeze a quarter till the eagle screams.”) Ask the wrong question and you don’t want the answer. It’s coming. Winds are weakening along the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Heat is building beneath the ocean surface. By July,

It’s coming. Winds are weakening along the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Heat is building beneath the ocean surface. By July,  It might feel pretty obvious to you that you’re weak-willed. You feel it, after all – every time you find yourself hitting the snooze button on the alarm when you know you ought to get out of bed; every time you scroll through cat videos on Instagram when you know you ought to be writing; every time you help yourself to a third slice of cake when you know you ought to order a kale smoothie instead. When you find yourself in these situations, there’s often a bit of shame, a bit of guilt, a bit of frustration. In many cases, the subsequent conviction that we’re weak-willed shapes our entire approach to motivating ourselves.

It might feel pretty obvious to you that you’re weak-willed. You feel it, after all – every time you find yourself hitting the snooze button on the alarm when you know you ought to get out of bed; every time you scroll through cat videos on Instagram when you know you ought to be writing; every time you help yourself to a third slice of cake when you know you ought to order a kale smoothie instead. When you find yourself in these situations, there’s often a bit of shame, a bit of guilt, a bit of frustration. In many cases, the subsequent conviction that we’re weak-willed shapes our entire approach to motivating ourselves.