Rob Stein on NPR:

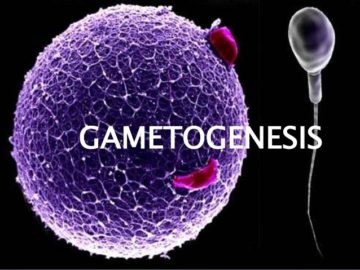

Researchers are inching closer to mass-producing eggs and sperm in the lab from ordinary human cells. The technique could provide new ways to treat infertility but also open a Pandora’s box.

Researchers are inching closer to mass-producing eggs and sperm in the lab from ordinary human cells. The technique could provide new ways to treat infertility but also open a Pandora’s box.

ROB STEIN, BYLINE: It’s a Wednesday morning at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in downtown Washington, D.C.

ELI ADASHI: Welcome, everybody, to the National Academy of Medicine workshop.

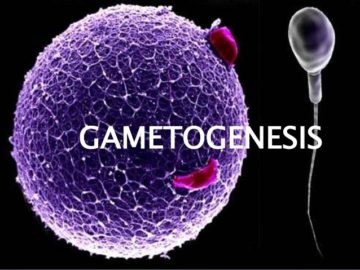

STEIN: Dr. Eli Adashi from Brown University opens the Academy’s first gathering to explore the latest scientific developments and complicated social implications of something known as in vitro gametogenesis, or IVG, which involves making human eggs and sperm in the laboratory from any cell in a person’s body.

ADASHI: It is on the precipice of materialization, and IVF will probably never be the same.

STEIN: Japanese scientists describe how they’ve already done this in mice, coaxing cells from the tails of adult mice to become what’s known as induced pluripotent stem cells, or IPS cells, and then coaxing those cells to become mouse sperm and eggs. They’ve even used those sperm and eggs to make embryos and implanted the embryos into the wombs of female mice, which gave birth to apparently healthy mouse pups. Mitinori Saitou joins the workshop via Zoom from Kyoto University.

More here.

The great French writer Colette once speculated that “certain highly complex human beings” are marked by their “mental hermaphroditism.” The fabled essayist Susan Sontag was among them. She was a woman, but she dressed in the glamorously genderless garb of an intellectual celebrity and wrote on the weighty topics usually reserved for her male peers. In her journals, she mused that “to be an intellectual is to be attached to the inherent value of plurality.”

The great French writer Colette once speculated that “certain highly complex human beings” are marked by their “mental hermaphroditism.” The fabled essayist Susan Sontag was among them. She was a woman, but she dressed in the glamorously genderless garb of an intellectual celebrity and wrote on the weighty topics usually reserved for her male peers. In her journals, she mused that “to be an intellectual is to be attached to the inherent value of plurality.” When

When  Researchers are inching closer to mass-producing eggs and sperm in the lab from ordinary human cells. The technique could provide new ways to treat infertility but also open a Pandora’s box.

Researchers are inching closer to mass-producing eggs and sperm in the lab from ordinary human cells. The technique could provide new ways to treat infertility but also open a Pandora’s box. After 35 years of living in relative control of my decisions, I had decided to see what would happen if I asked AI to control my life instead. Years of suboptimal performance, both personally and professionally, and numerous failed attempts at self-improvement had convinced me there had to be a better way, and I wondered if the collective knowledge hidden inside OpenAI’s hit tech product could help me. But when I asked Sam Altman’s ChatGPT to become my all-powerful leader, it seemed reticent, at least at first.

After 35 years of living in relative control of my decisions, I had decided to see what would happen if I asked AI to control my life instead. Years of suboptimal performance, both personally and professionally, and numerous failed attempts at self-improvement had convinced me there had to be a better way, and I wondered if the collective knowledge hidden inside OpenAI’s hit tech product could help me. But when I asked Sam Altman’s ChatGPT to become my all-powerful leader, it seemed reticent, at least at first. A new generation of drugs is revolutionizing the treatment of obesity and

A new generation of drugs is revolutionizing the treatment of obesity and  Coming up with economic policy is a difficult, unforgiving task. To make the best of it, it helps to work with an accurate model of how the economy works. If you use a misleading model and act on it, you can’t reasonably expect good outcomes: in that scenario, we end up, as JM Keynes warned in the 1930s, with “madmen in authority”, acting according to the precepts of “some defunct economist”.

Coming up with economic policy is a difficult, unforgiving task. To make the best of it, it helps to work with an accurate model of how the economy works. If you use a misleading model and act on it, you can’t reasonably expect good outcomes: in that scenario, we end up, as JM Keynes warned in the 1930s, with “madmen in authority”, acting according to the precepts of “some defunct economist”. W

W I like when the refs touch each other in any way, but especially when all three of them put their arms around one another, huddling to discuss a difficult call. I like watching endless replays of fouls, trying to decide whether something was a block or a charge, or who touched the ball last. I like when the commentators disagree with the refs and when the broadcast cuts to the former ref Steve Javie in some NBA warehouse in New Jersey, standing in front of TV screens, calmly hypothesizing what the refs are discussing.

I like when the refs touch each other in any way, but especially when all three of them put their arms around one another, huddling to discuss a difficult call. I like watching endless replays of fouls, trying to decide whether something was a block or a charge, or who touched the ball last. I like when the commentators disagree with the refs and when the broadcast cuts to the former ref Steve Javie in some NBA warehouse in New Jersey, standing in front of TV screens, calmly hypothesizing what the refs are discussing. 1.

1.  In the twenties, Archie League was spinning, diving, and doing loop-the-loops above the clouds, engine roaring, little plane shaking as he and the other barnstormers in his flying circus entertained folks across Missouri and Illinois. Necks grew stiff from watching, eyes squinted against the light, jaws dropped and air rushing in with every oooohhhh and whoa and oh my sweet Lord Jesus.

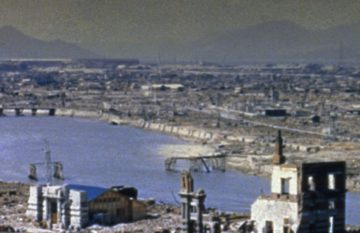

In the twenties, Archie League was spinning, diving, and doing loop-the-loops above the clouds, engine roaring, little plane shaking as he and the other barnstormers in his flying circus entertained folks across Missouri and Illinois. Necks grew stiff from watching, eyes squinted against the light, jaws dropped and air rushing in with every oooohhhh and whoa and oh my sweet Lord Jesus. Amid the carnage of the Second World War, which saw some 60 million killed, including the Nazis’ industrialized annihilation of six million Jews, one event stands out in American memory as the most momentous: the atomic bomb attack that leveled Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. According to the most authoritative Japanese casualty count, which is higher than the American figure, the bomb killed some 100,000 people outright and another 40,000 over the next several months; blast, flash burns, and firestorm took care of the former, and radiation sickness accounted for the latter. A second bomb that dropped just three days later on Nagasaki killed 70,000 all told but gave some people misgivings even more troubling than those produced by Hiroshima.

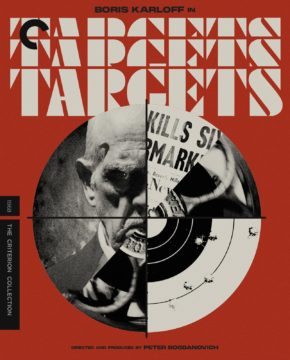

Amid the carnage of the Second World War, which saw some 60 million killed, including the Nazis’ industrialized annihilation of six million Jews, one event stands out in American memory as the most momentous: the atomic bomb attack that leveled Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. According to the most authoritative Japanese casualty count, which is higher than the American figure, the bomb killed some 100,000 people outright and another 40,000 over the next several months; blast, flash burns, and firestorm took care of the former, and radiation sickness accounted for the latter. A second bomb that dropped just three days later on Nagasaki killed 70,000 all told but gave some people misgivings even more troubling than those produced by Hiroshima. While Bogdanovich was about as immersed in cinema as is possible, a key inspiration for his 1968 debut, Targets—a thriller whose terse, nightmarish qualities would not be repeated across his wide-ranging and influential filmography—came not from the movies but from real life. Charles Whitman was an altar boy, an Eagle Scout, a marine, and a mass murderer: in 1966, between the last day of July and the first day of August, the twenty-five-year-old ex–bank teller killed sixteen people—including his wife and mother—and wounded more than thirty others, shooting the majority of his victims from the observation deck of the Main Building of the University of Texas at Austin. For the mass media, which made him a household name—“The Psychotic and Society,” declared a Time cover featuring his image—he was a cleaner-cut cousin to Lee Harvey Oswald, his sights trained not on political power or celebrity but on the everyday citizens whom he resembled at a distance, and maybe under the skin as well. “I don’t really understand myself these days,” the shooter himself observed in the half-typed, half-handwritten suicide note discovered at his residence. “I am supposed to be an average reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I can’t recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts.”

While Bogdanovich was about as immersed in cinema as is possible, a key inspiration for his 1968 debut, Targets—a thriller whose terse, nightmarish qualities would not be repeated across his wide-ranging and influential filmography—came not from the movies but from real life. Charles Whitman was an altar boy, an Eagle Scout, a marine, and a mass murderer: in 1966, between the last day of July and the first day of August, the twenty-five-year-old ex–bank teller killed sixteen people—including his wife and mother—and wounded more than thirty others, shooting the majority of his victims from the observation deck of the Main Building of the University of Texas at Austin. For the mass media, which made him a household name—“The Psychotic and Society,” declared a Time cover featuring his image—he was a cleaner-cut cousin to Lee Harvey Oswald, his sights trained not on political power or celebrity but on the everyday citizens whom he resembled at a distance, and maybe under the skin as well. “I don’t really understand myself these days,” the shooter himself observed in the half-typed, half-handwritten suicide note discovered at his residence. “I am supposed to be an average reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I can’t recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts.” It began as an urbane fable about how to brush down bristling nerves. Sometime in the summer of 1909, not long before Sigmund Freud was due to embark on his only visit to the United States, he was enjoying a cigar in the company of his inner circle in the busy Biedermeier interior of Berggasse 19, when he suddenly announced, “I am going to America to catch sight of a wild porcupine and to give some lectures.”

It began as an urbane fable about how to brush down bristling nerves. Sometime in the summer of 1909, not long before Sigmund Freud was due to embark on his only visit to the United States, he was enjoying a cigar in the company of his inner circle in the busy Biedermeier interior of Berggasse 19, when he suddenly announced, “I am going to America to catch sight of a wild porcupine and to give some lectures.”