The Bell

We always praise what’s praisable

with imperfection

understood in the overtones.

When we say we’re free

we mean more or less –

always too much less, probably.

When we say our country’s great

we mean – as others have said about theirs –

such as it is, based on us.

Us – each of whom

by all he himself has chosen

stands not as tall as he’d like to stand.

Governing men have lied,

so have I, so have you, lied,

among many other things.

Our greed and fraud are broadcast.

Jefferson thinks it’ll all work out;

John Adams has doubts.

The iron tongue of that bell

will ring and bong and clang and sing

a complicated song.

It’s physical tone shall sound pure,

like the communication of angels;

but we’ll know (won’t we?)

what’s going on, who’s pulling

together on the rope underneath:

a man, a woman: both,

among other things, Americans.

by R.P.Dickey

—thanks to Nils Peterson

John Dewey

John Dewey In theory, Nate works 40 hours a week in the operations department at a major fintech company. In reality, Nate works one hour a day at most. He moseys over to his computer whenever he gets an alert on his phone that he’s got a task to complete. Otherwise, he spends most of the day doing, basically, whatever he feels — he sleeps in, he watches TV, he does household chores. His only real restriction is that he can’t stray too far from home in the event he is needed for something.

In theory, Nate works 40 hours a week in the operations department at a major fintech company. In reality, Nate works one hour a day at most. He moseys over to his computer whenever he gets an alert on his phone that he’s got a task to complete. Otherwise, he spends most of the day doing, basically, whatever he feels — he sleeps in, he watches TV, he does household chores. His only real restriction is that he can’t stray too far from home in the event he is needed for something. Spanning from 1900 to 1977 in Kerala, The Covenant of Water reveals some of the contradictions of living in a colonised, segregated society. Dr Digby Kilgour, the lonely son of an impoverished alcoholic mother, flees Scotland for colonised India, only to discover that he is “oppressed in Glasgow; oppressor here. The thought depresses him.” Yet the complicated questions that might develop as he negotiates with those increasingly fraught realities are set aside while he contends with his new hospital job and begins an affair with a woman who is married to a colleague. Tensions rise as that colleague makes a fatal medical error and places the blame on Digby. Any confrontation that would have occurred, however, is derailed by an accident that conveniently pushes Digby’s storyline in another direction.

Spanning from 1900 to 1977 in Kerala, The Covenant of Water reveals some of the contradictions of living in a colonised, segregated society. Dr Digby Kilgour, the lonely son of an impoverished alcoholic mother, flees Scotland for colonised India, only to discover that he is “oppressed in Glasgow; oppressor here. The thought depresses him.” Yet the complicated questions that might develop as he negotiates with those increasingly fraught realities are set aside while he contends with his new hospital job and begins an affair with a woman who is married to a colleague. Tensions rise as that colleague makes a fatal medical error and places the blame on Digby. Any confrontation that would have occurred, however, is derailed by an accident that conveniently pushes Digby’s storyline in another direction. As trees and flowers blossom in spring, bees emerge from their winter nests and burrows. For many species it’s

As trees and flowers blossom in spring, bees emerge from their winter nests and burrows. For many species it’s  “Jaffa will be a Jewish city … Allowing Arabs to return to Jaffa would not be righteousness but stupidity,” David Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary in June 1948.

“Jaffa will be a Jewish city … Allowing Arabs to return to Jaffa would not be righteousness but stupidity,” David Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary in June 1948. A group of small children sits cross-legged with their teacher, Steve Mejía-Menendez, on a round carpet. He’s a pre-K teacher at Lee Montessori Public Charter School’s campus in Southeast Washington, D.C., and although I’m here to meet him, I almost don’t spot him because he’s eye level with his students.

A group of small children sits cross-legged with their teacher, Steve Mejía-Menendez, on a round carpet. He’s a pre-K teacher at Lee Montessori Public Charter School’s campus in Southeast Washington, D.C., and although I’m here to meet him, I almost don’t spot him because he’s eye level with his students. There is a mental-health crisis in science — at all career stages and across the world. Graduate students are being

There is a mental-health crisis in science — at all career stages and across the world. Graduate students are being  There was no immediate indication of who might have created this amazing dress diary, as I called it—of who had spent so much time carefully arranging the pieces of wool, silk, cotton, and lace into a document of lives in cloth. While there was much I was uncertain of, however, one thing I knew for sure from the careful handwriting that arched over each piece of cloth: this was the work of one woman. I just didn’t know who she was.

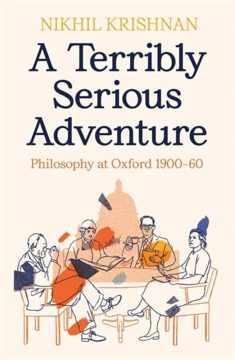

There was no immediate indication of who might have created this amazing dress diary, as I called it—of who had spent so much time carefully arranging the pieces of wool, silk, cotton, and lace into a document of lives in cloth. While there was much I was uncertain of, however, one thing I knew for sure from the careful handwriting that arched over each piece of cloth: this was the work of one woman. I just didn’t know who she was. Austin died in 1960, at the age of 48, and Krishnan sees this as the end of ordinary language philosophy. Metaphysical ambition – though still in the form of conceptual analysis – was exemplified by Strawson, who examined the basic structure of the human world, including our concept of persons, in Individuals: An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics (1959). Questions about the relation between mind and body had not been put to rest by Ryle; they remain wide open to this day. And moral and political theory flourished from the 1970s.

Austin died in 1960, at the age of 48, and Krishnan sees this as the end of ordinary language philosophy. Metaphysical ambition – though still in the form of conceptual analysis – was exemplified by Strawson, who examined the basic structure of the human world, including our concept of persons, in Individuals: An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics (1959). Questions about the relation between mind and body had not been put to rest by Ryle; they remain wide open to this day. And moral and political theory flourished from the 1970s. For many viewers, the highlight of Ken Burns’s documentary The Civil War is the reading of a poignant letter from a Union soldier to his wife a week before he is killed in the First Battle of Bull Run. “Sarah, my love for you is deathless,” Major Sullivan Ballou writes from his unit’s camp in Washington, DC. “It seems to bind me with mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence can break; and yet, my love of country comes over me like a strong wind, and bears me irresistibly on with all those chains to the battlefield.” Concluding the series’ premiere episode in September 1990, the letter became the equivalent of a viral phenomenon in that pre-social media age: “Within minutes of the first night’s broadcast,” Burns said a year later, “the phone began ringing off the hook with calls from across the country, eager to find out about Sullivan Ballou….The calls would not stop all week—and they continue.” The letter still resonates today—Senator Chuck Schumer read an excerpt at Donald Trump’s inauguration—and in multiple articles turned up by a Google search, the word that recurs most frequently to praise it is “eloquent.”

For many viewers, the highlight of Ken Burns’s documentary The Civil War is the reading of a poignant letter from a Union soldier to his wife a week before he is killed in the First Battle of Bull Run. “Sarah, my love for you is deathless,” Major Sullivan Ballou writes from his unit’s camp in Washington, DC. “It seems to bind me with mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence can break; and yet, my love of country comes over me like a strong wind, and bears me irresistibly on with all those chains to the battlefield.” Concluding the series’ premiere episode in September 1990, the letter became the equivalent of a viral phenomenon in that pre-social media age: “Within minutes of the first night’s broadcast,” Burns said a year later, “the phone began ringing off the hook with calls from across the country, eager to find out about Sullivan Ballou….The calls would not stop all week—and they continue.” The letter still resonates today—Senator Chuck Schumer read an excerpt at Donald Trump’s inauguration—and in multiple articles turned up by a Google search, the word that recurs most frequently to praise it is “eloquent.” The modern world is large and interconnected, and there are a lot of systems that might be important to how it functions but about which most people are barely aware. One of these is the offshore wealth management network, which wealthy individuals can use both legitimately (to invest and plan their money) and less legitimately (to avoid taxation or hide questionable practices generally). Brooke Harrington is a sociologist who has studied offshore wealth management, including by training to be one. In

The modern world is large and interconnected, and there are a lot of systems that might be important to how it functions but about which most people are barely aware. One of these is the offshore wealth management network, which wealthy individuals can use both legitimately (to invest and plan their money) and less legitimately (to avoid taxation or hide questionable practices generally). Brooke Harrington is a sociologist who has studied offshore wealth management, including by training to be one. In  The 1970s and 1980s are usually seen as the transformative era of recent American political history. And if the 1970s saw a

The 1970s and 1980s are usually seen as the transformative era of recent American political history. And if the 1970s saw a  “Drop me down anywhere in America and I’ll tell you where I am: in America.” Perhaps you need to be a slight stranger to this country to formulate American ubiquity in this way—as comic tautology, as wry Q.E.D. Quite often, in the last twenty years, I’ve found myself driving along some strip development in Massachusetts or New York State, or Indiana or Nevada for that matter, and as the repetitive commercial furniture passes by—the Hampton Inn, the kindergarten pink-and-orange of Dunkin’ Donuts, Chick-fil-A’s chirpy red rooster—I’m suddenly seized by panic, because for a second I don’t know where I am. The placeless wallpaper keeps unfurling. And then Martin Amis’s sentence from his great early book of journalism, “

“Drop me down anywhere in America and I’ll tell you where I am: in America.” Perhaps you need to be a slight stranger to this country to formulate American ubiquity in this way—as comic tautology, as wry Q.E.D. Quite often, in the last twenty years, I’ve found myself driving along some strip development in Massachusetts or New York State, or Indiana or Nevada for that matter, and as the repetitive commercial furniture passes by—the Hampton Inn, the kindergarten pink-and-orange of Dunkin’ Donuts, Chick-fil-A’s chirpy red rooster—I’m suddenly seized by panic, because for a second I don’t know where I am. The placeless wallpaper keeps unfurling. And then Martin Amis’s sentence from his great early book of journalism, “ Imagine a physicist observing a quantum system whose behavior is akin to a coin toss: it could come up heads or tails. They perform the quantum coin toss and see heads. Could they be certain that their result was an objective, absolute and indisputable fact about the world? If the coin was simply the kind we see in our everyday experience, then the outcome of the toss would be the same for everyone: heads all around! But as with most things in quantum physics, the result of a quantum coin toss would be a much more complicated “It depends.” There are theoretically plausible scenarios in which another observer might find that the result of our physicist’s coin toss was tails.

Imagine a physicist observing a quantum system whose behavior is akin to a coin toss: it could come up heads or tails. They perform the quantum coin toss and see heads. Could they be certain that their result was an objective, absolute and indisputable fact about the world? If the coin was simply the kind we see in our everyday experience, then the outcome of the toss would be the same for everyone: heads all around! But as with most things in quantum physics, the result of a quantum coin toss would be a much more complicated “It depends.” There are theoretically plausible scenarios in which another observer might find that the result of our physicist’s coin toss was tails.