Category: Archives

A Saint For Ordinary People

John Rodden at Commonweal:

The key to Philip’s personal appeal was his humor. As a boy, his favorite reading had been a famous joke book by a fellow Florentine, Arlotto Mainardi. As a man, Philip was quite a jester—and very jolly as well as a little zany. Writing about Philip in his Italian Journey, Goethe dubbed him “the humorous saint.”

The key to Philip’s personal appeal was his humor. As a boy, his favorite reading had been a famous joke book by a fellow Florentine, Arlotto Mainardi. As a man, Philip was quite a jester—and very jolly as well as a little zany. Writing about Philip in his Italian Journey, Goethe dubbed him “the humorous saint.”

But it wasn’t just that Philip liked a good joke. He radiated joy, a kind of elevated bonhomie. In Mystic in Motley: The Life of Saint Philip Neri, Theodore Maynard reports that Philip would burst suddenly into song at Mass. Fearing he might swoon at the altar with ecstatic fervor, he would direct his altar boys to read aloud his favorite jokes from Mainardi’s book, to bring him back down to earth so that he could concentrate on the ritual tasks at hand. But even this wasn’t always enough to calm him for long. We are told that, as he read the Passion during Holy Week, Philip would play with his keys and spin a sundial placed near the altar in order to help him keep his composure.

more here.

On Kenneth Anger’s ‘Fireworks’ (1947)

Ars Osterweil at Artforum:

Germany Year Zero is the closest that Italian Neorealism came to reckoning with the psychic life of children. Made at the same time, Fireworks meditates on the generative possibilities of psychic and sexual shattering. In so many ways, Fireworks anticipates the explosion of the queer underground cinema that blossomed in the United States in the ’60s and in which Anger’s later film Scorpio Rising (1963) played a central role. Yet Fireworks is also a product of its own “queer time and place.”

Germany Year Zero is the closest that Italian Neorealism came to reckoning with the psychic life of children. Made at the same time, Fireworks meditates on the generative possibilities of psychic and sexual shattering. In so many ways, Fireworks anticipates the explosion of the queer underground cinema that blossomed in the United States in the ’60s and in which Anger’s later film Scorpio Rising (1963) played a central role. Yet Fireworks is also a product of its own “queer time and place.”

In a famous quip, Anger described Fireworks as all he had “to say about being 17, The United States Navy, American Christmas and The Fourth of July.” When the film begins, we see his body draped, pietà-like, in a sailor’s arms. The film cuts to a close-up of Anger’s face as he sleeps, followed by shots of his nude torso, hands, and what appears to be a massive erection, but which turns out, in Eisensteinian fashion, to be a phallic African totem. A plaster cast of a hand with missing fingers inaugurates the film’s fascination with besieged corporeality. As in most dream narratives, we suspect that the dreamer has merely imagined himself in the sailor’s arms.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Yard Sale in Mid-April

A briefcase

where he stored grandfather’s papers, an abacus,

then a fake gold clock with two bells on its head, an old barbeque

for inside-the-house cooking, about the size of a three-layer cake,

a pencil from Russia with a green tip for sketching, the sky is above

all this, not in a religious sense, it notes this delight I take on rare

occasions, then it continues its own miracles, it does not matter

that I am not seeing things, matter, space, future, spirit,

all this does not matter, I step into the kitchen, give the abacus

to my niece, tell my daughter about my cooking, wander outside

under the clouds.

by Juan Filipe Herrera

from Half Of The World In Light

University of Arizona Press, 2008

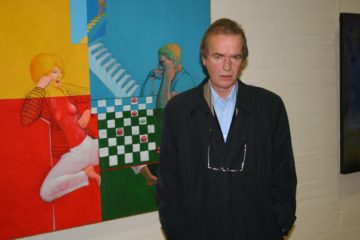

“The British Male!”: On Martin Amis

Lidija Haas in The Paris Review:

To be British is a very complicated fate. To be a British novelist can seem a catastrophe. You enter into a miasma of history and class and garbage and publication—the way a sad cow might feel entering the abattoir. Or certainly that was how I felt, twenty years ago, when I entered the abattoir myself. One allegory for this system was the glamour of Martin Amis. Everyone had an opinion on Amis, and the strangeness was that this opinion was never just on the prose, on the novels and the stories and the essays. It was also an opinion on his opinions: the party gossip and the newspaper theories, the Oxford education and the afternoon tennis.

To be British is a very complicated fate. To be a British novelist can seem a catastrophe. You enter into a miasma of history and class and garbage and publication—the way a sad cow might feel entering the abattoir. Or certainly that was how I felt, twenty years ago, when I entered the abattoir myself. One allegory for this system was the glamour of Martin Amis. Everyone had an opinion on Amis, and the strangeness was that this opinion was never just on the prose, on the novels and the stories and the essays. It was also an opinion on his opinions: the party gossip and the newspaper theories, the Oxford education and the afternoon tennis.

The British male! Or at least the British bourgeois male, with his many father figures, both real and acquired. From certain angles, in certain photos, Amis looked like Jagger, and so he became the Jagger of literature. He was small, true—I feel a permanent pang of camaraderie at his line in The Pregnant Widow about a character who occupies that “much-disputed territory between five foot six and five foot seven”—but he was also hypermasculine. It wasn’t just his subjects: the snooker and the booze and the obsession with judging all women “sack artists.” It wasn’t even just the style: an inability to leave a sentence alone without chafing at every verb, the prose equivalent of truffle fries. It was also the interview persona, all haughtiness and clubhouse universality, however much that could be contradicted in private by thoughtfulness and generosity of conversation.

More here.

Memories Help Brains Recognize New Events Worth Remembering

Yasemin Sapalakoglu in Quanta Magazine:

Memories are shadows of the past but also flashlights for the future. Our recollections guide us through the world, tune our attention and shape what we learn later in life. Human and animal studies have shown that memories can alter our perceptions of future events and the attention we give them. “We know that past experience changes stuff,” said Loren Frank, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco. “How exactly that happens isn’t always clear.”

Memories are shadows of the past but also flashlights for the future. Our recollections guide us through the world, tune our attention and shape what we learn later in life. Human and animal studies have shown that memories can alter our perceptions of future events and the attention we give them. “We know that past experience changes stuff,” said Loren Frank, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco. “How exactly that happens isn’t always clear.”

A new study published in the journal Science Advances now offers part of the answer. Working with snails, researchers examined how established memories made the animals more likely to form new long-term memories of related future events that they might otherwise have ignored. The simple mechanism that they discovered did this by altering a snail’s perception of those events. The researchers took the phenomenon of how past learning influences future learning “down to a single cell,” said David Glanzman, a cell biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles who was not involved in the study. He called it an attractive example “of using a simple organism to try to get understanding of behavioral phenomena that are fairly complex.”

More here.

Sunday, May 28, 2023

Anglo-Calvinist moralism has turned the American arts into something strenuously polite and deadly dull

William Deresiewicz in Tablet:

I’m bored; you’re bored; we’re all bored. By our books and movies and television shows, the endless blandness of the Netflix queue, by our music and theater and art. Culture now is strenuously cautious, nervously polite, earnestly worthy, ploddingly obvious, and above all, dismally predictable. It never dares to stray beyond the four corners of the already known. Robert Hughes spoke of the shock of the new, his phrase for modernism in the arts. Now there’s nothing that is shocking, and nothing that is new: irresponsible, dangerous; singular, original; the child of one weird, interesting brain. Decent we have, sometimes even good: well-made, professional, passing the time. But wild, indelible, commanding us without appeal to change our lives? I don’t think we even remember what that feels like.

I’m bored; you’re bored; we’re all bored. By our books and movies and television shows, the endless blandness of the Netflix queue, by our music and theater and art. Culture now is strenuously cautious, nervously polite, earnestly worthy, ploddingly obvious, and above all, dismally predictable. It never dares to stray beyond the four corners of the already known. Robert Hughes spoke of the shock of the new, his phrase for modernism in the arts. Now there’s nothing that is shocking, and nothing that is new: irresponsible, dangerous; singular, original; the child of one weird, interesting brain. Decent we have, sometimes even good: well-made, professional, passing the time. But wild, indelible, commanding us without appeal to change our lives? I don’t think we even remember what that feels like.

What accounts for this?

More here.

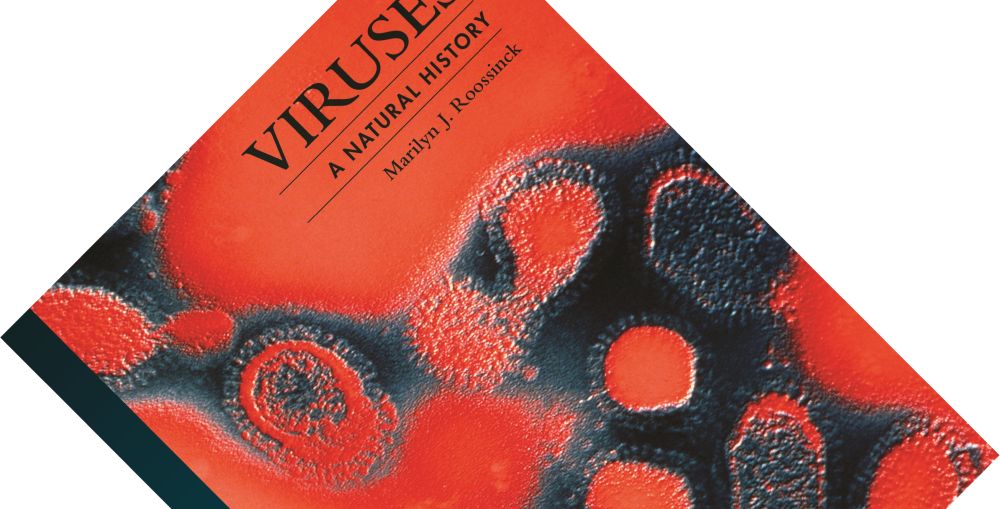

Book Review – Viruses: A Natural History

Leon Vlieger in The Inquisitive Biologist:

Viruses are possibly even more maligned than bacteria, spoken of exclusively in terms of disease. Here, virologist Marilyn J. Roossinck ranges far beyond human pathogens to convince you how narrow that picture is. She instead reveals them as enigmatic entities that are intimately entwined with the entirety of Earth’s biosphere, exploiting and enabling it in equal measure. Backed by numerous infographics, the book alternates between chapters on basic principles of virology and brief portraits of noteworthy viruses. The result is an entry-level introduction to virology that fascinated me more than I expected.

Viruses are possibly even more maligned than bacteria, spoken of exclusively in terms of disease. Here, virologist Marilyn J. Roossinck ranges far beyond human pathogens to convince you how narrow that picture is. She instead reveals them as enigmatic entities that are intimately entwined with the entirety of Earth’s biosphere, exploiting and enabling it in equal measure. Backed by numerous infographics, the book alternates between chapters on basic principles of virology and brief portraits of noteworthy viruses. The result is an entry-level introduction to virology that fascinated me more than I expected.

More here.

A road trip across the cradle of civilisation

Simon Urwin in BBC:

“This is not a scenic drive,” said James Willcox, of adventure travel specialist Untamed Borders. “But what’s incredible about Route 1 is where it takes you: to the birthplace of some of the world’s earliest civilisations, the home of many of humankind’s greatest innovations.”

“This is not a scenic drive,” said James Willcox, of adventure travel specialist Untamed Borders. “But what’s incredible about Route 1 is where it takes you: to the birthplace of some of the world’s earliest civilisations, the home of many of humankind’s greatest innovations.”

Willcox, who was charged with logistics and security for my journey, was briefing me before I embarked on a 530km, two-day road trip from Basra to Baghdad. My trip would be using Iraq’s first and longest freeway, the 1,200km-long Route 1, as a conduit to explore the heart of ancient Mesopotamia. Though the region has experienced decades of recent conflict, it was also once home to a series of illustrious historical empires (the Babylonians, Assyrians and Sumerians to name a few), and Willcox reassured me that the journey would be unforgettable so long as I followed some simple rules: “Keep a low profile, dress conservatively and don’t photograph any of the armed checkpoints,” he said.

I flew into Basra, Iraq’s largest port. The city straddles the Shatt al-Arab river, which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates – the two mighty waterways that inspired the name Mesopotamia (meaning “between two rivers” in Greek).

More here.

Cannes and the banality of evil

Alissa Wilkinson in Vox:

At the press conference following the Cannes premiere of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, someone asked Robert De Niro about his character, a kingpin of a sort with a tricky psyche. “It’s the banality of evil,” he said, describing the character’s moral ambiguity. “It’s the thing we have to watch out for. We see it today, of course. We all know who I’m going to talk about, but I’m not going to say his name.” (Everyone knew who he meant.)

At the press conference following the Cannes premiere of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, someone asked Robert De Niro about his character, a kingpin of a sort with a tricky psyche. “It’s the banality of evil,” he said, describing the character’s moral ambiguity. “It’s the thing we have to watch out for. We see it today, of course. We all know who I’m going to talk about, but I’m not going to say his name.” (Everyone knew who he meant.)

The banality of evil was hot at Cannes this year. De Niro’s statement came on the heels of the premiere of Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, which set Cannes critics abuzz about the same phrase. That movie — which I proposed might best be understood as an adaptation of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, even more than the Martin Amis novel it’s loosely based on — is not much like Killers of the Flower Moon, at first blush. Glazer’s is short, taut horror that evokes the Holocaust by keeping it offscreen; Scorsese’s is epic, bloody, and relentless in its depiction of a series of murders from a century ago.

Thematically, however, they often rhyme. Both are about mankind’s ability to exterminate one another while deluding themselves into thinking they’re doing the right thing. Both are about atrocities so heinous they’re hard to wrap your mind around. And both feel eerily contemporary, in an age where prejudice, racism, and fascism are on the rise around the globe.

More here.

Sunday Poem

The Book of Lies

I’d like to have a word

with you. Could we be alone

for a minute? I have been lying

until now. Do you believe

I believe myself? Do you believe

yourself when you believe me? Lying

is natural. Forgive me. Could we be alone

forever? Forgive us all. The word

is my enemy. I have never been alone;

bribes, betrayals. I am lying

even now. Can you believe

that? I give you my word.

by James Tate

from Strong Measures

Harper Collins, 1986

Kenneth Anger (1927 – 2023) Experimental Filmmaker

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IgnRr170ERM&ab_channel=LibraryVHSRips

Tina Turner (1939 – 2023) Queen of Rock ‘n’ Roll

Martin Amis (1949 – 2023) Writer

Saturday, May 27, 2023

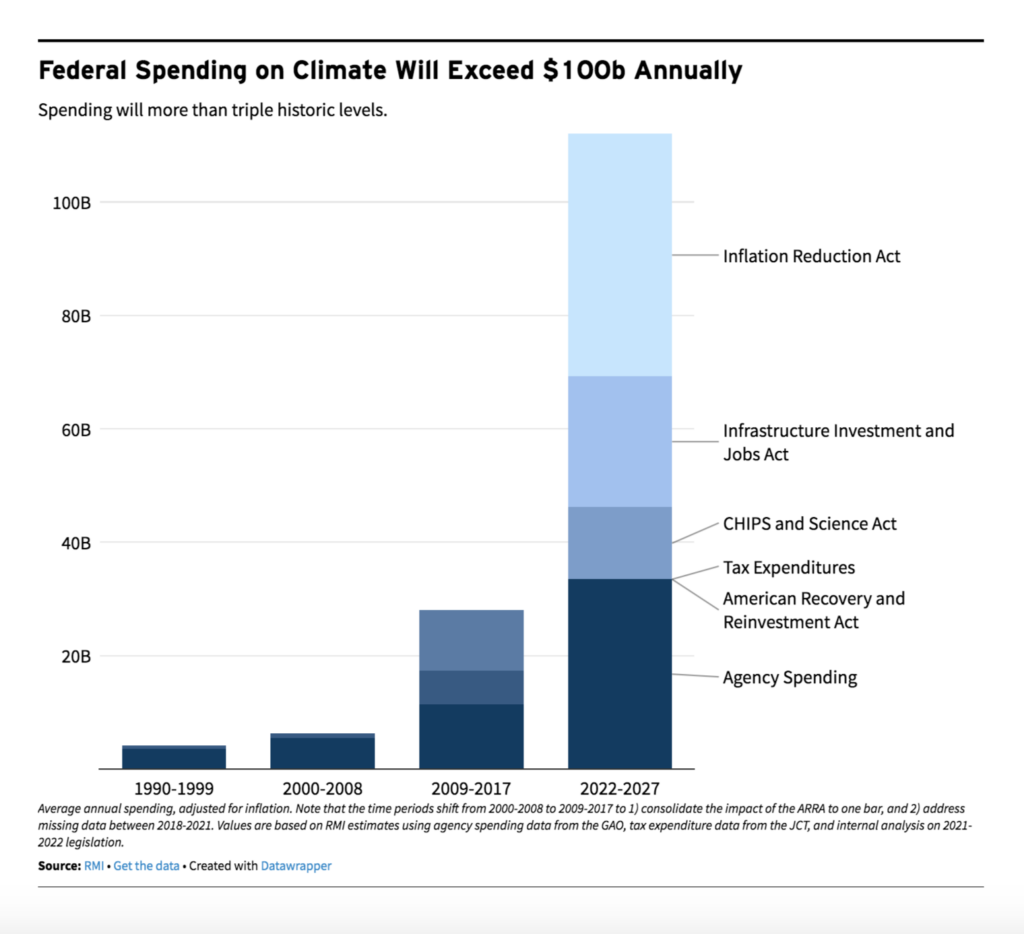

Green Industrial Strategy

Lachlan Carey in Phenomenal World:

Biden’s green industrial strategy is both impressive in scale and in its passage amidst highly complex political circumstances. After fractious negotiations, Congress authorized over $4 trillion in new investment between its four major pieces of economic legislation. Officially, around $500 billion of that spending goes towards climate-related spending, most of which is contained in the Inflation Reduction Act. According to our estimates, the US federal government will spend an average of over $100 billion each year on climate mitigation over the next ten years, about two and a half times the annual average from 2009-2017.

Even this figure is likely a significant underestimate. Since many of the tax credits contained in IRA are uncapped, total public expenditure is limited only by private demand for these incentives. If deployment of key clean energy technologies, such as solar or green hydrogen, were to be in line with a 2050 net-zero pathway, we estimate that total spending in the IRA alone could reach $1 trillion. A recent Brookings analysis reached a similar figure even without the net-zero constraint. This discrepancy is particularly large in renewable energy spending, which could see twice as much spending in a climate-aligned pathway—green hydrogen could see five times the spending, and the electric vehicle (EV) supply chain a staggering ten times the official Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates if consumers rush to buy cheaper EVs.

More here.

Non-Identity Crisis

Stephen Mulhall in the London Review of Books:

Stephen Mulhall in the London Review of Books:

For David Edmonds, and for many other philosophers, Derek Parfit, who died in 2017, was one of the greatest moral thinkers of the past century, perhaps even since John Stuart Mill. Edmonds rightly believes that if Parfit’s ideas about personal identity, rationality and equality were absorbed into our moral and political thinking, they would radically alter our beliefs about punishment, the distribution of social resources, our relationship to future generations, and more. So it’s easy to see why he wants to make Parfit’s ideas more widely known outside the academy. What is less easy to understand is his belief that the best, or even an appropriate, way of achieving this goal is to write a biography of him.

There was a time when biographies of philosophers weren’t just common, but expected and even required. Following Socrates, the great schools of Hellenistic philosophy (the Stoics, the Epicureans, the Neoplatonists) all tried to encourage the pursuit of a certain kind of life. For them, philosophy wasn’t primarily something you learned, but something you practised, with a view to self-transformation. So it was indispensable in critically evaluating a philosopher to critically evaluate their way of life, for that life was the definitive expression of their philosophy, and their writings were primarily a means of achieving that essential work on the self.

More here.

Is Equal Opportunity Enough?

A Boston Review Forum, with a lead piece by Christine Sypnowich:

A Boston Review Forum, with a lead piece by Christine Sypnowich:

The last decade has delivered increasingly bleak portraits of vast inequalities in income, wealth, health, and other measures of well-being in many rich capitalist countries, from the United States to the United Kingdom. What should we do about them?

One common response is to argue that inequalities are only a problem to the extent that they reflect unequal opportunities. Economist Jared Bernstein—a longtime advisor to Joe Biden, now a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers—expressed this view clearly in 2014 when he stated, “Opportunity and mobility are the right things to be talking about. . . . We always have inequality, and in America we’re not that upset about inequality of outcomes. But we are upset about inequality of opportunity.” Accordingly, in his first executive order as president, Biden proclaimed that “equal opportunity is the bedrock of American democracy.” For his part, British Labour leader Keir Starmer has stated his party’s aim should be to “pull down obstacles that limit opportunities and talent.” And Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has intoned that in Canada, where I live, “no matter who you are . . . you have every opportunity to live your life to its fullest potential.”

These statements are typical. In much of the West the tendency is to see equality as a matter of fairly distributed opportunities and to view an interest in outcomes as unreasonable, naïve, or even authoritarian. A similar focus on equality of opportunity is evident in the dominant strain of political philosophy in the Anglo-American world, liberal egalitarianism. In short, the prevailing political common sense tends to converge on the assumption that our egalitarian aspirations are realized once we have ensured equality of opportunity.

I think this view is seriously mistaken.

More here.

Tales of the tongue

Elizabeth Pennsi in Science:

Twice, quarterback Patrick Mahomes has led the Kansas City Chiefs to victory in the Super Bowl, the pinnacle of U.S. football. Although most fans have their eyes on the ball as Mahomes prepares to throw, his tongue does something just as interesting. Just as basketball star Michael Jordan did as he went up for a dunk, and dart players often do as they take aim for a bull’s-eye, Mahomes prepares to pass by sticking out his tongue. That may be more than a silly quirk, some scientists say. Those tongue protrusions may improve the accuracy of his hand movements.

Twice, quarterback Patrick Mahomes has led the Kansas City Chiefs to victory in the Super Bowl, the pinnacle of U.S. football. Although most fans have their eyes on the ball as Mahomes prepares to throw, his tongue does something just as interesting. Just as basketball star Michael Jordan did as he went up for a dunk, and dart players often do as they take aim for a bull’s-eye, Mahomes prepares to pass by sticking out his tongue. That may be more than a silly quirk, some scientists say. Those tongue protrusions may improve the accuracy of his hand movements.

A small but growing group of researchers is fascinated by an organ we often take for granted. We rarely think about how agile our own tongue needs to be to form words or avoid being bitten while helping us taste and swallow food. But that’s just the start of the tongue’s versatility across the animal kingdom. Without tongues, few if any terrestrial vertebrates could exist. The first of their ancestors to slither out of the water some 400 million years ago found a buffet stocked with new types of foods, but it took a tongue to sample them. The range of foods available to these pioneers broadened as tongues diversified into new, specialized forms—and ultimately took on functions beyond eating.

More here.

What’s the Point of Prizes?

Roger Rosenblatt in The New York Times:

Ah, the magical season of prizes is once again upon us. Each spring brings, along with warm rains and budding flowers, Fulbrights, Rhodeses, Pulitzers and Guggenheims, as well as Oscars, Tonys and Indies — which are thought of so fondly they come with their own nicknames. Everybody, it seems, loves honors and prizes. And they certainly make for great entertainment. The award ceremonies for literary prizes are usually demure, decorous little things, but award shows on TV are like a country music hoedown. And the Oscars rank so high in the culture that actors measure their worth by rehearsing their acceptance speeches.

Ah, the magical season of prizes is once again upon us. Each spring brings, along with warm rains and budding flowers, Fulbrights, Rhodeses, Pulitzers and Guggenheims, as well as Oscars, Tonys and Indies — which are thought of so fondly they come with their own nicknames. Everybody, it seems, loves honors and prizes. And they certainly make for great entertainment. The award ceremonies for literary prizes are usually demure, decorous little things, but award shows on TV are like a country music hoedown. And the Oscars rank so high in the culture that actors measure their worth by rehearsing their acceptance speeches.

Is there anything seriously wrong with all of this? Not that I can see. Winning a prize is an undeniably thrilling, magical thing. It is, in essence, the world’s way of telling you that you’ve done something noteworthy and valuable. It’s your moment to shine. But on the whole, do prizes do any good? Are they shallow or meaningful? Motivating or stultifying? Would the minds and achievements of Copernicus, Galileo, Vermeer or van Gogh have suffered chilling effects from winning prizes? What if Beethoven had squatted on his haunches after receiving a lifetime achievement award for his Fourth Symphony?

More here.

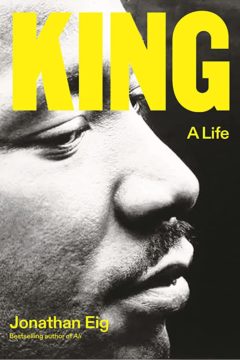

The Life of Martin Luther King

Kenneth W Mack at The Guardian:

Who was the Rev Martin Luther King Jr? In America, the civil rights activist and Baptist minister is now embraced across the political spectrum even as the teaching of the history of discrimination and segregation that shaped him is being actively suppressed in many parts of the country. Beyond the US, he is widely celebrated in nations confronting difficult questions about their own racial pasts.

Who was the Rev Martin Luther King Jr? In America, the civil rights activist and Baptist minister is now embraced across the political spectrum even as the teaching of the history of discrimination and segregation that shaped him is being actively suppressed in many parts of the country. Beyond the US, he is widely celebrated in nations confronting difficult questions about their own racial pasts.

At the time of his assassination in 1968, however, most Americans had a negative view of him, and the National Security Agency had tapped his overseas phone calls. As late as the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan could state that it was still an open question whether he had been a communist dupe, as King’s enemies at J Edgar Hoover’s FBI had long alleged. By the end of that decade, however, with a national holiday in his honour (reluctantly assented to by Reagan) and prize-winning biographies by Taylor Branch and David Garrow in print, King’s image had undergone a remarkable transformation.

more here.