Amy Kapczynski, Reshma Ramachandran and Christopher Morten in Boston Review:

Amy Kapczynski, Reshma Ramachandran and Christopher Morten in Boston Review:

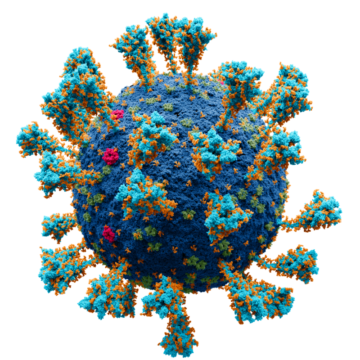

There have been no higher-stakes public investments recently than those the federal government made in biomedical research and production to make COVID-19 vaccines. Many commentators, conservatives and progressives alike, have seen the program that directed these investments, Operation Warp Speed (OWS), as a key example of how the government can enact new industrial policy—the deliberate attempt to shape different sectors of the economy to meet public aims. David Adler, for example, calls OWS “a triumph and validation of industrial policy,” concluding that the initiative “illustrates best practices in program design, as well as in government contracting” and should be a model for efforts to implement industrial strategy more broadly.

We think this view is seriously misguided. There is nothing new about industrial policy if it simply means public investments that yield vast benefits and outsized control for the private sector and comparatively little for the public. As historian Brent Cebul describes in his new book, Illusions of Progress, “supply-side liberalism”—a pattern of governance that directs federal money toward public aims but cedes critical aspects of policy, rules, and authority to the private sector—has a long history in the United States. In the late New Deal, ambitious federal spending programs like the Works Progress Administration gave significant control to local actors in order to overcome opposition of racist demagogues and business elites. This decentralized, deferential administrative model had staying power because it compensated for a lack of state capacity—and in turn, it helped ensure that no such capacity would be built. Cebul traces this template through the design of the postwar Federal Housing Administration and urban renewal into the 1980s and ’90s, when public-private partnerships and market-centered solutions became predominant during the Carter, Reagan, George H. Bush, and Clinton administrations.

The case of COVID-19 vaccines extends this pattern of political economy.

More here.