Cars in front of the train station of Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, during a brief but heavy snowfall last week.

Month: February 2024

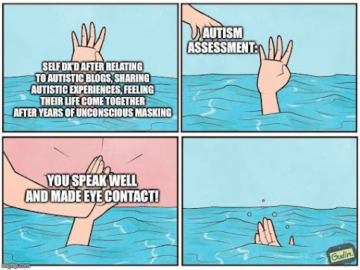

Perceptions of Autism

by Marie Snyder

There are a few ideas I’ve seen floating around on social media about people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) having no empathy, no Theory of Mind, and being in need of fixing instead of accommodating. I just ignored them. But then I heard similar statements in a university class with controversial Autism Speaks and Hopebridge videos on the curriculum. I relayed my concerns about promoting only these organizations without explanation of current concerns and without providing other perspectives like from the National Autistic Society or Autistic Self Advocacy Network. This is a bit of a take-down on what appears to be an accepted curriculum around autism.

There are a few ideas I’ve seen floating around on social media about people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) having no empathy, no Theory of Mind, and being in need of fixing instead of accommodating. I just ignored them. But then I heard similar statements in a university class with controversial Autism Speaks and Hopebridge videos on the curriculum. I relayed my concerns about promoting only these organizations without explanation of current concerns and without providing other perspectives like from the National Autistic Society or Autistic Self Advocacy Network. This is a bit of a take-down on what appears to be an accepted curriculum around autism.

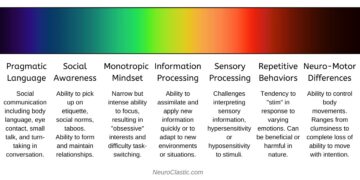

What is ASD? C.L. Lynch at NeuroClastic explains the spectrum really well using this illustration. You need to be affected in several of these areas regularly to be on the spectrum, and every person’s different. It’s complex. I went so far as to craft an assessment, the AQ-27, not remotely peer reviewed but rooted in the DSM-5, after being absolutely floored by the offensiveness or inaccuracy of the official assessments we had to learn in class.

What is ASD? C.L. Lynch at NeuroClastic explains the spectrum really well using this illustration. You need to be affected in several of these areas regularly to be on the spectrum, and every person’s different. It’s complex. I went so far as to craft an assessment, the AQ-27, not remotely peer reviewed but rooted in the DSM-5, after being absolutely floored by the offensiveness or inaccuracy of the official assessments we had to learn in class.

The Controversy:

Some advocates are “furious over the tone of the [Autism Speaks] video. ‘We don’t want to be portrayed as burdens or objects of fear and pity.” Hopebridge suffered scandals when an employee was fired for reporting an abusive incident with accounts of “undertrained staff and high turnover, a lack of transparency and accountability, and practices that prioritize profit over the needs and safety of young people with autism.” Some implications that people with ASD require lifelong care have been questioned since original stats were based on studies of children in psychiatric wards: “This potential bias means that we still know relatively little about the achievements of individuals in whom the presentation of early symptoms is more subtle.” Read more »

Western Metaphysics is Imploding. Will We Raise a Phoenix from The Ashes? [Catalytic AI]

I read a great deal of Bertrand Russell when I was in my teens. I read various collections of essays, such as Why I Am Not A Christian, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, and Marriage and Morals, some of which my father had stored in a box in the basement, along with Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, a book or two by this guy named Freud, though I forget which one, and some others. I also Russell’s – dare I say it? – magisterial A History of Western Philosophy And Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, which I purchase myself, a big thick paperback with a white cover. It was cited when he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950.

I read a great deal of Bertrand Russell when I was in my teens. I read various collections of essays, such as Why I Am Not A Christian, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, and Marriage and Morals, some of which my father had stored in a box in the basement, along with Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, a book or two by this guy named Freud, though I forget which one, and some others. I also Russell’s – dare I say it? – magisterial A History of Western Philosophy And Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, which I purchase myself, a big thick paperback with a white cover. It was cited when he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950.

It was from Russell more than anyone else that I got the idea that philosophy was a grand synthetic discipline, which I liked. Putting things together, seeing how all the parts interacted, that had immense appeal to me. And so I became a philosopher major when I enrolled in The Johns Hopkins University in 1965. I enjoyed an introductory course called, I believe, Types of Philosophy. Edward Lee’s course in Plato and the Pre-Socratics was wonderful as well; Lee was young, charismatic, and loved Mahler, as I did.

Then there was a two-semester sequence in the history of modern philosophy, from Descartes up through Kant. Maurice Mandelbaum taught the first semester, outlining each lecture on the board and then delivering on the outline. The lectures were so clear that you almost didn’t have to read the primary texts. The second semester was taught by a visitor from Chicago, Alan Gewirth. A different experience, like pulling teeth. Gewirth did the pulling and we students offered up our teeth. Ouch! But perhaps more pedagogically effective than Mandelbaum’s clarity, more Socratic, if you will.

By my junior year, however, I had come to realize that philosophy, as it is practiced in the academic world, is not what I had imagined it to be from reading Russell’s essay. It was another specialized discipline that had long ago abandoned any attempt at a broad synthesis. Fortunately, I had discovered literature, and Dr. Richard Macksey, whom I’ll discuss in more detail later. I’d always loved to read, and Macksey’s free-wheeling and broad ranging intellect appealed to me. I took four courses with him, plus an independent study on I forget what, and did a master’s thesis on “Kubla Khan” under his supervision. Literary criticism became the rubric under which I put things together. And why not? Literature expresses the world, and so couldn’t one study the world under the rubric of studying literature?

Well, no, if you must ask. By the time I’d figured that out – it didn’t take but a year or three – I was committed to an impossible intellectual project. I remain so committed. I will end this essay by arguing – it’s more of an earnest suggestion, really – that perhaps, if we do it right – of which there is no guarantee, and many signs that we’re botching it – we can harness these marvelous new machines to the job of synthesizing (human) knowledge. If we succeed, we’ll find ourselves in a whole new world, perhaps one where it is not at all obvious who is harnessed to what and to what end. I will, however, proceed indirectly. Read more »

US Media Is Collapsing, Here’s How to Save It

Alissa Quart at Jacobin:

The requests from independent journalists for grants, including personal emergency grants, have been coming in extra fast lately. Receiving them, me and my staff at the Economic Hardship Reporting Project feel like Lucille Ball grabbing the chocolates on the conveyor belt in that factory episode of I Love Lucy. The pace is picking up as publication closures and media layoffs push many into the world of full-time freelancing, where they compete for dwindling payouts against mounting competition. And as of last week, the Intercept, where my husband Peter Maass worked for ten years, has laid off fifteen of its staffers — including him. The media emergency just got even more personal.

The requests from independent journalists for grants, including personal emergency grants, have been coming in extra fast lately. Receiving them, me and my staff at the Economic Hardship Reporting Project feel like Lucille Ball grabbing the chocolates on the conveyor belt in that factory episode of I Love Lucy. The pace is picking up as publication closures and media layoffs push many into the world of full-time freelancing, where they compete for dwindling payouts against mounting competition. And as of last week, the Intercept, where my husband Peter Maass worked for ten years, has laid off fifteen of its staffers — including him. The media emergency just got even more personal.

Our family is far from alone. Sports Illustrated, formerly beefy with articles and bodacious with ads, has laid off its staff. Pitchfork, long my go-to for tart and encyclopedic endorsements or takedowns of music, has been folded, in a much-reduced form, into GQ — two media entities that, if they were people, would have never spoken to each other in high school. Meanwhile, the venerable Los Angeles Times announced it would be laying off at least 115 people, more than 20 percent of its staff.

More here.

The Growing Environmental Footprint Of Generative AI

David Berreby at Undark:

AI use is directly responsible for carbon emissions from non-renewable electricity and for the consumption of millions of gallons of fresh water, and it indirectly boosts impacts from building and maintaining the power-hungry equipment on which AI runs. As tech companies seek to embed high-intensity AI into everything from resume-writing to kidney transplant medicine and from choosing dog food to climate modeling, they cite many ways AI could help reduce humanity’s environmental footprint. But legislators, regulators, activists, and international organizations now want to make sure the benefits aren’t outweighed by AI’s mounting hazards.

More here.

Rebecca Solnit on the Perennial Divisions of the American Left

Rebecca Solnit at Literary Hub:

In late 1936 George Orwell, like so many young idealists from Europe and the USA, went off to fight fascism in Spain. By the spring of 1937 he realized he was in a war with not two but three sides. The USSR was holding back a full Spanish revolution while attacking the socialists and anarchists outside its control.

In late 1936 George Orwell, like so many young idealists from Europe and the USA, went off to fight fascism in Spain. By the spring of 1937 he realized he was in a war with not two but three sides. The USSR was holding back a full Spanish revolution while attacking the socialists and anarchists outside its control.

Facing prison and possible execution himself, not from the fascists, but the Soviet-allied forces, Orwell fled Spain. His immediate commander, Georges Kopp, was imprisoned, and the leader of his militia unit, Andres Nin, was tortured and assassinated by an agent of Stalin’s secret police. Orwell would spend the rest of his life trying to clarify that in his time the left meant both idealists committed to human rights, equality, and justice and supporters of a Stalinism that was the antithesis of all those things.

More here.

Disappearing tongues: the endangered language crisis

Ross Perlin in The Guardian:

Language is a universal and democratic fact cutting across all human societies: no human group is without it, and no language is superior to any other. More than race or religion, language is a window on to the deepest levels of human diversity. The familiar map of the world’s 200 or so nation-states is superficial compared with the little-known map of its 7,000 languages. Some languages may specialise in talking about melancholy, seaweed or atomic structure; some grammars may glory in conjugating verbs while others bristle with syntactic invention. Languages represent thousands of natural experiments: ways of seeing, understanding and living that should form part of any meaningful account of what it is to be human.

Language is a universal and democratic fact cutting across all human societies: no human group is without it, and no language is superior to any other. More than race or religion, language is a window on to the deepest levels of human diversity. The familiar map of the world’s 200 or so nation-states is superficial compared with the little-known map of its 7,000 languages. Some languages may specialise in talking about melancholy, seaweed or atomic structure; some grammars may glory in conjugating verbs while others bristle with syntactic invention. Languages represent thousands of natural experiments: ways of seeing, understanding and living that should form part of any meaningful account of what it is to be human.

More here.

I Am Not Your Negro

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

1959, the Year that Changed Jazz

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Jimmy Van Eaton (1937 – 2024) Hall of Fame Drummer

Damo Suzuki (1950 – 2024) Musician, Vocalist For Can

Roger Guillemin (1924 – 2024) Neuroscientist, Nobel Laureate

Sunday Poem

BLK History Month

If Black History Month is not

viable then the wind does not

carry the seeds and drop them

on fertile ground

rain does not

dampen the land

and encourage the seeds

to root

sun does not

warm the earth

and kiss the seedlings

and tell them plain:

You’re As Good A Anybody Else

You’ve Got A Place Here Too

by Nikki Giovanni

from Quilting The Black-Eyed Pea

Harper Perennial, 2002

Living in Arendt’s World

Blake Smith in The Ideas Letter:

Michael Denneny, the recently deceased co-founder and co-editor of the pioneering gay magazine Christopher Street , gay newspaper New York Native , and the gay publishing line at St. Martin’s Press, Stonewall Inn Editions, began his recently published collection of essays On Christopher Street with a quotation from his mentor, Hannah Arendt:

“Only in our speaking with one another does the world, as that about which we speak, emerge in its objectivity and visibility from all sides. Living in a real world and speaking with one another about it are basically one and the same.”

Denneny’s career as a gay cultural activist was a way of putting into practice Arendt’s thought as condensed in this citation. Across writings collected in On Christopher Street, which range in date from the beginnings of the magazine in 1976 to just before his death last year, he grounded his view of gay culture and politics in her work. Yet the importance of her example for their emergence—and of her philosophy to a key moment in the rise of what we now call “identity politics”—remains almost totally ignored in the field of gay history and in the ever-growing number of academic and popular reappraisals of Arendt. It is hardly known that her thinking and milieu were vital elements in intellectual matrix of the American gay movement.i

From academic and popular genealogies of gay identity and gay politics, whether written by progressive academics or conservatives pundits like Jamie Kirchick or Chris Rufo, readers could be forgiven for mistakenly believing misunderstanding that it was “radical” post-structuralist thinkers like Michel Foucault and Judith Butler who supplied that movement’s theoretical legitimation, resisted all the way by “mainstream” “assimilationists” (who are often portrayed by defenders and critics as anti-theoretical voices of “common sense”). Such genealogies misunderstand Foucault (who was much closer to the positions of Arendt and Denneny, an early champion of his, than to Butler and today’s “woke” activists)ii—although this is a subject for another essay. Moreover, they obscure the deep, and deeply Arendtian, thinking behind the cultural and political work that brought gay male life towards the center of American consciousness.

More here.

Why Hitch Still Matters: On Christopher Hitchens’s “A Hitch in Time”

Marius Sosnowski in LA Review of Books:

IT HAS BEEN 12 years since Christopher Hitchens left us. After his spirited showing in the 20th century, the first dozen years of the 21st were something of a reinvention. While Hitchens 2.0 may have left a trail of rubble in his wake, his books remained no less resolute than what had gone before: the vital study Why Orwell Matters (2002); the world-famous polemic God Is Not Great (2007); the best-selling and magisterial memoir Hitch-22 (2010); the compendious and ever-entertaining essay collection Arguably (2011); and his last feint from the edge of death, Mortality (2012). Still, it’s the belligerent terms of his late-in-life split from the Left that has threatened to eclipse a career dedicated to combating tribalist thinking, and fighting to illuminate the difference between what is and what is purported to be. One can’t help but feel a void, a conspicuous silence emanating from the direction of the Wyoming Apartments in Washington, DC, from which his rapier-like perceptions could have added something useful, even necessary, to the understanding of all that has followed.

Now, Twelve Books has published A Hitch in Time: Reflections Ready for Reconsideration, a welcome gathering of 23 mostly uncollected pieces he wrote for the London Review of Books (the volume was released in the United Kingdom in 2021 with an LRB-highlighting subtitle). With the exception of the opening essay, “The Wrong Stuff: On Tom Wolfe,” from 1983, and the closing one, “11 September 1973: Pinochet and Britain,” from 2002, everything herein dates from the 1990s, that thoroughly wacky and jaunty time everyone sorely misses. Hitchens is in memorable form here; his essays range from tackling P. G. Wodehouse, the First Gulf War, and the prevalence (nay, importance) of spanking to Britain’s social order, to the trouble with Bill Clinton, an almost sympathetic (or as close as Hitch could get to sympathy for a royal) portrait of the misunderstood Princess Margaret, and an evisceration of the United States’ charismatic hero JFK (and the comically jowly goons that followed in his presidential wake)—all while displaying the author’s characteristic impatience with courtiers, apologists, and tiresome bellends.

More here.

Shockwaves in the Global Order

Helena Cobban in Boston Review:

Just days before October 7, President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, was radiating confidence that Washington had effectively brought all of West Asia’s long-roiling conflicts under control. Washington could now, he believed, accelerate the pivot of attention, forces, and funding toward what had long topped Biden’s agenda: containing Chinese power in East Asia. Then came the Hamas-led attack on Israel and Israel’s onslaught on Gaza. By late January, Sullivan was flying to Bangkok to plead with top Chinese diplomat Wang Yi for help in defusing the sharp, Gaza-spurred conflict that had erupted in the globally vital waterway of the Red Sea. (Wang politely blew him off.)

Over the past four months, the United States has become increasingly isolated on the world stage. In October and again in November, the United States vetoed resolutions at the UN Security Council that called for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza on the grounds that they did not condemn Hamas. Then, on December 12, a special session of the UN General Assembly—where no country has veto power—voted 153 to 10, with 23 abstentions, in favor of a ceasefire resolution that made no mention of condemning Hamas. Those supporting the resolution included the BRICS group of nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), nearly all the other nations of the Global South, and some West European states, including France and Spain. The only states that joined the United States and Israel in voting against it were Austria, Czechia, Guatemala, Liberia, Paraguay, Papua New Guinea, and the tiny countries of Micronesia and Nauru.

More here.

The G20 Looks South

Bruno De Conti , Pedro Rossi, Arthur Welle, and Clara Saliba in Phenomenal World:

In December 2023, Brazil began presiding over the G20. The one-year presidency, which will culminate in the annual summit being hosted in Rio de Janeiro in November 2024, is the third of four terms from the global South—following Indonesia in 2022 and India in 2023, and preceding the already decided South African presidency in 2025. When India’s Narendra Modi formally handed over the presidency to Brazil last November, Lula announced three priorities to “place the reduction of inequalities at the center of the international agenda: (i) social inclusion and the fight against hunger (ii) energy transition and sustainable development in its three aspects (social, economic and environmental) and (iii) reform of global governance institutions.” The proposals were well received internationally; now is the time for concrete agendas to build toward the November summit.

Though the Brazilian government’s proposals are progressive, the G20’s multilateral dialogue continues within the context of international institutions that long predate it—reflecting the balance of global economic power in the middle of the twentieth century. Forged after World War II, institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, now undergird an international governance system that does not represent the tremendous changes that have occurred in the world economy since the fiscal rules they prescribed in the 1970s. Dominated by countries whose economies represent a shrinking share of world production and trade, these institutions reproduce asymmetries of power over the subjects of multilateral diplomacy—which are today indispensable for mitigating global climate change and extending social protections over the world’s economically and socially vulnerable populations.

The increased weight of the global South among countries making up the G20 indicates a changing balance of forces within the group—and shows how the moment is conducive for a shift in strategy. The group’s last summit in New Delhi illustrated the enhanced importance of the global South. Under the Indian presidency, this group of global South countries had at least two major victories representing the shift towards multipolarity: the absence of a unilateral position on the war in Ukraine and, more importantly, the inclusion of the African Union (AU) as a permanent member of the group.

More here.

Alphabetical Diaries By Sheila Heti

Hephzibah Anderson at The Guardian:

Canadian writer Sheila Heti’s 2010 breakout novel sought to interrogate its titular puzzler, How Should a Person Be? It’s become a continuing quest, but over the course of a career that now finds her publishing her 12th book, she’s also asked readers to consider again and again another question: how should prose be? Pairing philosophical inquiry with formal experimentation, she’s drawn inspiration from sources as scattered as reality TV, the I Ching and chatbot utterances, expanding our thinking about structure, character and the boundaries between fiction and memoir.

Canadian writer Sheila Heti’s 2010 breakout novel sought to interrogate its titular puzzler, How Should a Person Be? It’s become a continuing quest, but over the course of a career that now finds her publishing her 12th book, she’s also asked readers to consider again and again another question: how should prose be? Pairing philosophical inquiry with formal experimentation, she’s drawn inspiration from sources as scattered as reality TV, the I Ching and chatbot utterances, expanding our thinking about structure, character and the boundaries between fiction and memoir.

Both lines of investigation are furthered in this latest work, her most radical yet. It began when she decided to upload 10 years of her journal writing – 500,000 words in all – to an Excel spreadsheet, which ordered her sentences alphabetically.

more here.

Sheila Heti: Alphabetical Diaries w/ Lillian Fishman

The ‘Sad, Happy Life’ of Carson McCullers

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

“Carson McCullers: A Life” is a necessary book, though. It builds on Carr’s work and considers newly released material, including letters and journals and, most tantalizingly, transcripts of McCullers’s late-life psychiatric sessions with the female doctor who would become her lover and gatekeeper. It has been seven years since McCullers (1917-67) had her centennial, when the Library of America released her complete works in two volumes. That was an occasion, which many critics took, to revisit her work, which includes the novels “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter” (1940) and “The Member of the Wedding” (1946), and the story collection “The Ballad of the Sad Café” (1951).

“Carson McCullers: A Life” is a necessary book, though. It builds on Carr’s work and considers newly released material, including letters and journals and, most tantalizingly, transcripts of McCullers’s late-life psychiatric sessions with the female doctor who would become her lover and gatekeeper. It has been seven years since McCullers (1917-67) had her centennial, when the Library of America released her complete works in two volumes. That was an occasion, which many critics took, to revisit her work, which includes the novels “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter” (1940) and “The Member of the Wedding” (1946), and the story collection “The Ballad of the Sad Café” (1951).

Special notice was paid, and justly so, to McCullers’s gifts for portraying loners and misfits, for addressing taboo topics such as mental illness and alcoholism and same-sex relationships. As Joyce Carol Oates put it in The New York Review of Books, “McCullers seemed to have identified with whatever is trans- in the human psyche, seeing it as the very fuel of desire.”

more here.