Harmeet Kaur in CNN:

Blackface isn’t just about painting one’s skin darker or putting on a costume. It invokes a racist and painful history. The origins of blackface date back to the minstrel shows of mid-19th century. White performers darkened their skin with polish and cork, put on tattered clothing and exaggerated their features to look stereotypically “black.” The first minstrel shows mimicked enslaved Africans on Southern plantations, depicting black people as lazy, ignorant, cowardly or hypersexual, according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). The performances were intended to be funny to white audiences. But to the black community, they were demeaning and hurtful.

Blackface isn’t just about painting one’s skin darker or putting on a costume. It invokes a racist and painful history. The origins of blackface date back to the minstrel shows of mid-19th century. White performers darkened their skin with polish and cork, put on tattered clothing and exaggerated their features to look stereotypically “black.” The first minstrel shows mimicked enslaved Africans on Southern plantations, depicting black people as lazy, ignorant, cowardly or hypersexual, according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). The performances were intended to be funny to white audiences. But to the black community, they were demeaning and hurtful.

One of the most popular blackface characters was “Jim Crow,” developed by performer and playwright Thomas Dartmouth Rice. As part of a traveling solo act, Rice wore a burnt-cork blackface mask and raggedy clothing, spoke in stereotypical black vernacular and performed a caricatured song and dance routine that he said he learned from a slave, according to the University of South Florida Library.

Though early minstrel shows started in New York, they quickly spread to audiences in both the North and South. By 1845, minstrel shows spawned their own industry, NMAAHC says. Its influence extended into the 20th century. Al Jolson performed in blackface in “The Jazz Singer,” a hit film in 1927, and American actors like Shirley Temple, Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney put on blackface in movies too. The characters were so pervasive that even some black performers put on blackface, historians say. It was the only way they could work – as white audiences weren’t interested in watching black actors do anything but act foolish on stage.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

The mesmerizing performance from Academy Award-nominated actress and singer Andra Day in

The mesmerizing performance from Academy Award-nominated actress and singer Andra Day in  Panpsychism is the view that consciousness is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of the physical world. It is the view that the basic building blocks of the physical universe – perhaps fundamental particles – have incredibly simple forms of experience, and that the very sophisticated experience of the human or animal brain is rooted in, derived from, more rudimentary forms of experience at the level of basic physics. Panpsychism has received a lot of attention of late. The world of academic philosophy has been rocked by the conversion of one of the most influential materialists of the last thirty years, Michael Tye, to a form of panpsychism (

Panpsychism is the view that consciousness is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of the physical world. It is the view that the basic building blocks of the physical universe – perhaps fundamental particles – have incredibly simple forms of experience, and that the very sophisticated experience of the human or animal brain is rooted in, derived from, more rudimentary forms of experience at the level of basic physics. Panpsychism has received a lot of attention of late. The world of academic philosophy has been rocked by the conversion of one of the most influential materialists of the last thirty years, Michael Tye, to a form of panpsychism ( Throughout cinematic history, legendary Black actors have shattered barriers and

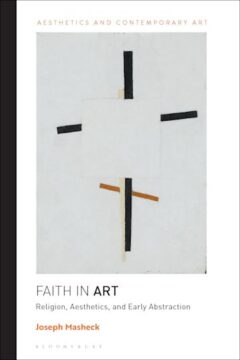

Throughout cinematic history, legendary Black actors have shattered barriers and  In the end, Faith in Art offers neither comprehensive views of these artists nor definitive conclusions about the religious bearings of their work. Nor is it concerned with establishing these artists’ faithful (or unfaithful) adherence to particular religious traditions—indeed, “none was religious in any conspicuous way.” Rather, Masheck seeks to show how “they believed that art had something formative to say about the possibility of a new, more humane society, by a faith ultimately based on scriptural, and sometimes surprisingly theological, intellectual formations.” This effectively pries open the critical histories of these artists, such that reducing these formations to either “materialism” or “spiritualism” becomes untenable.

In the end, Faith in Art offers neither comprehensive views of these artists nor definitive conclusions about the religious bearings of their work. Nor is it concerned with establishing these artists’ faithful (or unfaithful) adherence to particular religious traditions—indeed, “none was religious in any conspicuous way.” Rather, Masheck seeks to show how “they believed that art had something formative to say about the possibility of a new, more humane society, by a faith ultimately based on scriptural, and sometimes surprisingly theological, intellectual formations.” This effectively pries open the critical histories of these artists, such that reducing these formations to either “materialism” or “spiritualism” becomes untenable.

Evolution is sometimes described — not precisely, but with some justification — as being about the “survival of the fittest.” But that idea doesn’t work unless there is some way for one generation to pass down information about how best to survive. We now know that such information is passed down in a variety of ways: through our inherited genome, through epigenetic factors, and of course through cultural transmission. Chris Adami suggests that we update Dobzhansky’s maxim “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution” to “… except in the light of information.” We talk about information theory as a subject in its own right, and how it helps us to understand organisms, evolution, and the origin of life.

Evolution is sometimes described — not precisely, but with some justification — as being about the “survival of the fittest.” But that idea doesn’t work unless there is some way for one generation to pass down information about how best to survive. We now know that such information is passed down in a variety of ways: through our inherited genome, through epigenetic factors, and of course through cultural transmission. Chris Adami suggests that we update Dobzhansky’s maxim “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution” to “… except in the light of information.” We talk about information theory as a subject in its own right, and how it helps us to understand organisms, evolution, and the origin of life. Just days before October 7, President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, was radiating confidence that Washington had effectively brought all of West Asia’s long-roiling conflicts under control. Washington could now, he believed, accelerate the pivot of attention, forces, and funding toward what had long topped Biden’s agenda: containing Chinese power in East Asia. Then came the Hamas-led attack on Israel and Israel’s onslaught on Gaza. By late January, Sullivan was flying to Bangkok to plead with top Chinese diplomat Wang Yi for help in defusing the sharp, Gaza-spurred conflict that had erupted in the globally vital waterway of the Red Sea. (Wang politely blew him off.)

Just days before October 7, President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, was radiating confidence that Washington had effectively brought all of West Asia’s long-roiling conflicts under control. Washington could now, he believed, accelerate the pivot of attention, forces, and funding toward what had long topped Biden’s agenda: containing Chinese power in East Asia. Then came the Hamas-led attack on Israel and Israel’s onslaught on Gaza. By late January, Sullivan was flying to Bangkok to plead with top Chinese diplomat Wang Yi for help in defusing the sharp, Gaza-spurred conflict that had erupted in the globally vital waterway of the Red Sea. (Wang politely blew him off.) E

E The Oscars have never been about art. As Louis B. Mayer

The Oscars have never been about art. As Louis B. Mayer  The field of biology has driven remarkable advancements in medicine, agriculture, and industry over the last half-century, despite facing a significant hurdle: The immense complexity of biological systems makes them incredibly difficult to predict. This lack of predictability means that any innovation in biology requires many expensive trial-and-error experiments, inflating costs and slowing down progress in a wide range of applications, from drug discovery to biomanufacturing. But we are now at a critical inflection point in our ability to predict and engineer complex biological systems—transforming biology from a wet and messy science into an engineering discipline. This is being driven by the convergence of three major innovations: advancements in deep learning, significant cost reductions for collecting biological data through lab automation, and the precision editing of DNA with CRISPR.

The field of biology has driven remarkable advancements in medicine, agriculture, and industry over the last half-century, despite facing a significant hurdle: The immense complexity of biological systems makes them incredibly difficult to predict. This lack of predictability means that any innovation in biology requires many expensive trial-and-error experiments, inflating costs and slowing down progress in a wide range of applications, from drug discovery to biomanufacturing. But we are now at a critical inflection point in our ability to predict and engineer complex biological systems—transforming biology from a wet and messy science into an engineering discipline. This is being driven by the convergence of three major innovations: advancements in deep learning, significant cost reductions for collecting biological data through lab automation, and the precision editing of DNA with CRISPR.

Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou T

T