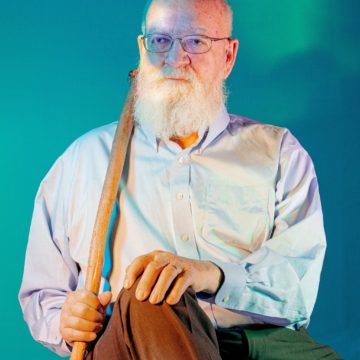

David Marchese in the New York Times:

For more than 50 years, Daniel C. Dennett has been right in the thick of some of humankind’s most meaningful arguments: the nature and function of consciousness and religion, the development and dangers of artificial intelligence and the relationship between science and philosophy, to name a few. For Dennett, an éminence grise of American philosophy who is nonetheless perhaps best known as one of the “four horsemen” of modern atheism alongside Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, there are no metaphysical mysteries at the heart of human existence, no magic nor God that makes us who we are. Instead, it’s science and Darwinian evolution all the way down. In his new memoir, “I’ve Been Thinking,” Dennett, a professor emeritus at Tufts University and author of multiple books for popular audiences, traces the development of his worldview, which he is keen to point out is no less full of awe or gratitude than that of those more inclined to the supernatural. “I want people to see what a meaningful, happy life I’ve had with these beliefs,” says Dennett, who is 81. “I don’t need mystery.”

For more than 50 years, Daniel C. Dennett has been right in the thick of some of humankind’s most meaningful arguments: the nature and function of consciousness and religion, the development and dangers of artificial intelligence and the relationship between science and philosophy, to name a few. For Dennett, an éminence grise of American philosophy who is nonetheless perhaps best known as one of the “four horsemen” of modern atheism alongside Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, there are no metaphysical mysteries at the heart of human existence, no magic nor God that makes us who we are. Instead, it’s science and Darwinian evolution all the way down. In his new memoir, “I’ve Been Thinking,” Dennett, a professor emeritus at Tufts University and author of multiple books for popular audiences, traces the development of his worldview, which he is keen to point out is no less full of awe or gratitude than that of those more inclined to the supernatural. “I want people to see what a meaningful, happy life I’ve had with these beliefs,” says Dennett, who is 81. “I don’t need mystery.”

More here.

If you infect a rabbit with a virus or a bacterium, it’ll start to run a fever. Why? The surprising answer is that fever is not a disease; it’s a defence: a useful evolved mechanism that

If you infect a rabbit with a virus or a bacterium, it’ll start to run a fever. Why? The surprising answer is that fever is not a disease; it’s a defence: a useful evolved mechanism that  I have never told this story in its entirety to anyone: not to my therapist, not to my closest friends, and not even to my family. I’ve divulged bits and pieces of it to different people. When my friends back home in Iran asked me why I was leaving, I made up a thousand different reasons. When my friends in Istanbul asked me what happened and why I came, I said that a part of me had died, that my ambition, courage, and hope for the future had dried up. But I didn’t explain why. I couldn’t connect the single moments into a coherent narrative.

I have never told this story in its entirety to anyone: not to my therapist, not to my closest friends, and not even to my family. I’ve divulged bits and pieces of it to different people. When my friends back home in Iran asked me why I was leaving, I made up a thousand different reasons. When my friends in Istanbul asked me what happened and why I came, I said that a part of me had died, that my ambition, courage, and hope for the future had dried up. But I didn’t explain why. I couldn’t connect the single moments into a coherent narrative. WHEN A DEER, A DOE, STEPPED INTO THE ROAD perhaps a hundred and twenty feet ahead of the car I was driving, it seemed for a moment that she would die, even though, during the same moment, I did not feel afraid that I would hit her. I was calm; I returned my smoking hand to the steering wheel; I braked. The deer seemed to be looking at me. There was a chance she might actually run toward me. I switched off the high-beams. All of this happened in two and a half seconds, before the deer continued across the road, safely to the other side, in a single bound. It was then that, exhaling, I realized the extent to which I had felt for—on behalf of—the animal, and for days after I dwelled on the feeling.

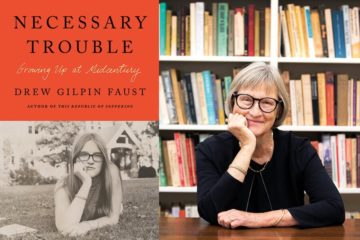

WHEN A DEER, A DOE, STEPPED INTO THE ROAD perhaps a hundred and twenty feet ahead of the car I was driving, it seemed for a moment that she would die, even though, during the same moment, I did not feel afraid that I would hit her. I was calm; I returned my smoking hand to the steering wheel; I braked. The deer seemed to be looking at me. There was a chance she might actually run toward me. I switched off the high-beams. All of this happened in two and a half seconds, before the deer continued across the road, safely to the other side, in a single bound. It was then that, exhaling, I realized the extent to which I had felt for—on behalf of—the animal, and for days after I dwelled on the feeling. Drew Gilpin Faust’s memoir is both a moving personal narrative and an enlightening account of the transformative political and social forces that impacted her as she came of age in the 1950s and ’60s. It’s an apt combination from an acclaimed historian who’s also a powerful storyteller.

Drew Gilpin Faust’s memoir is both a moving personal narrative and an enlightening account of the transformative political and social forces that impacted her as she came of age in the 1950s and ’60s. It’s an apt combination from an acclaimed historian who’s also a powerful storyteller. When the diabetes treatments known as GLP-1 analogs reached the market in 2005, doctors advised patients taking the drugs that they might lose a small amount of weight. Talk about an understatement. Obese people can drop more than 15% of their body weight, studies have found, and two of the medications are now approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for weight reduction. A surge in demand for the drugs as slimming treatments has led to shortages. “This class of drugs is exploding in popularity,” says clinical psychologist Joseph Schacht of the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

When the diabetes treatments known as GLP-1 analogs reached the market in 2005, doctors advised patients taking the drugs that they might lose a small amount of weight. Talk about an understatement. Obese people can drop more than 15% of their body weight, studies have found, and two of the medications are now approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for weight reduction. A surge in demand for the drugs as slimming treatments has led to shortages. “This class of drugs is exploding in popularity,” says clinical psychologist Joseph Schacht of the University of Colorado School of Medicine. In 1995, there weren’t many foreign tourists in the country. It was a year after the United States normalized relations with Hanoi and lifted sanctions. Most of the passengers on the flight to Hồ Chí Minh City were Việt kiều, visiting their country for the first time since they left. The tension they felt as they cleared customs was obvious.

In 1995, there weren’t many foreign tourists in the country. It was a year after the United States normalized relations with Hanoi and lifted sanctions. Most of the passengers on the flight to Hồ Chí Minh City were Việt kiều, visiting their country for the first time since they left. The tension they felt as they cleared customs was obvious. ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say

ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say  The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.