Month: August 2023

Monumental Mistakes

From Lapham’s Quarterly:

Writing to his uncle from quarantine in Rhodes, a twenty-eight-year-old Gustave Flaubert complained of the graffiti he had seen on Pompey’s pillar in Alexandria: an Englishman’s name carved in block letters. What right, Flaubert grumbled, did this man have to insert himself into other travelers’ experiences of the column? “Have you sometimes reflected, old uncle, on the limitless serenity of fools?” wrote the young novelist-to-be. “Stupidity is immovable…It has the nature of granite, hard and resistant.” According to him, the graffiti turned Pompey’s pillar into a monument not only to the Roman emperor Diocletian’s victory over a would-be usurper, but also to the foolishness of the public.

Writing to his uncle from quarantine in Rhodes, a twenty-eight-year-old Gustave Flaubert complained of the graffiti he had seen on Pompey’s pillar in Alexandria: an Englishman’s name carved in block letters. What right, Flaubert grumbled, did this man have to insert himself into other travelers’ experiences of the column? “Have you sometimes reflected, old uncle, on the limitless serenity of fools?” wrote the young novelist-to-be. “Stupidity is immovable…It has the nature of granite, hard and resistant.” According to him, the graffiti turned Pompey’s pillar into a monument not only to the Roman emperor Diocletian’s victory over a would-be usurper, but also to the foolishness of the public.

More here.

The 1963 March on Washington Changed America. Its Roots Were in Harlem

John Leland in The New York Times:

Sixty years ago, in the summer of 1963, a four-story townhouse on West 130th Street in Harlem became the headquarters for what was then the largest civil rights event in American history, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. For one summer the house, a former home for “delinquent colored girls,” was a hive of activity — so frenetic that the receptionist twice hung up on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by mistake. The march, which took place on Wednesday, Aug. 28, is now best remembered for Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and for the crowd of 250,000 filling the National Mall. But it would not have been possible without the organizing at 170 West 130th Street, led by Bayard Rustin, a brilliant tactician whose homosexuality and former communist ties made him a target both inside and outside the movement.

Sixty years ago, in the summer of 1963, a four-story townhouse on West 130th Street in Harlem became the headquarters for what was then the largest civil rights event in American history, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. For one summer the house, a former home for “delinquent colored girls,” was a hive of activity — so frenetic that the receptionist twice hung up on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by mistake. The march, which took place on Wednesday, Aug. 28, is now best remembered for Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and for the crowd of 250,000 filling the National Mall. But it would not have been possible without the organizing at 170 West 130th Street, led by Bayard Rustin, a brilliant tactician whose homosexuality and former communist ties made him a target both inside and outside the movement.

Under the aegis of the march’s patriarch, the labor leader A. Philip Randolph, Mr. Rustin brought together the heads of the five big civil rights organizations — the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, N.A.A.C.P., National Urban League, Congress of Racial Equality and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Together with Mr. Randolph, they became known as the Big Six. It was a pivotal moment in the civil rights movement, following Dr. King’s tumultuous campaign to force the desegregation of Birmingham and President John F. Kennedy’s sending the National Guard to enable Black students to attend the University of Alabama; Medgar Evers, a field secretary for the N.A.A.C.P., was assassinated in June in Mississippi. As Courtland Cox, one of the march organizers, recalled, “People were sick and tired of being sick and tired, and they wanted to make a statement to the nation.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

Human Chain

Seeing the bags of meal passed hand to hand

In close-up by the aid workers, and soldiers

Firing over the mob, I was braced again

With a grip on two sack corners,

Two packed wads of grain I’d worked to lugs

To give me purchase, ready for the heave—

The eye-to-eye, one-two, one-two upswing

On to the trailer, then the stoop and drag and drain

Of the next lift. Nothing surpassed

That quick unburdening, backbreak’s truest payback,

A letting go which will not come again.

Or it will, once. And for all.

by Seamus Heaney

from Human Chain

Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2010

How the Authors of the Bible Spun Triumph from Defeat

Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker:

The Moshiach came to Madison Avenue this summer. All over a not particularly Jewish neighborhood, posters of the bearded, Rembrandtesque Rebbe Schneerson appeared, mucilaged to every light post and bearing the caption “Long Live the Lubavitcher Rebbe King Messiah forever!” This was, or ought to have been, trebly astonishing. First, the rebbe being urged to a longer life died in 1994, and the new insistence that he was nonetheless the Moshiach skirted, as his followers tend to do, the question of whether he might remain somehow alive. Second, the very concept of a messiah recapitulates a specific national hope of a small and oft-defeated nation several thousand years ago, and spoke originally to the local Judaean dream of a warrior who would lead his people to victory over the Persians, the Greeks, and, latterly, the Roman colonizers. And, third, the disputes surrounding the rebbe from Crown Heights are strikingly similar to those which surrounded the rebbe Yeshua, or Jesus, when his followers first pressed his claim: was this messianic pretension a horrific blasphemy or a final fulfillment? Yet there it was, another Jewish messiah, on a poster, in 2023.

The Moshiach came to Madison Avenue this summer. All over a not particularly Jewish neighborhood, posters of the bearded, Rembrandtesque Rebbe Schneerson appeared, mucilaged to every light post and bearing the caption “Long Live the Lubavitcher Rebbe King Messiah forever!” This was, or ought to have been, trebly astonishing. First, the rebbe being urged to a longer life died in 1994, and the new insistence that he was nonetheless the Moshiach skirted, as his followers tend to do, the question of whether he might remain somehow alive. Second, the very concept of a messiah recapitulates a specific national hope of a small and oft-defeated nation several thousand years ago, and spoke originally to the local Judaean dream of a warrior who would lead his people to victory over the Persians, the Greeks, and, latterly, the Roman colonizers. And, third, the disputes surrounding the rebbe from Crown Heights are strikingly similar to those which surrounded the rebbe Yeshua, or Jesus, when his followers first pressed his claim: was this messianic pretension a horrific blasphemy or a final fulfillment? Yet there it was, another Jewish messiah, on a poster, in 2023.

The messianism on our street corners is a reminder of Judaism’s peculiarly long-lived legacy. Who can now tell Jupiter Dolichenus from Jupiter Optimus Maximus, two cult divinities once venerated at magnificent temples in Rome?

More here.

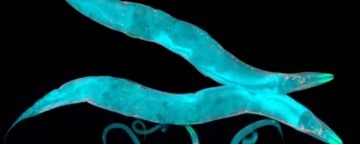

The Body, Not the Brain, Regulates Sleep

Rebecca Roberts in The Scientist:

Everyone knows about the importance of a good night’s sleep. Researchers have also shown the harmful effects of prolonged sleep deprivation on human health.1 Because the primary indicator of sleep is a loss of consciousness, and many of the ill effects from the lack of sleep associate with the brain, sleep researchers have naturally focused on neurons for sleep regulation studies.2

Everyone knows about the importance of a good night’s sleep. Researchers have also shown the harmful effects of prolonged sleep deprivation on human health.1 Because the primary indicator of sleep is a loss of consciousness, and many of the ill effects from the lack of sleep associate with the brain, sleep researchers have naturally focused on neurons for sleep regulation studies.2

Now, a new study published in Cell Reports has turned sleep research on its head. Researchers from the University of Tokyo and University of Tsukuba reported three key genes that are critical for regulating sleep—not in the brain, but in peripheral tissues.3 The findings demonstrate that sleep is all about protein homeostasis: endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and downregulation of protein biosynthesis in peripheral tissues trigger pathways that induce sleep. “For a long time, researchers have focused on studying sleep in the brain, but we found that the peripheral tissues are really requesting the brain to sleep,” said Yu Hayashi, a neuroscientist at the University of Tokyo and coauthor of the study. Given that prolonged wakefulness results in longer and deeper sleep, Hayashi hypothesized that there must be sleep-promoting substances that accumulate in the body during the time organisms are awake.

More here.

Pamela Sue Anderson: “Ethical Reflection and the Concept of “God:”

Essential Art

Louise Marburg at The Hudson Review:

I mean it as a compliment when I say many of the stories in The Islands are disturbing. Shame and alienation are the baggage Irving’s characters carry. Some are entitled, living the American dream, while others scrape by or are haunted by loss. “All-Inclusive” is a gorgeously dark story. In an ironic switch, Anaya, a Los Angeles model-slash-waitress and the daughter of Jamaican immigrants, meets a white man known as The Poet who is from Jamaica. Anaya becomes The Poet’s mistress, and they travel the world together. He is rich, she is poor; he is married, she is not. She revels in being able to “demand drinks, not deliver them,” and “To call for a bed to be turned down.” Anaya hasn’t visited Jamaica since she was a child, and her memories of the place are unpleasant. When she and The Poet take a trip to an all-inclusive resort on the island, Anaya wonders, had she been born and raised in Jamaica, if she would be doing the bidding of thoughtless white tourists, turning down their beds at night. She is ashamed and humbled by being waited on by people like herself and her family, many of whom still live on the island; that she is being willingly used by a white man who disgusts her is a truth she can’t admit to herself until he flat-out tells her. There are no happy endings in The Islands, and redemption is just out of reach. Its characters walk a tightrope between past and present realities.

I mean it as a compliment when I say many of the stories in The Islands are disturbing. Shame and alienation are the baggage Irving’s characters carry. Some are entitled, living the American dream, while others scrape by or are haunted by loss. “All-Inclusive” is a gorgeously dark story. In an ironic switch, Anaya, a Los Angeles model-slash-waitress and the daughter of Jamaican immigrants, meets a white man known as The Poet who is from Jamaica. Anaya becomes The Poet’s mistress, and they travel the world together. He is rich, she is poor; he is married, she is not. She revels in being able to “demand drinks, not deliver them,” and “To call for a bed to be turned down.” Anaya hasn’t visited Jamaica since she was a child, and her memories of the place are unpleasant. When she and The Poet take a trip to an all-inclusive resort on the island, Anaya wonders, had she been born and raised in Jamaica, if she would be doing the bidding of thoughtless white tourists, turning down their beds at night. She is ashamed and humbled by being waited on by people like herself and her family, many of whom still live on the island; that she is being willingly used by a white man who disgusts her is a truth she can’t admit to herself until he flat-out tells her. There are no happy endings in The Islands, and redemption is just out of reach. Its characters walk a tightrope between past and present realities.

more here.

Friday Poem

The Tao Begot One

The Tao begot one.

One begot two.

Two begot three.

And three begot the Ten Thousand Things.

The ten thousand things carry yin and embrace yang.

They achieve harmony by embracing these forces.

Men hate to be “orphaned,” widowed,” “worthless,”

But this is how kings and lords describe themselves.

For one gains by losing

And loses by gaining.

What others teach, I also teach; that is:

“A violent man will die a violent death!”

This will be the essence of my teaching.

Lao Tzu

from the Tao Te Ching

translation: Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English

Vintage Books, 1972

Art and Science as Parallel and Divergent Ways of Knowing

Lawrence Weschler at Wondercabinet:

Perhaps, to begin with, a remark by Nabokov—always a good place to start—who at the time was laying out the requisites for being a good novelist, though, for our purposes we might think of these as the requirements for being fully alive. But listen to him closely, because it’s the opposite of how we usually think of these things: “The true master,” he says, “requires, the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist.” The precision of a poet—and the imagination of a scientist.

Perhaps, to begin with, a remark by Nabokov—always a good place to start—who at the time was laying out the requisites for being a good novelist, though, for our purposes we might think of these as the requirements for being fully alive. But listen to him closely, because it’s the opposite of how we usually think of these things: “The true master,” he says, “requires, the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist.” The precision of a poet—and the imagination of a scientist.

Keep in mind, of course, that in some precincts, Nabokov was every bit as famous a scientist as he was a writer. A lepidopterist, to be exact, who once surprised his Italian publisher Roberto Calasso by telling him that he’d never been to Venice. “Good Lord,” asked Calasso. “Why ever not?” To which Nabokov answered, self-evidently, “No butterflies.”

more here.

The Fate of the Animals

J.C. Scharl at Fare Forward:

It’s hard to know how to review a Morgan Meis book, and the more books he writes, the harder it gets. That is, I think, precisely the point. Meis’s last book, The Drunken Silenus (part one of the Three Paintings trilogy, published by Slant Books), tackles the question “What is the best thing for man?”, knocks it flat, and gives it a concussion. Part two of the trilogy, The Fate of the Animals, is the tale of a painting whose artist thought it was almost unseeable, is enamored of the unsayable—yet by the final page, Meis has come terrifying close to saying just that.

It’s hard to know how to review a Morgan Meis book, and the more books he writes, the harder it gets. That is, I think, precisely the point. Meis’s last book, The Drunken Silenus (part one of the Three Paintings trilogy, published by Slant Books), tackles the question “What is the best thing for man?”, knocks it flat, and gives it a concussion. Part two of the trilogy, The Fate of the Animals, is the tale of a painting whose artist thought it was almost unseeable, is enamored of the unsayable—yet by the final page, Meis has come terrifying close to saying just that.

Morgan Meis is not everyone’s cup of tea, and The Fate of the Animals is the most Morgan Meis book yet. Take that as you will. For my part, I found the book shatteringly beautiful.

More here.

Allow patents on AI-generated inventions — for the good of science

Ryan Abbott in Nature:

AI’s contributions to research and development might help to solve some of humanity’s oldest challenges, including by finding new treatments for diseases. The patent system must be overhauled.

AI’s contributions to research and development might help to solve some of humanity’s oldest challenges, including by finding new treatments for diseases. The patent system must be overhauled.

An AI system is not a legal person, so it cannot (and should not) own property. Our cases have nothing to do with ‘AI rights’ — they are about what rules will maximize the social benefits of AI and minimize its risks.

The main purposes of the patent system are to encourage innovation, the disclosure of inventions that would otherwise be kept as trade secrets and the commercialization of new products. These outcomes could be achieved by allowing patent protection for AI-generated inventions, which would be owned by the AI’s owner, just as the owner of a 3D printer would also own what comes out of it.

More here.

Best Stephen Fry Moments on the Graham Norton Show

Why So Many Elites Feel Like Losers

Freddie deBoer in Persuasion:

The concept of “elite overproduction” has attracted a lot of attention in the past several years, and it’s not hard to see why. Most associated with Peter Turchin, a researcher who has attempted to develop models that describe and predict the flow of history, elite overproduction refers to periods during which societies generate more members of elite classes than the society can grant elite privileges. Turchin argues that these periods often produce social unrest, as the resentful elites jostle for the advantages to which they believe they’re entitled.

The concept of “elite overproduction” has attracted a lot of attention in the past several years, and it’s not hard to see why. Most associated with Peter Turchin, a researcher who has attempted to develop models that describe and predict the flow of history, elite overproduction refers to periods during which societies generate more members of elite classes than the society can grant elite privileges. Turchin argues that these periods often produce social unrest, as the resentful elites jostle for the advantages to which they believe they’re entitled.

Consider societies in which aristocrats enjoy feudal privileges over land and are afforded influence in government. These sorts of dynastic privileges have been common in world history. Now imagine that over time, the number of people in this class has grown; more and more children of aristocrats means there are more and more people who hold aristocratic status. This creates a math problem: there’s only so much land to divide up and only so many people that can meaningfully guide government.

More here.

Four Ways of Thinking – safety in numbers?

Steven Poole in The Guardian:

Depending on which source of pop-rationality you consult, there are three, five, six or more ways of thinking that need to be mastered before the psychology-entertainment complex will consider you “smart”. So is there a good argument for four? And is making good arguments one of them?

Depending on which source of pop-rationality you consult, there are three, five, six or more ways of thinking that need to be mastered before the psychology-entertainment complex will consider you “smart”. So is there a good argument for four? And is making good arguments one of them?

Well, here one will not learn about syllogisms or the perils of affirming the consequent. The author, a professor of applied mathematics, has instead adapted a classification of natural systems once proposed by the whiz-kid Stephen Wolfram to describe in turn four ways of understanding the world: statistical, interactive, chaotic and complex. Statistics can help uncover broad truths across populations, such as, for example, the basic truths of healthy eating, but headline-grabbing claims can be statistically underpowered and so unreliable, as Sumpter lucidly demonstrates with claims such as that psychological “grit” is a hugely important factor in success. (“Although grit explains around 4% of the variation between individuals,” he notes mildly, “this leaves a further 96% unexplained.”)

More here.

A poetic, panoramic memoir of insomnia

Samantha Harvey in The Guardian:

All our body wants is to sleep, it wants to leave us, head back to the stable, a worn-out horse,” writes Marie Darrieussecq, at which I, a worn-out human, think yes. In a recent interview, Darrieussecq reflected on how much of her work is concerned with inhabiting. Who has a right to inhabit this planet, she asks, and who doesn’t? Though she was talking about her novel Crossed Lines, in which a Parisian woman finds her life becoming bound up with that of a young Nigerian refugee, she could just as well be referring to Sleepless (Pas Dormir in the original French), a book that is – what? A memoir/interrogation/painting/song of insomnia, her own and that of others. It’s a book about where, why, how we sleep and don’t sleep; about how to find a place in the world where sleep can happen, a stable for the worn-out horse.

All our body wants is to sleep, it wants to leave us, head back to the stable, a worn-out horse,” writes Marie Darrieussecq, at which I, a worn-out human, think yes. In a recent interview, Darrieussecq reflected on how much of her work is concerned with inhabiting. Who has a right to inhabit this planet, she asks, and who doesn’t? Though she was talking about her novel Crossed Lines, in which a Parisian woman finds her life becoming bound up with that of a young Nigerian refugee, she could just as well be referring to Sleepless (Pas Dormir in the original French), a book that is – what? A memoir/interrogation/painting/song of insomnia, her own and that of others. It’s a book about where, why, how we sleep and don’t sleep; about how to find a place in the world where sleep can happen, a stable for the worn-out horse.

Sleepless isn’t a book that’s straightforward to convey, at least not briefly.

More here.

Andreas Wagner Pursues the Secrets to Evolutionary Success

Veronique Underwood in Quanta Magazine:

Every organism responds to the world with an intricate cascade of biochemistry. There’s a source of heat here, a faint scent of food there, or the crack of a twig as something moves nearby. Each stimulus can trigger the rise of one set of molecules in an animal’s body and perhaps the fall of others. The effect ramifies, tripping feedback loops and flipping switches, until a bird leaps into the air or a bee alights on a flower. It’s a vision of biology that entranced Andreas Wagner, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Zurich, when he was still a young student.

Every organism responds to the world with an intricate cascade of biochemistry. There’s a source of heat here, a faint scent of food there, or the crack of a twig as something moves nearby. Each stimulus can trigger the rise of one set of molecules in an animal’s body and perhaps the fall of others. The effect ramifies, tripping feedback loops and flipping switches, until a bird leaps into the air or a bee alights on a flower. It’s a vision of biology that entranced Andreas Wagner, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Zurich, when he was still a young student.

“I thought that was much more fascinating than this idea that biology is about counting the number of things that are out there,” he said. “I realized biology could be about fundamental principles of organization in living systems.”

His career, which has included stints at the Santa Fe Institute and the Institute for Advanced Study in Berlin, has taken him from modeling the regulation of gene transcription in an embryo, where precision timing makes the difference between life and death, to asking how an organism can manage to evolve when any change in its genes could spell disaster. He has used theoretical models to probe difficult questions about what drives evolution, and he has wondered about evolutionary innovations that seem to lead nowhere — until they suddenly become the next big thing. His most recent book, Sleeping Beauties: The Mystery of Dormant Innovations in Nature and Culture (Oneworld Publications, 2023), is an exploration of this phenomenon.

More here.

As the hottest summer on record draws to a close, how do we make sense of the images of a climate in crisis?

Alexis Pauline Gumbs in Harper’s Bazaar:

I wanted to write a poem about how the extreme heat of the ocean is breaking my heart, but the whales beat me to it. In late July, almost 100 long-finned pilot whales left the deep, usually cold waters where they live—so deep, so cold that scientists have barely been able to study them. Together they came to the coast of western Australia and huddled into a massive heart shape (if your heart were shaped like 100 black whales, like mine is). Then, collectively, they stranded themselves on the shore. As soon as they lost the support of the water, their chest walls crushed their internal organs. They literally broke their hearts. Choreographed under helicopter cameras.

I wanted to write a poem about how the extreme heat of the ocean is breaking my heart, but the whales beat me to it. In late July, almost 100 long-finned pilot whales left the deep, usually cold waters where they live—so deep, so cold that scientists have barely been able to study them. Together they came to the coast of western Australia and huddled into a massive heart shape (if your heart were shaped like 100 black whales, like mine is). Then, collectively, they stranded themselves on the shore. As soon as they lost the support of the water, their chest walls crushed their internal organs. They literally broke their hearts. Choreographed under helicopter cameras.

I want to write a poem about how capitalism is a sinking ship and how the extreme wealth-hoarding and extractive polluting systems that benefit a few billionaires are destroying our planet and killing us all. But the orcas beat me to it. Off the Iberian coast of Europe, the orcas collaborated and taught each other how to sink the yachts of the superrich. They literally sank the boats. While Twitter cheered.

More here.

The original “Turing Test” paper is unbelievably visionary

Imagining Other Worlds at the India-Pakistan Border

Rashmi Sadana in Sapiens:

There are two main ways to experience the border between India and Pakistan at Wagah: You can cross it through the trade route if you’re a trucker delivering goods or you’ve managed to secure a visa to enter—a difficult if not impossible task for most Indians or Pakistanis. [1] Or, you can attend the daily border ceremony, where soldiers on either side meet to lower their countries’ flags in an elaborate display of military pageantry.

There are two main ways to experience the border between India and Pakistan at Wagah: You can cross it through the trade route if you’re a trucker delivering goods or you’ve managed to secure a visa to enter—a difficult if not impossible task for most Indians or Pakistanis. [1] Or, you can attend the daily border ceremony, where soldiers on either side meet to lower their countries’ flags in an elaborate display of military pageantry.

From the India side, I head to the border ceremony, arriving first at a multilevel concrete parking structure. The anticipation builds as I get out of a taxi and join the droves walking from the parking lot to a football-like stadium.

It’s July 2022, and in a few weeks, both countries will celebrate their 75th anniversaries of independence from British colonial rule.

More here.