by Jochen Szangolies

The simulation argument, most notably associated with the philosopher Nick Bostrom, asserts that given reasonable premises, the world we see around us is very likely not, in fact, the real world, but a simulation run on unfathomably powerful supercomputers. In a nutshell, the argument is that if humanity lives long enough to acquire the powers to perform such simulations, and if there is any interest in doing so at all—both reasonably plausible, given the fact that we’re in effect doing such simulations on the small scale millions of times per day—then the simulated realities greatly outnumber the ‘real’ realities (of which there is only one, barring multiversal shenanigans), and hence, every sentient being should expect their word to be simulated rather than real with overwhelming likelihood.

On the face of it, this idea seems like so many skeptical hypotheses, from Cartesian demons to brains in vats. But these claims occupy a kind of epistemic no man’s land: there may be no way to disprove them, but there is also no particular reason to believe them. One can thus quite rationally remain indifferent regarding them.

But Bostrom’s claim has teeth: if the reasoning is sound, then in fact, we do have compelling reasons to believe it to be true; hence, we ought to either accept it, or find flaw with it. Luckily, I believe that there is indeed good reason to reject the argument. Read more »

According to my father, David Mamet once said that his scripts are about “men in confined space.” I have been unable to verify this quote, but if you look on the internet, there’s an awful lot of writing about Mamet and “confined space.” In particular, I suspect the origin of this apocryphal statement may be

According to my father, David Mamet once said that his scripts are about “men in confined space.” I have been unable to verify this quote, but if you look on the internet, there’s an awful lot of writing about Mamet and “confined space.” In particular, I suspect the origin of this apocryphal statement may be  “Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973.

“Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973. Drug overdose deaths have

Drug overdose deaths have  As an insider observing this food fight, it is surreal to watch reporters and commentators promote the narrative that the government’s Likud-Jewish Power-Religious Zionism coalition and the Supreme Court exist on extreme opposing ends of the political spectrum. Their differences, when it comes to how they rule over the lives of Palestinians, are purely cosmetic. In essence, one camp wants to eat with their hands while the other wants to mandate forks and knives, but in both scenarios, Palestinian rights will be devoured.

As an insider observing this food fight, it is surreal to watch reporters and commentators promote the narrative that the government’s Likud-Jewish Power-Religious Zionism coalition and the Supreme Court exist on extreme opposing ends of the political spectrum. Their differences, when it comes to how they rule over the lives of Palestinians, are purely cosmetic. In essence, one camp wants to eat with their hands while the other wants to mandate forks and knives, but in both scenarios, Palestinian rights will be devoured. On the sunny first day of seminar, I sat at the end of a pair of picnic tables with nervous, excited 17-year-olds. Twelve high-school students had been chosen by the Telluride Association through a rigorous application process—the acceptance rate is reportedly around 3 percent—to spend six weeks together taking a college-level course, all expenses paid.

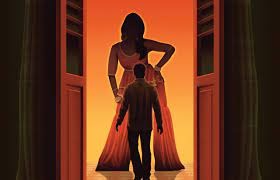

On the sunny first day of seminar, I sat at the end of a pair of picnic tables with nervous, excited 17-year-olds. Twelve high-school students had been chosen by the Telluride Association through a rigorous application process—the acceptance rate is reportedly around 3 percent—to spend six weeks together taking a college-level course, all expenses paid. Trying to sort out who is who, and what everybody wants, is no easy task in “Joyland,” a début feature from the Pakistani director Saim Sadiq. In Lahore, a woman named Nucchi (Sarwat Gilani), who already has three daughters, remarks that her water has broken; she might as well be announcing that dinner is served. For the birth of her fourth child, she is ferried to hospital on the back of a moped driven by Haider (Ali Junejo), whom we take to be her husband. Not so. He is, in fact, the brother of her husband, Saleem (Sameer Sohail). Haider is married to Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq); they have no offspring, to the dismay of his aged father, known as Abba (Salmaan Peerzada). All of the above inhabit one household. It’s not a peaceful place, or an especially happy one, but it’s home.

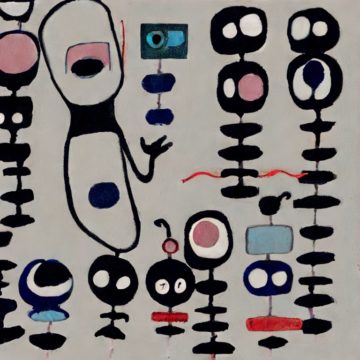

Trying to sort out who is who, and what everybody wants, is no easy task in “Joyland,” a début feature from the Pakistani director Saim Sadiq. In Lahore, a woman named Nucchi (Sarwat Gilani), who already has three daughters, remarks that her water has broken; she might as well be announcing that dinner is served. For the birth of her fourth child, she is ferried to hospital on the back of a moped driven by Haider (Ali Junejo), whom we take to be her husband. Not so. He is, in fact, the brother of her husband, Saleem (Sameer Sohail). Haider is married to Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq); they have no offspring, to the dismay of his aged father, known as Abba (Salmaan Peerzada). All of the above inhabit one household. It’s not a peaceful place, or an especially happy one, but it’s home. “Barbara Kassel”s evocative paintings explore the passage of time. From her loft in New York City, she paints interior and exterior views, creating a visual diary of daily life. Working with oil on panel, the smooth surfaces are meticulously rendered serene scenes. Warm reds and yellow embrace cooler blues and grays and invite the viewer into the large-scale works. Kassel describes the paintings in part biographical and instinctually narrative. Carefully exploring the world around her, she mixes observation and invention as she captures fleeting moments in time.”

“Barbara Kassel”s evocative paintings explore the passage of time. From her loft in New York City, she paints interior and exterior views, creating a visual diary of daily life. Working with oil on panel, the smooth surfaces are meticulously rendered serene scenes. Warm reds and yellow embrace cooler blues and grays and invite the viewer into the large-scale works. Kassel describes the paintings in part biographical and instinctually narrative. Carefully exploring the world around her, she mixes observation and invention as she captures fleeting moments in time.” Jacob Browning and Yann Lecun in Noema:

Jacob Browning and Yann Lecun in Noema: David Van Reybrouk in Noema:

David Van Reybrouk in Noema: Daniel Bessner in Boston Review:

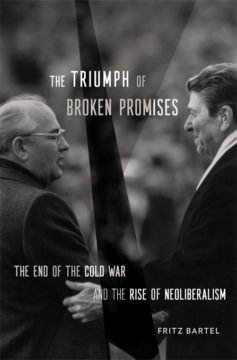

Daniel Bessner in Boston Review: Max Krahé in Phenomenal World:

Max Krahé in Phenomenal World: I

I It’s a testament to Black endurance and brilliance that the little girl called Phillis Wheatley became, within 12 years of her arrival in Boston, the most significant African American poet of the 18th century. Yet, as

It’s a testament to Black endurance and brilliance that the little girl called Phillis Wheatley became, within 12 years of her arrival in Boston, the most significant African American poet of the 18th century. Yet, as