by Derek Neal

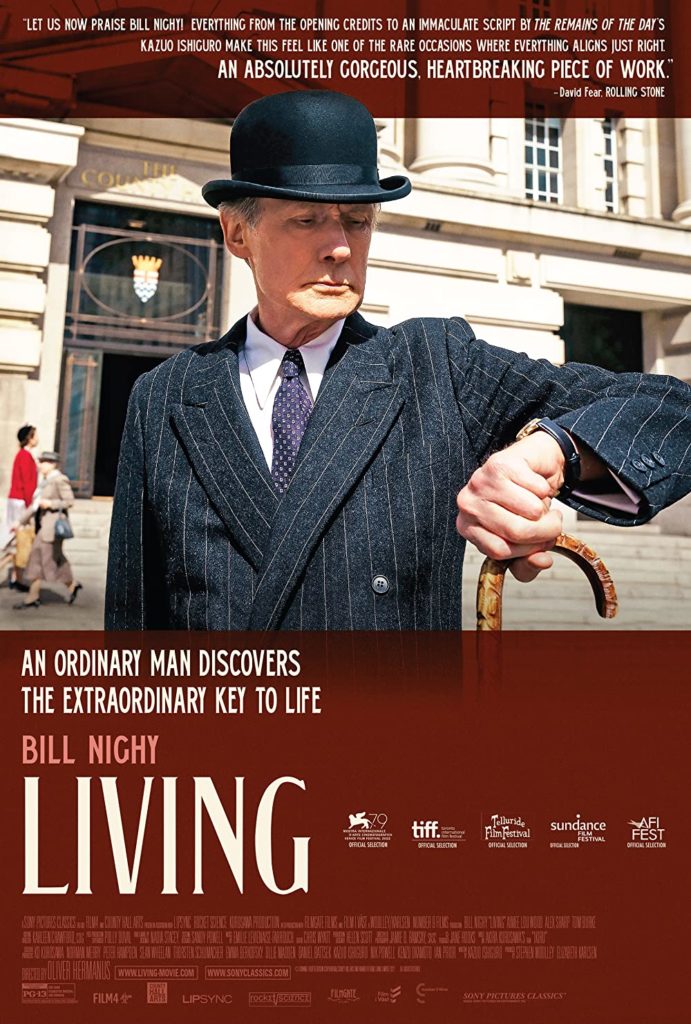

According to my father, David Mamet once said that his scripts are about “men in confined space.” I have been unable to verify this quote, but if you look on the internet, there’s an awful lot of writing about Mamet and “confined space.” In particular, I suspect the origin of this apocryphal statement may be a review of American Buffalo by Roger Ebert, in which he mentions that Mamet’s play succeeds where the film fails because, on stage, the characters are “trapped in space and time,” while on the screen they seem “less confined.” It goes without saying that a film allows for greater movement of its characters than a play, but a movie can trap its characters if it chooses to, and this choice can be all the more effective because it’s a conscious one, not something imposed by circumstances. One film that makes this choice is Living, which I saw this past weekend.

According to my father, David Mamet once said that his scripts are about “men in confined space.” I have been unable to verify this quote, but if you look on the internet, there’s an awful lot of writing about Mamet and “confined space.” In particular, I suspect the origin of this apocryphal statement may be a review of American Buffalo by Roger Ebert, in which he mentions that Mamet’s play succeeds where the film fails because, on stage, the characters are “trapped in space and time,” while on the screen they seem “less confined.” It goes without saying that a film allows for greater movement of its characters than a play, but a movie can trap its characters if it chooses to, and this choice can be all the more effective because it’s a conscious one, not something imposed by circumstances. One film that makes this choice is Living, which I saw this past weekend.

The first scene of the film sees Mr. Wakeling, young and fresh faced, join his new colleagues on the platform of the local train station. They’re heading into London for the day’s work, and they, along with most everyone else on the platform, are dressed in suit, tie, and jacket. It’s 1953. Because it’s Mr. Wakeling’s first day, he’s unsure about what the appropriate etiquette is. He’s not at work yet, and he hasn’t met two of his new colleagues, although he does recognize a third from the interview. Should he go over and introduce himself? Should he avoid them, pretend he hasn’t noticed them standing there? He makes eye contact with the one he recognizes from the interview, who nods almost imperceptibly, granting him permission and entry into their group.

Mr. Wakeling is introduced by this man, Mr. Middleton (no first names in this environment), who we suspect is his boss as he is older than the other colleagues and seems to command more authority. When Mr. Wakeling tries to make small talk as they await the train, Mr. Middleton visibly ignores him and chooses to read his newspaper. A younger colleague, Mr. Rusbridger, has to inform Wakeling that at such an early hour talking is frowned upon, but that he’ll get the hang of things. However, Middleton is not the boss; after the men get on the train, Bill Nighy’s character, Mr. Williams, comes on board, and Wakeling is informed that he’s the man he should strive to impress. Finally, we’ve understood the relations between these people, we think. But not so.

As the camera follows Mr. Williams down the hallway of the London City Council building, he steps aside into the shadows and bows his head as another man approaches, a Sir James, who is above even Mr. Williams in the hierarchy governing workplace relations. The intricate rules concerning social behavior are the first thing we understand when watching the film, which it teaches us by allowing us to see the bureaucratic world of city government through the eyes of one of its new initiates. This appears to us a suffocating world, and once this is established in the film, we follow Mr. Williams’ attempt to live a life with some sort of meaning and fulfillment in the few months he has left following a terminal cancer diagnosis.

The film features two recurring “confined spaces.” The first is the train compartment that Wakeling, Hart, Rusbridger, and Middleton take to and from London each day. They sit facing one another, two on each side, briefcases on the floor, papers in the lap, and bowlers on their heads. There’s no room to move, and it’s dark, too, although light occasionally shines in through the window.

The other confined space is their workplace, which is an exceedingly dark room (the blinds are never raised) featuring a single, massive desk at which they all sit—Mr. Williams at the head, Hart, Rusbridger, Wakeling, and Miss Harris on the sides, and Middleton at the other end. Their view of one another  is obscured by the stacks of paper piled upon the desk—jokingly referred to as “skyscrapers” by Miss Harris, the only person capable of bringing any levity to the environment—which forces them to exist in half-lit silos where they can’t fully see each other, but if someone isn’t working, or appearing to work, it’s noticeable. This is the world that Williams has inhabited his entire adult life—train to office to train—and it’s one that appears meaningless to him once he knows that he will soon die.

is obscured by the stacks of paper piled upon the desk—jokingly referred to as “skyscrapers” by Miss Harris, the only person capable of bringing any levity to the environment—which forces them to exist in half-lit silos where they can’t fully see each other, but if someone isn’t working, or appearing to work, it’s noticeable. This is the world that Williams has inhabited his entire adult life—train to office to train—and it’s one that appears meaningless to him once he knows that he will soon die.

What a movie allows for that a play doesn’t is the ability to contrast a cramped, enclosed space with an open, outside vista. In Living, this happens multiple times. The first is when we see Williams at a seaside restaurant, the screen filled with light and sun shining in from the wall to wall windows. Prior to this, the film is cast in grey tones and shadows—the overcast morning at the train station, the smoke-filled platform, the shadowy half-light of the train compartment and office, and Williams in his sitting room at home, plunged into the darkness of night.

Williams, we learn, has come to this seaside resort to commit suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills, but decides not to  at the last minute. He offers the pills to the only other customer in the restaurant, a screenwriter who he overhears complaining to the waitress about a lack of sleep. When the writer, Mr. Sutherland, learns of Williams’ condition (“I withdrew this cash and came down here…to enjoy myself. To live a little, as you put it. But I realize I don’t know how,” says Williams), he agrees to take him out on the town. A montage of sorts ensues, Williams and Sutherland bar hopping from one increasingly seedy establishment to the next, until they end up at a sort of makeshift circus tent where a woman on stage is performing a striptease. What had begun as fun has become, in its insistence on pleasure and hedonism, just another confined space.

at the last minute. He offers the pills to the only other customer in the restaurant, a screenwriter who he overhears complaining to the waitress about a lack of sleep. When the writer, Mr. Sutherland, learns of Williams’ condition (“I withdrew this cash and came down here…to enjoy myself. To live a little, as you put it. But I realize I don’t know how,” says Williams), he agrees to take him out on the town. A montage of sorts ensues, Williams and Sutherland bar hopping from one increasingly seedy establishment to the next, until they end up at a sort of makeshift circus tent where a woman on stage is performing a striptease. What had begun as fun has become, in its insistence on pleasure and hedonism, just another confined space.

Here’s Ishiguro’s description of the tent from the script: “the tent’s interior feels stifling: sagging canvas ‘ceilings,’ garish lighting, closely packed benches and wooden chairs arranged in rows across the trodden grass floor.” At this point in the film, we watch with slight apprehension as it threatens to become a sort of bucket list paean to “fun,” but of course that’s not the case with an Ishiguro script. The scene concludes: “Sutherland still stares at Williams. He suddenly becomes freshly aware of their surroundings, looks around at it with a kind of terror.” The camera recedes, showing Sutherland and Williams “isolated in their melancholy, like men on a small boat tossed by wild waves.”

After this attempt at “living a little,” Williams tries again when he runs into Miss Harris in the street. Miss Harris is in disbelief that Williams has been skipping work and implores him to return, but he surprises her even more by spontaneously inviting her to lunch at “Fortnum’s,” clearly a place beyond her means and far too extravagant for Mr. Williams’ usual tastes. As they sit down, the ceiling of the café soars above them, and we perceive the couple to be two small figures in a vast expanse of space. The camera highlights this by panning down slowly from the ceiling, further emphasizing the largeness of the room. And here’s the description from Ishiguro’s script: “Sun-filled room within the famous store.” After lunch, Williams and Harris visit an art gallery; we see them descend a staircase as the camera captures them from below, emphasizing the space above their heads and the high ceilings. They then walk together in the park, two small figures on the screen as the camera shoots from a distance, allowing us to see the towering trees above as the screen fills with light.

After this attempt at “living a little,” Williams tries again when he runs into Miss Harris in the street. Miss Harris is in disbelief that Williams has been skipping work and implores him to return, but he surprises her even more by spontaneously inviting her to lunch at “Fortnum’s,” clearly a place beyond her means and far too extravagant for Mr. Williams’ usual tastes. As they sit down, the ceiling of the café soars above them, and we perceive the couple to be two small figures in a vast expanse of space. The camera highlights this by panning down slowly from the ceiling, further emphasizing the largeness of the room. And here’s the description from Ishiguro’s script: “Sun-filled room within the famous store.” After lunch, Williams and Harris visit an art gallery; we see them descend a staircase as the camera captures them from below, emphasizing the space above their heads and the high ceilings. They then walk together in the park, two small figures on the screen as the camera shoots from a distance, allowing us to see the towering trees above as the screen fills with light.

Mr. Williams has left the confined space of the office and train, largely thanks to the company of a woman. This is a key point in the genre of “men in confined space” and the list of movies that I classify under this title in my head: they’re about the codes of masculinity and how men navigate the expectations placed upon them by the society in which they live. Occasionally, women can offer a way out for these men. To contemporary sensibilities, Williams and his male colleagues are restricted by the conservative morality of the 1950’s in expressing themselves or bonding with one another. This is represented visually by the dark office and train compartment, where their interactions are restricted by a highly regimented language and formality. But this also extends to the private sphere.

In one of the most moving scenes of the film, and one that recalls other Ishiguroian moments, we see Williams and his son, Michael, both building up the courage to speak candidly to one another, and both failing. This happens in the aftermath of Williams’ afternoon with Miss Harris, as Michael’s fiancé, Fiona, has heard from an acquaintance that Williams was seen at lunch with Miss Harris. Just as there are rules governing relations among men, so too between men and women, especially an older man in Mr. Williams and a young, unmarried woman in Miss Harris.

In the scene I’m referring to, Mr. Williams is preparing to tell his son that he’s terminally ill. He rehearses before a mirror: “Look here…Look here. There’s something I’d like to share with you both…Bit of a bore, but…Look here. Bit of a bore but…” Meanwhile, Fiona is preparing dinner while Michael sits at the table, reading the paper. Fiona insists that Michael speak to his father, and he agrees to. But when it’s time to eat, nothing can be said. Mr. Williams will never tell his son that he’s going to die, a fact that causes Michael considerable suffering, as he suspects that his father has told Miss Harris, which he has. In fact, the only people Williams is able to tell about his condition are Sutherland and Harris, two people with whom he has no real connection. In this world, even when men want to express themselves, they find it nearly impossible to do so.

The final third of the film presents a response to the question of how one can live a meaningful life in a confined space. The answer is not to break free, but to find purpose within the guidelines governing one’s existence. Just as rules constrain, they also create possibility, if one is willing to accept them. In a clever storytelling move, the last part of the film takes place after Williams’ death, as his colleagues reflect on the train about how Williams returned to work and engineered the construction of a playground, a project that had been fated to die in a skyscraper paper stack before his return and brought before the Council by three concerned women. In the cramped train compartment, the four colleagues—Wakeling, Hart, Rusbridger, and Middleton—sit silently in thought, but little by little they are drawn out as they begin to share anecdotes of how Williams was able to counteract the bureaucracy of their workplace and achieve something worthwhile.

They are clearly moved, but also hesitant to express their emotion in each other’s company—watching the scene, I was reminded of the sort of timid, shy student who has something to say but is afraid of voicing their idea before the class, and the satisfaction that comes when they work up the courage to do so. One after another, each colleague shares a story about an act by Mr. Williams, and what’s striking about each one is how Mr. Williams must break convention in order to make a difference. In Mr. Middleton’s story, about which he says,“I never told you chaps at the time because…well, it rather annoyed me…”, he relates how Williams begged Sir James to reconsider his refusal of the playground project:

Mr. Williams: “Sir James, please excuse me. But I beg you to reconsider. I beg you.”

In disbelief, Mr. Middleton says to the other, “He begged him. He begged him to reconsider.” Mr. Williams, in his quest to achieve something meaningful before his death, must beg—an emasculating act—but the courage it takes to do this so impresses the others—once they understand the act—that he only rises further in their estimation. During this moment of Living, Williams and the others are able to soar.